6 Comments

We are most appreciative of the feedback we’ve received, through the blog and elsewhere, on NIH support of model organism research. In part 1 of this series, we mentioned that we asked two separate groups to analyze NIH applications and awards. In parts 1 and 2 we primarily focused on R01-based data that were curated and analyzed by our Office of Portfolio Analysis. In part 3, we show results from a broader range of research project grant (RPG) data that were prepared and analyzed by our Office of Research Information Systems. This group used an automated thesaurus-based text mining system which delves into not only public data such as project titles, abstracts, public health relevance statements, but also the specific aims contained in RPG applications.

This is the same approach we use in our “Research, Condition, and Disease Category” (or RCDC) reports, available on the NIH RePORT website. We begin with an automated text-mining process which scans each project, and matches it against a custom thesaurus that draws upon many sources of scientific and medical concepts. The result is a project index of weighted terms and concepts which can be used in the next step – categorization.

For the analysis I’m sharing today, NIH scientific information analysts defined new categories representative of six model organisms – Drosophila, C. elegans, zebrafish, Xenopus, yeast, and Arabidopsis – to examine model organism funding in NIH RPGs across fiscal years 2008 through 2015.

Working in teams, these analysts created, reviewed, validated, and verified the scientific relevance of the resulting category definitions. They weighted and adjusted the scientific concepts and terms that make up each definition to show the relative significance of that concept or term in identifying model organism use. They also calibrated matching thresholds to retain true positive matches while removing as many false positives as best as possible. For example, we explicitly sought to exclude cases in which an applicant might cite research involving model organisms, but not plan to use them in his/her proposed projects. For yeast-related applications, our teams focused on model yeast species, and took special efforts to remove projects related to yeast diseases (mycoses).

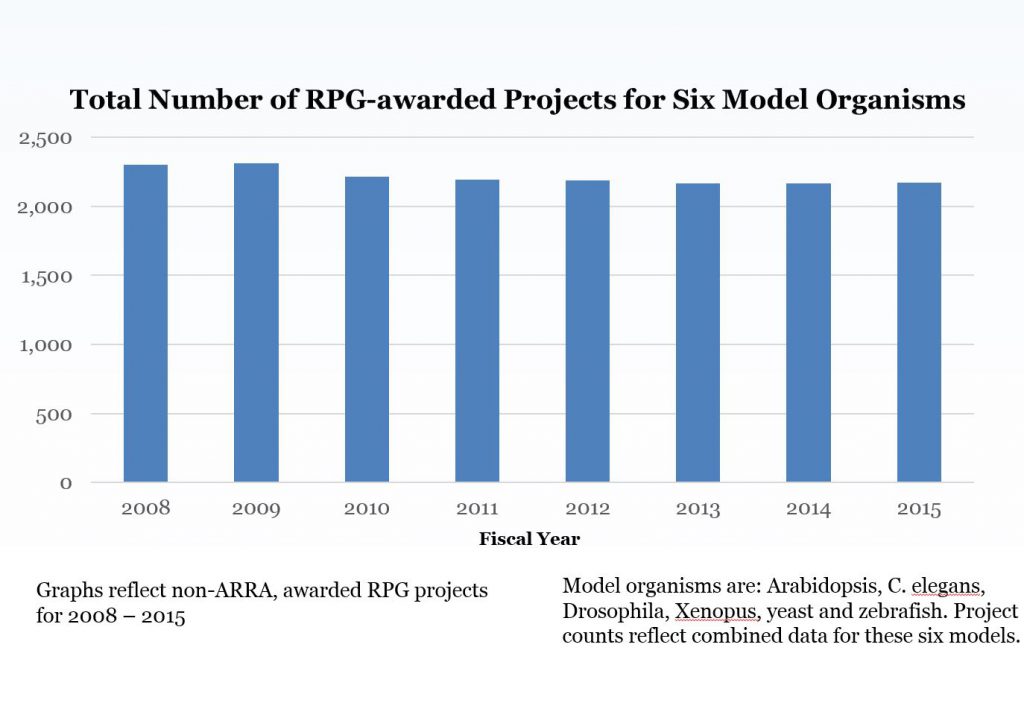

From there, our group then applied these model organism fingerprints to conduct their analysis. Figure 1 shows the number of RPG awards for all six model organisms; if a project included more than one model organism it was only counted once. The number of total model organism RPG projects has remained stable over time.

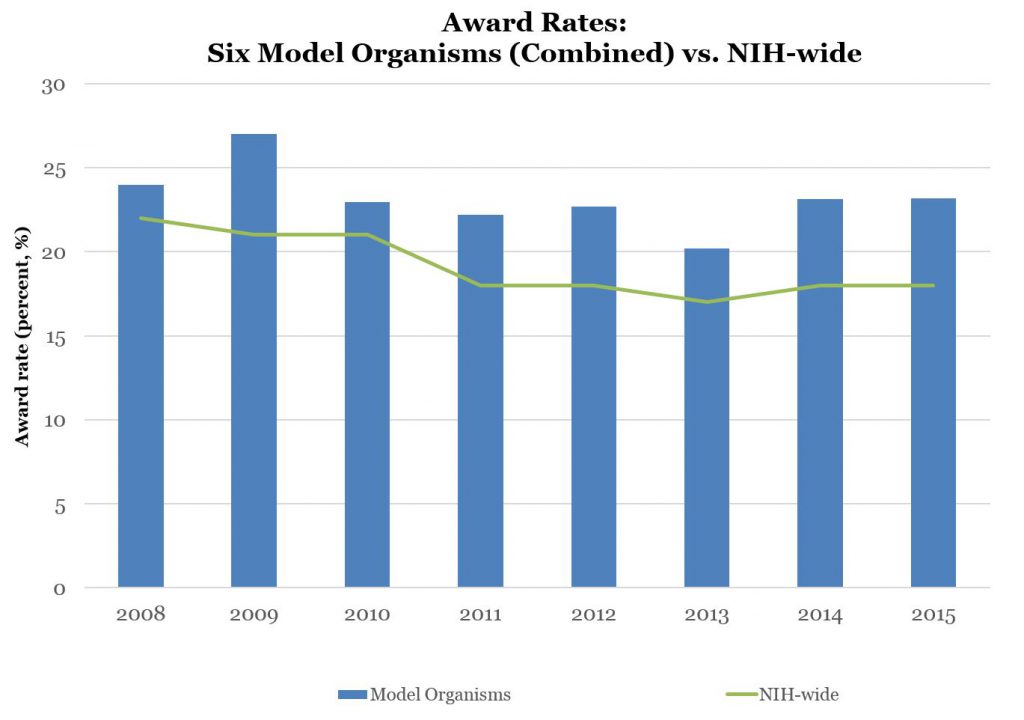

Figure 2 shows award rates – the percentages of applications that were successfully funded if anything, overall award rates for model organism applications are higher than for all NIH applications.

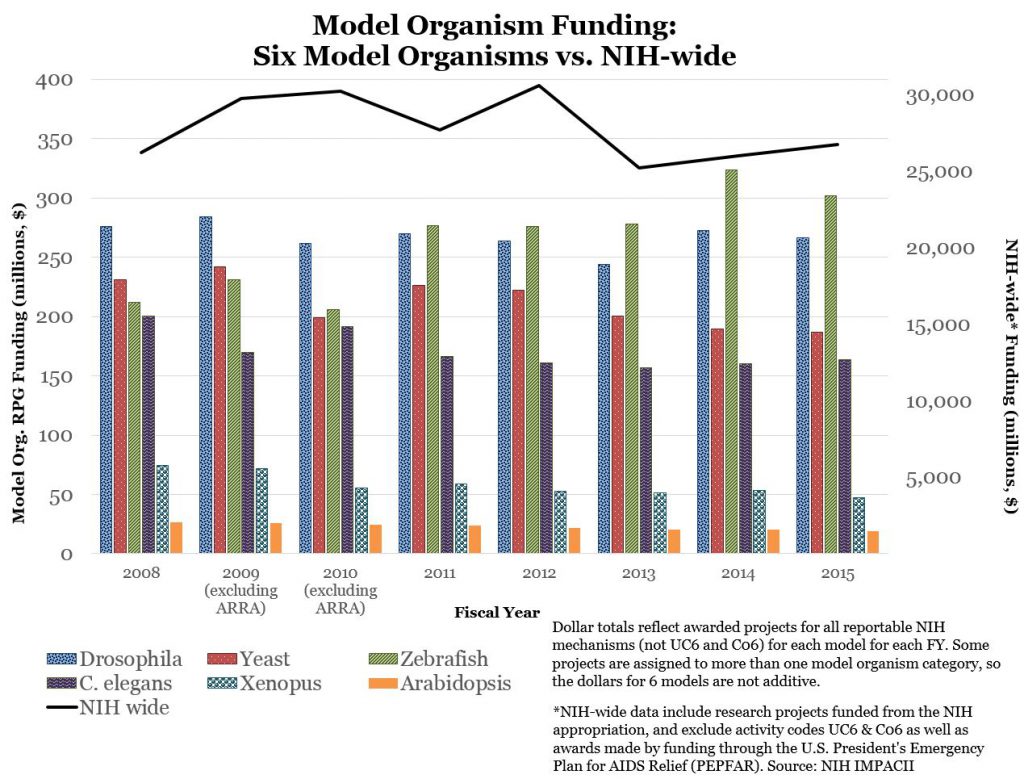

Figure 3 shows funding data for each model organism over time, as well as the comparable NIH-wide funding trend, to put these data into perspective.

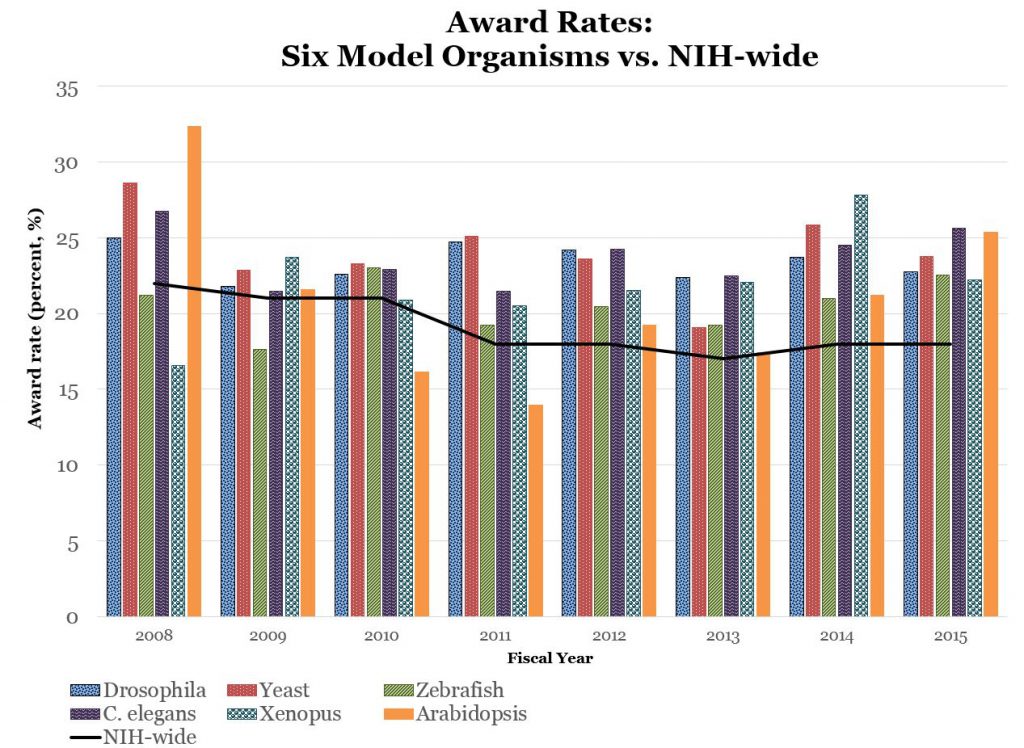

Overall trends are stable – that is reflective of overall NIH RPG funding – though there does appear to be a decline in yeast-model and Xenopus funding, and an increase in zebrafish model funding. However, as shown in Figure 4, over the past few years, award rates for each organism remain at least as high as overall NIH-wide award rates.

These findings, which are based on an automated thesaurus-based text mining system, are consistent with our previously presented findings, and suggest that NIH support for model organism research remains relatively stable with respect to award rates and amount of funding. Shifts in funding among specific model organisms likely reflects changes in the number of applications we received.

Dogs are a much better model for translational studies than any of the organisms listed. What proportion of research using dogs funded by NIH contributes to applications for INDs to the FDA compared to studies using the model organisms listed in your analysis?

I may have missed this, but do you have statistics or are you considering statistics on the following:

1. RO1 or similar awards that are human based research

2. RO1 or similar awards which are truly translational-both human and animals in same proposal?

This is super useful. Thanks. It certainly eliminated a misconception that I (and many of my colleagues) had.

Although we might still grumble that changes happened before 2008 😉

Have you folks at Extramural NIH Research ever heard of the bi-flagellate alga, Chlamydomonas? It is the major model genetic organism for studying the basic cell and

molecular biology of cilia and flagella. Fundamental research on this organism is responsible for our current knowledge of IFT (Intraflagellar Transport) which, in turn, provided the basis

for the role of cilia in PKD (Polycystic Kidney Disease) and many other Ciliopathies.

How about it? And please don’t tell us that there are not enough proposals for statistics!

These studies are helpful, as far as they go. But the history of “biomedical” research demonstrates the value of a broader acceptance of experimental organisms than is implied by the NIH’s short list of anointed organisms — the foci of these statistics. As one who worked for nearly 45 years on a magnificent, experimentally favorable olfactory system in a organism not included on the NIH short list — Manduca sexta — I lament the very poor odds an investigator now faces if s/he proposes work on that or any number of other splendid experimental systems. I was told by my NIH program officer the last time I was striving to get a grant renewal funded (which did eventually happen) that “research on Manduca would not be funded in the future.”

We greatly appreciate all of your suggestions regarding further analyses.