2 Comments

As part of proper stewardship of taxpayer funds, we at NIH are obligated, both legally and ethically, to ensure the welfare and reduce risks for those involved in our supported research activities. This obligation includes research animals. Their humane care and use is something we take very seriously. We appreciate that Congress, the research community, interest groups, and other members of the public look towards us to observe this commitment. Today we are taking some time to touch upon our policies to protect animal welfare, discuss how we process reports of noncompliance, and provide resources to help recipients and researchers ensure their work involving animals is conducted appropriately.

Institutions that receive funds from the Public Health Service (PHS), which includes NIH, must conduct research involving live vertebrate animals in accordance with the PHS Policy on the Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (PHS Policy). The PHS Policy requires all institutions to comply, as applicable, with the Animal Welfare Act and other Federal statutes and regulations relating to animals. Our Animals in NIH Research page discusses relevant policies in more detail and has other resources which may be of interest.

Proper animal welfare means, among other things, appropriate environments, husbandry, veterinary care, and minimization of pain and distress. Proper animal welfare also strengthens the rigor, reproducibility, and translatability of research findings (see also this recent webinar on the ARRIVE guidelines).

When potential animal welfare concerns arise, recipients and researchers are required to promptly report to the NIH Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW), via their Institutional Official and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). We also receive and review allegations from current or former employees, interest groups, the public, other funders, and oversight agencies. More on reporting non-compliance can be found in the section on institutional reporting to OLAW in OLAW’s Topic Index.

The purpose of self-reporting and OLAW oversight is to improve procedures and practices at institutions to ensure animal welfare and ultimately the quality of science. While we understand that an institution may be cautious when sharing compliance information, it shows transparency and a willingness to quickly and effectively correct any issues. When taken together, this goes a long way to strengthening public trust and assures the community that potential animal welfare concerns are evaluated.

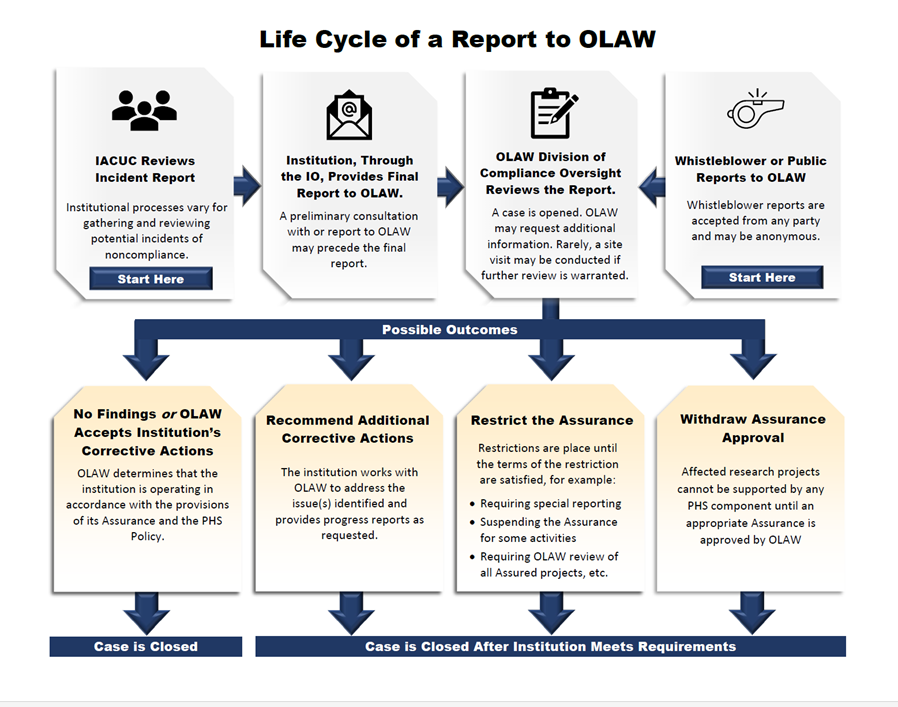

Figure 1. NIH Process for Handling Reports of Potential Noncompliance with the PHS Policy

OLAW uses the PHS Policy and the Guide when evaluating reports. OLAW takes a collaborative and solutions-oriented approach to work with recipients to address animal welfare concerns (see Public Law 99-158). As part of a system of enforced self-regulation, institutions have the flexibility to develop corrective measures that fit their needs, which must then be approved by the IACUC. For serious issues, corrective measures may require immediate attention. If quick corrections are not feasible, interim measures may be necessary. If appropriate efforts are not taken, we can consider restricting or withdrawing an institution’s Assurance or terminating grants. If their Assurance is removed, they can no longer conduct research with PHS funds that involve animals. However, in accordance with the Health Research Extension Act of 1985, institutions are provided “a reasonable opportunity to take corrective action” which is based on realistic timelines developed in response to the infraction. Assurance removal or grant termination would be considered only if no actions are taken by the institution.

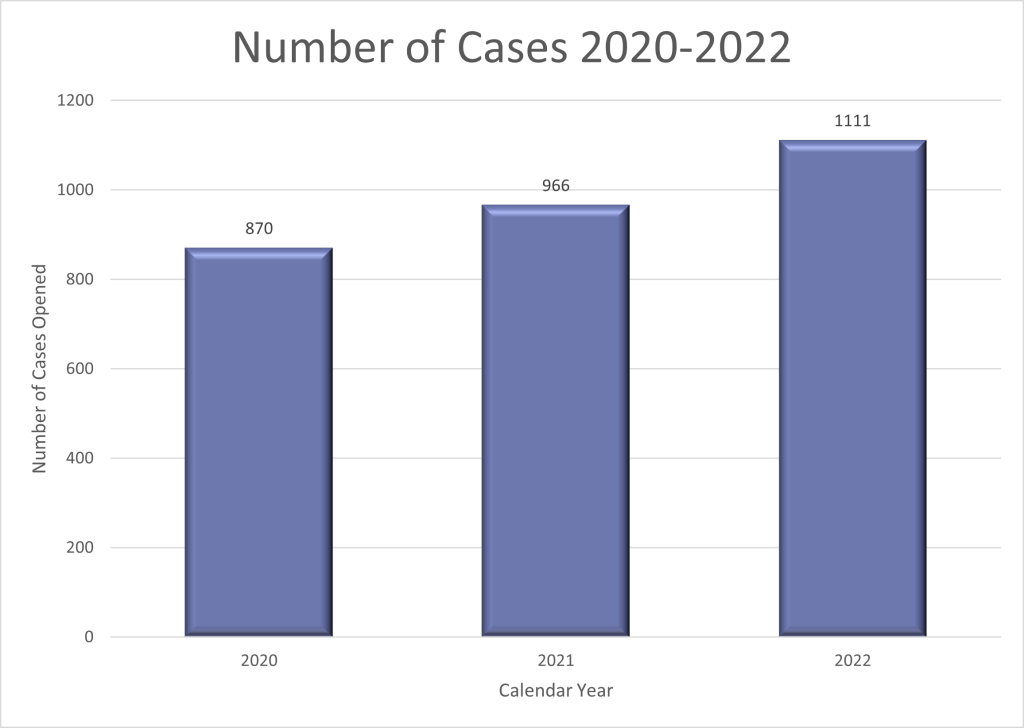

OLAW opened 870 cases of potential non-compliance with the PHS Policy in calendar year (CY) 2020, 966 in 2021, and 1,111 in 2022 (Figure 2). We suspect the increase seen in 2022 (compared to earlier years) was due in part to more research activities ramping up as the effects of pandemic shutdowns lessened. There were also more allegations submitted by interest groups.

Figure 2. OLAW Opened Cases related to Noncompliance with PHS Policy: CYs 2020-2022

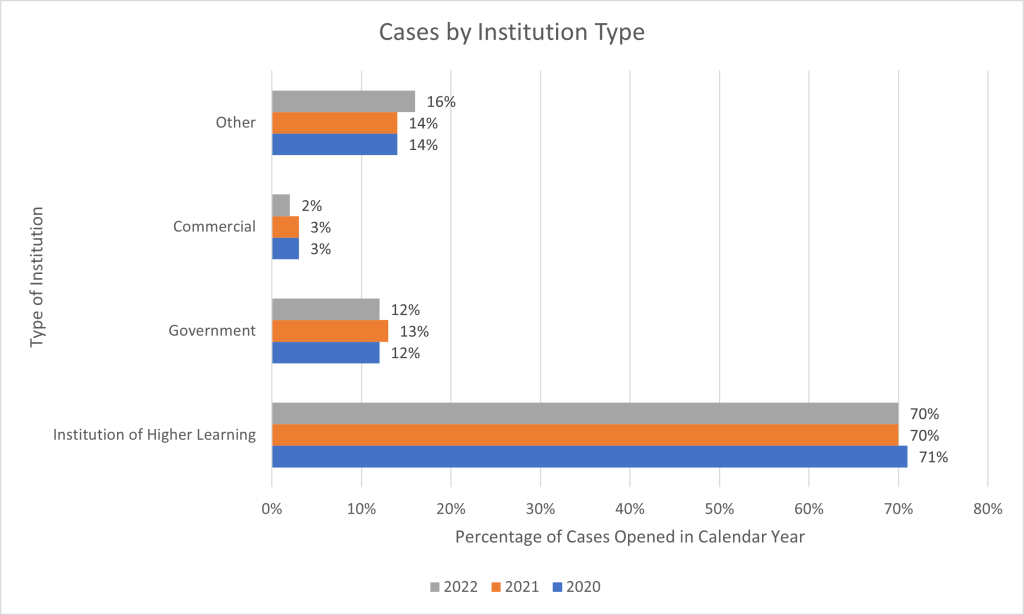

Figure 3 breaks down the types of institutions submitting reports. The majority in CY 2022 come from academic institutions / institutions of higher learning (70% in 2022). Other types of institutions, such as non-profit research organizations and hospitals that are not part of the other categories, made up 16% of reports in 2022. Federal, state, and local government institutions were 12%, while commercial research organizations represented 2%. Similar proportions were seen for CYs 2021 and 2020.

Figure 3. Types of Institutions Submitting Reports: CYs 2020-2022

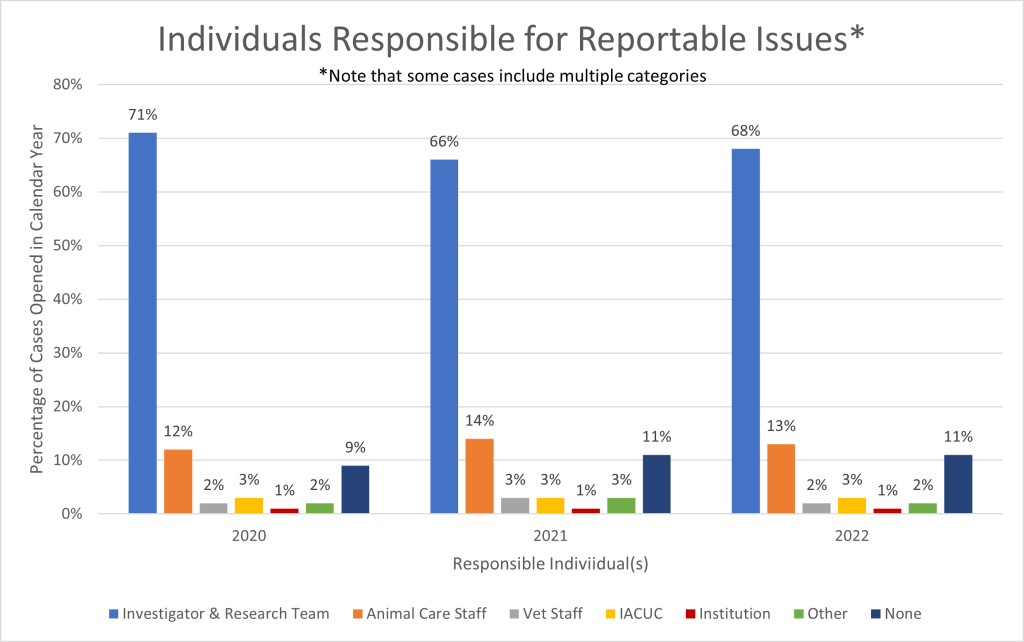

Figure 4 shows that the majority of reportable issues stem from members of the research team (68%) in 2022. Considering this, investigators should ensure all members of the research team are acquainted with approved animal procedures. Reports also came from Animal Care Staff such as vivarium care staff and husbandry technicians (13%), IACUCs (3%), veterinarian staff (2%), other institutional staff (1%), and other functional units such as facility maintenance (2%). Reports referenced in the “None” group include natural disasters and other adverse events involving animal subjects not related to a noncompliance event (11%). The findings were similar for each group in CY 2021 and 2020.

Figure 4. Breakdown of Where Reportable Issues Originate: CYs 2020-2022

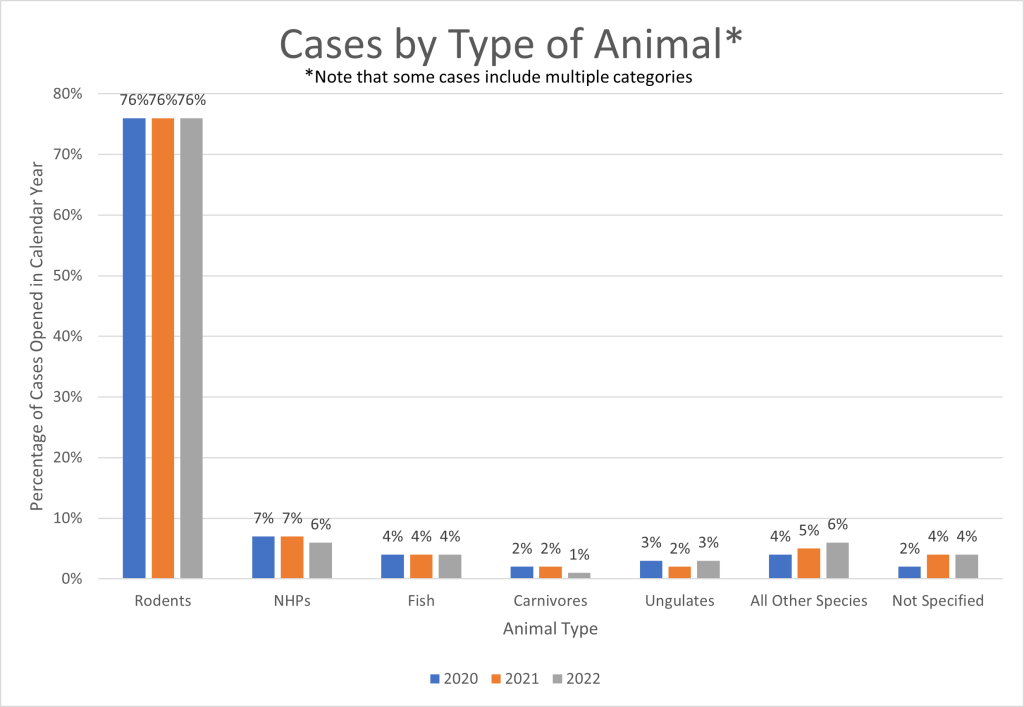

Figure 5 shows a breakdown by the type of animals referenced in the reports. In 2022, rodents were involved in 76% of reports, non-human primates in 6%, fish in 4%, ungulates in 3%, and carnivores such as dogs, cats, and ferrets in 1%. Birds, amphibians, and reptiles are captured in the “other” group at 6%. Animals that were not specified in the reports were in 4%. Similar proportions were seen in CYs 2021 and 2020.

Figure 5. Breakdown of Types of Research Animals Identified in Non-Compliance Allegations: CYs 2020-2022

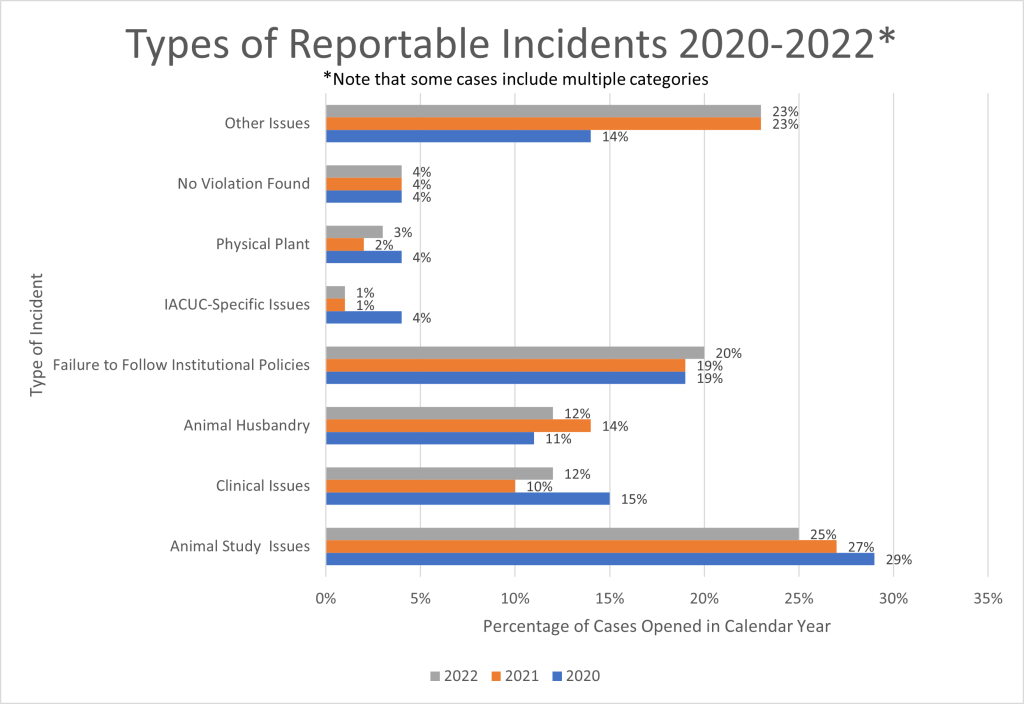

Issues arising during animal studies comprised a quarter of the reportable incidents during 2022 (Figure 6). Examples of such issues are failing to follow study protocols and performing animal activities before receiving approval. Reportable issues also include failing to follow institutional policies (20%) as well as concerns around animal husbandry (12%), clinical veterinary medical issues (12%), the physical plant (3%) and IACUCs (1%). Human error, natural disasters, and other issues made up 23% of reportable cases, and 4% of reported cases actually involved no violation. Similar proportions were seen for CYs 2021 and 2020.

Figure 6. Types of Reportable Incidents OLAW Received in 2022

Though we provide these aggregate data in the spirit of transparency, it should be noted that we do not publicly discuss individual reports of potential non-compliance. Institutions should understand, however, that certain information provided on self-reports may be released as part of a Freedom of Information Act request. Those records may be released if the compliance case is resolved/closed, and appropriate adequate measures have been taken to prevent recurrence. This webinar and podcast explain more about what information may or may not be released if a request is made.

Our goal is to continue ensuring institutional self-reporting in good faith, addressing issues collaboratively, and promptly taking appropriate corrective measures to ensure animal welfare in NIH-supported research. We appreciate the research community’s continued efforts to meet the expectations under the PHS Policy and animal welfare Assurance. If researchers, institutions, or IACUCs have any questions or concerns about these requirements and expectations, please contact OLAW.

Stop all experimental work on innocent, sentient animals! There are more modern ways to do experiments, without using animals! These animal experiments prove nothing, and are not applicable to humans..It is a waste of innocent lives..

More than 90% of all animal testing does not translate to clinical trials in humans. Isuprel, Thalidomide, and Vioxx were tested on animals, but had disastrous consequences in human trials.

LD50 is a toxicology test that is carried out on thousands of Beagles every year. They are fed chemicals, such as weed killers to determine the fatal dose (what kills the Beagle). The EPA requires that LD50 testing be carried out on any new pesticide before it can be listed for sale. There are alternative methods! Disgusting! watch the videos of Beagles being gavaged with poisons. The FDA no longer requires animal testing on new medications.

In 2022, $2.3 million was spent injecting Beagles with cocaine to observe side effects (we already know the side effects). Tax payers money awarded to the NIH goes on to torture your pet Beagle.