38 Comments

Earlier this year, we posted a blog about inequalities in Research Project Grant (RPG) support for extramural principal investigators (PIs). The blog was based on a paper we published in which we showed, among other things, that well-funded PIs not only were supported by more money but also by a larger number of distinct grants. Over 80% of the PIs in the top centile (top 1%) of funding were supported by two or more grants, compared to only 33% of the PIs in the bottom 99%.

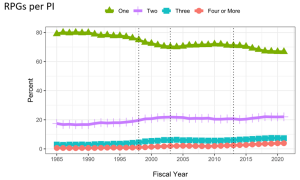

Many comments to that post requested data on time-related trends of number of RPGs supporting individual PIs. Figure 1 shows exactly that. In Fiscal Year 1985, approximately 80% of designated RPG PIs were supported on just 1 RPG (line with triangles at the top); that proportion has fallen over time to 67% in Fiscal Year 2021. Note the vertical dotted lines correspond to the NIH doubling (Fiscal Years 1998-2003) and budget sequestration (Fiscal Year 2013).

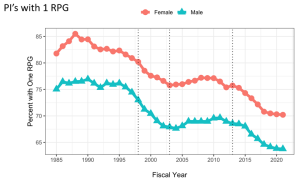

Figure 2 breaks down the same data according to the principal investigator’s self-reported sex. Over time, women were more likely than men to be designated as PI on only 1 RPG.

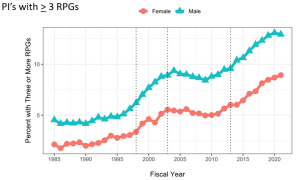

Figure 3 reverses the perspective by showing the proportion of designated PIs supported on 3 or more RPGs. That value has been rising and was always higher for men than for women.

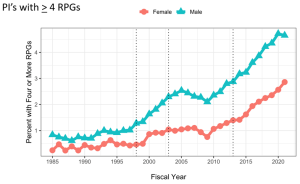

Figure 4 shows the proportion of designated PIs supported by 4 or more RPGs. This rose during the NIH doubling and again after 2009; in Fiscal Year 2021, approximately 4% of RPG PIs were supported by 4 or more RPGs. Men were consistently more represented than women in the group designated on 4 or more RPGs.

We thank you for your interest in our NIH grants data and for your probing questions.

These data are fantastic–thank you for sharing them!

In line with this blog post and the one from June that reported on funding rates by PI–how many applications are submitted per PI per year? I would love to know how funding success correlates with submitting a lot of applications

These data are not surprising, but in some ways disturbing. The biggest concern is the green line declining over the years. While it is most likely that the multi-funded investigators are producing great science, it is self-fulfilling that they have more and more resources making their subsequent applications more data heavy and new, expensive technology heavy. While that is not a bad thing, this limits a different kind of critically important diversity. That is, diversity of thoughts, ideas and approaches. Too many of our peers are disproportionately impressed with novel techniques and low risk (excessive prelim data) and not enough on the potential important questions of translational and clinical relevance. We are losing a lot of great scientists due to lack of funding.

It seems likely than a driver of the decline in PIs with one grant is because institutions increasingly offer little or no support for PI salaries, and instead eliminate Faculty who do not support themselves through extramural funds.

Completely agree.

The soft salary issue is clearly a problem. I agree entirely with Nick. The NIH should consider phasing out paying for PI salaries. This could not be done immediately since so may institutions hired people with this in mind, but it could be slowly implemented for new hires. Institutions could be required to cover 10% of the salary of newly hired PIs, and this percentage could increase 5% a year. Medical schools often provide honorary without salary research professorships to postdocs in large labs so that these individuals can apply for grants, effectively increasing the NIH funding of the labs within which they work. One is not allowed to use independence as a grant review criterion, but if the grants from these individuals were included in the lab heads’ grant numbers, these graphs would likely change significantly. This is less of a problem for GM, but is significant for other institutes.

These comments are more applicable to academic institutions than private research firms who require funding for continued operation. I would, however, offer another suggestion for academic institutions. Like privates, perhaps they need to account for the salary attributed to grant activities? A someone in a private research firm I need to document my hours on a grant — academics should, too, instead of just attributing an arbitrary percentage to “course buyouts”.

Agree. For high-impact publications, you also see the less interesting ideas but tons of testing that only big groups can afford them. The concise papers which have brilliant ideas are often rejected because no in vivo data shown

I have exactly the same impression and interpretation of the data as did David Pollock, and exactly the same concerns with regard to loss of diversity in ideas, approaches, and investigators. With a limited pot from which to draw, when more labs are acquiring multiple large grants the inevitable outcome is a focusing of resources on fewer areas, loss of diversity in the overall portfolio, and loss of talented scientists working in less “sexy” areas who either cannot get or cannot maintain funding and simply give up.

The system feeds on itself. If you have funding, the study section knows your work and is more likely to fund you again. If you don’t have funding from NIH the study section likely does not know your work is unlikely to fund you. Proposals always have weaknesses. The reviewers decide if those weaknesses are disqualifying. That is very often a function of whether they know the person or not.

I agree entirely with David Pollok. We are losing the diversity of ideas. NIH could solve this problem by funding on a sliding scale. All grants that score in the top 50% should receive some proportion of the funding requested. So if a grant scores between 40-50%, it should be awarded at 10% of the budget. If a grant scores 30-40% the PI should get 20% of the budget, and so on.

This is a very interesting idea. Lets do this!!!!

That is a great Idea, particularly for ‘New investigators’ who are really struggling to get their first R01, despite addressing reviewers’ comments/suggestions.

Uneven distribution (high $ amount) and multiple R01s are given to very successful PIs, some times for similar ideas. It would be really appreciated if NIH considers emerging scientists.

One problem with this idea is that for many (perhaps most) proposals, little to no significant work could be done with only a small fraction (e.g. 10-20%) of the requested budget. One example of this is insufficient funding of the personnel required to do the work. I can hire and support a technician by funding their salary 100% off a fully funded grant, or split the support between two grants; but if I could only get 10% support then I’d have a hard time making up the balance. It’s already hard enough when you get a grant funded but then are informed the budget will be cut 15% or 20% across the board.

Good idea in theory but could backfire in practice …

Once my institution takes out 30% of my salary, I would be left with a grant to do nothing but pay my salary (not a policy I’m in favor of, but one I’m stuck with), and no way to renew it because I wouldn’t be able to do the work, and no way to use those ideas for another grant, because they would technically be funded.

Yes, this is it. Exactly.

These comments express very graciously my own thoughts. I would be perhaps more critical to say we have many good, young scientists, as well as seasoned researchers at smaller universities, who struggle to obtain a single RPG. Their struggle is not merely to be noticed for their potential and the importance of their contribution. It is also against a culture that favors 3 and 4 RPG-funded investigators who have far more than they need to do good science. Even a portion of their large budgets would support the new, innovative ideas of the unfunded.

Agreed

Do these numbers also count for PI projects that are within PO1 type grants? Or other similar multi-PI grants where they are officially awarded to one central PI, but in fact support several RO1-like projects within the overall grant?

The analysis focused on principal investigators of research project grants (RPGs), not on project leads of subprojects of multi-component grants (e.g., subprojects of P01 awards).

The increased concentration of research funds in the hands of fewer investigators is indeed disturbing especially when studies have shown that innovation and productivity per dollar decline after a certain point. Unless NIH is willing to set limits on funding R01 equivalent grants, this will continue to the detriment of science.

This won’t happen when the people with multiple awards carry the amount of influence on NIH policy that they do. They won’t allow regulations that limit their funding. It was proposed before and quickly abandoned.

Agreed.

Thank you Dr. Pollock for these comments. Smaller labs with fewer resources and novel ideas are at a disadvantage. These labs still produce excellent science.

It will be also interesting to see the distribution of those multi-project PI. I am guessing many of those were from Institutes such as Harvard, MIT, UC. If you also consider the indirect cost of these institutes (many are >90%) increasing award numbers for these PIs is even more alarming. There should be a more diverse distribution of NIH awards. As it is mentioned by David, these multi-funded investigators have more publications and submit stronger applications subsequently.

I don’t know why we can not put a limit on award numbers per PI and regulate indirect costs at around 50%. NIH really needs policy updates to initiate equitable distribution of research found across every institute/Investigator. I am hoping one day there will be a NIH director with strong determination to solve this problem but there will be too much politics involved especially from those states where most of the NIH funds go.

There may be some grantee institutions with negotiated IDC rates >90%, but Harvard (Medical School) 69%, MIT and Berkeley ~60%, these are pretty typical of top-end R1s.

NIH GMS is leading the way in governing total award per PI that is allowable. Also doing this through their MIRA awards. GM seems to be the most socialist among the institutes in this way.

Worth noting that the trend starts right about 1999, the introduction of the $250K modular budget. 23 years later, if adjusted, that would equate to $440K. So, it seems likely we’re simply seeing an economic reality here: 1) maintain productivity at an ever decreasing relative rate of funding, 2) apply as non-modular and ask for the actual funds needed (though subsequent cut all too likely), or 3) get another grant.

I would be interested in knowing whether there was any difference in lab size between male and females. Might that explain the difference in the number of grants held by males versus females. I currently have one R01 but will need a second in order to support and grow my lab, otherwise my lab has to remain small.

It would be potentially interesting to carry out cross-agency analyses to determine if there are any substantial differences in how federal funding is allocated based around policies for different funding agencies. I am sure that similar data are available for NSF awards to make a comparison and I suspect as well for competitive awards from EPA and DOE as well. DoD operates in a quite different funding model but may have similar data.

I think it’s important to consider all sources of systematic discrimination fueling this inequity, including inequities in resource allocation at the university level. Males are more likely to be in administrative positions at universities. Could male investigators/leaders be better resourced at universities, which makes their grants more competitive to review panels? Further, could male leaders with significant access to administrative resources, lab resources, postdoctoral fellows, and junior faculty, be more likely to network (e.g., on the golf course) and advance the career of male investigators thereby fostering this gender-based inequity? Last, how much time are these male multiple-PI investigators actually contributing to their grants? …and especially considering that many of them have other major commitments to their universities.

I think that NIH could help universities address these issues by discouraging university leaders to apply as PIs on grants. I also think it’s time to revisit a cap on the number of RPGs.

David Pollock’s comment is accurate and insightful, and alternatives like the sliding scale idea should be tried for the sake of intellectual diversity. If the problem is not solved soon, many teacher-scholars are going to become teacher-teachers, and their early new investigator awards will have been for naught. An alternative to the sliding scale approach would be for reviewers to score all RPG proposals as “fund” or “not-fund.” When the “fund” proposals exceed available money, as they will surely do, then a lottery system would be used to make awards among all proposals scored as fundable. That leaves little room for institutional and other biases in the final funding decisions. (This approach is used for distributing the limited school seats in some city’s Gifted and Talented student programs.) First renewal applications could be given some advantage or priority to make sure the original proposal is completed, but second renewal proposals should have no advantage. Universities and institutes would be expected to support their employees in between funding periods.

Current budget limits, as Jeff Mumm pointed out, create incredible barriers to achieving success. For the $250K modular grant to support even one trainee at 100%, the PI can be supported at no more than 50% if they are an Assistant Professor and more likely less than 25% for Associate and Full.

All of the Institutes routinely discourage coming in with $500K budgets (one can of course request more funds beyond that limit, but even then the degree of discouragement is quite high) and a funded grant will typically get a 15-25% cut anyway (usually a combination of reduced direct costs and reduced years). A related concern is the degree to which new investigators get even more resistance from review panels and sometimes within their own institutions when submitting budgets close to the $500K level.

We are also very cognizant of the NIH salary levels, esp for research fellows and adjust accordingly; but we’re not allowed to increase salaries year to year when submitting an application, even though the annual NIH salary increases each year and recently there have been major across the board increases for fellows (well justified levels to be sure). Will NIH be increasing the application limits to take into account the recent significant increases in trainee salaries or begin allowing salary increases after year 1 of a multi-year funded project. All of this is tilting the landscape to less success on a project if one has only one RPG.

NIH may want to consider separate programs for PIs seeking second research grants similar to R01. They can be reviewed separately from typical R01. The program can be something like R21 but with budget close to R01. NO Preliminary Results should be allowed, and the projects should be of high scientific impact (not just solve another typical biological problem). Because no preliminary results are allowed, the review process should be blind so that reputation has a minimal effect on the review of scientific merit. After merit review, open review of PI and environment should be more focused on the likelihood of project success and less focused on reputation and past achievements. NIH should encourage PIs to seek more than one research grants, but the second one should be of much higher scientific merit and impact, and reviews should be more based on the science/idea itself and potential impact rather than other things such as reputation, number of citations, H-index, past achievements. The latter factors should be minimized in the review process because they are determined by funding (at least partially), and funding should not be determined by them.

It is disturbing to see the large PI groups are getting multi grants. NIOH should move to limit the number of grant that can be awarded to a given group. This will be the only way to keep the science innovative and give opportunity for other investigators who do not have large group.

totally agree, and as a ‘side effect’, we see multiple retractions of papers from big names, like recently https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-00202-9 at Dana Farber or previously Stanford’s former president https://retractionwatch.com/2023/12/18/former-stanford-president-retracts-nature-paper-as-another-gets-expression-of-concern/ Those PIs just do not have time to check what their people are doing and produce bad science 🙁

Consider faculty members who teach for 25% versus 50% versus 75% of their time. Consider a researcher at a research institute who teaches for 0% of their time. Do they all “need” or “deserve” equal numbers of grants? Do they all have equal capacities for doing research? To me the answer is fairly obvious that our default expectation should NOT be that everyone should receive the same number of grants.

The gender discrepancy for multiple grants is deeply disturbing.

There’s a big problem with grants (I speak as an NIGMS grantee) being budget-cut to modular or less vs. many institutions’ salary recovery expectations. That combination leaves many single-grant PIs with insufficient funds to actually do and publish what was promised, so PIs have to start side projects to get more preliminary results for additional grants, which distracts from the funded one … in the end, the current system basically traps us in a hopeless Tetris game.

NIH / NIGMS should find a better way to argue with institutions about who should pay PI’s salaries than the current system. I agree that taxpayers should not be paying huge chunks professor salaries at private institutions, but there’s a better way to make the point than slow strangulation of researchers.

I was wondering if the NIH could also examine trends in the number of people with >1 NIH R01 or similar applications who never received an award. This would correspond to the “actively seeking” category used to compile unemployment statistics and would give a fuller picture of the inequality in NIH funding.