66 Comments

As is now well known, black scientists are less successful than their white counterparts in obtaining support from NIH R01 awards as designated Principal Investigators (PIs) (see here and here). Though recent NIH efforts are showing promise to enhance diversity in the biomedical workforce (see this post), much work is still needed to address the funding gap.

In a paper recently published in Science Advances, we delved into the underlying factors associated with this funding gap. We identified three decision points where disparate outcomes arose between white and black researchers: 1) the decision to bring applications to discussion during peer review study section meetings; 2) impact score assignments for those applications brought to discussion; and (3) a previously unstudied factor, topic choice – that is what topic the investigators chose to study.

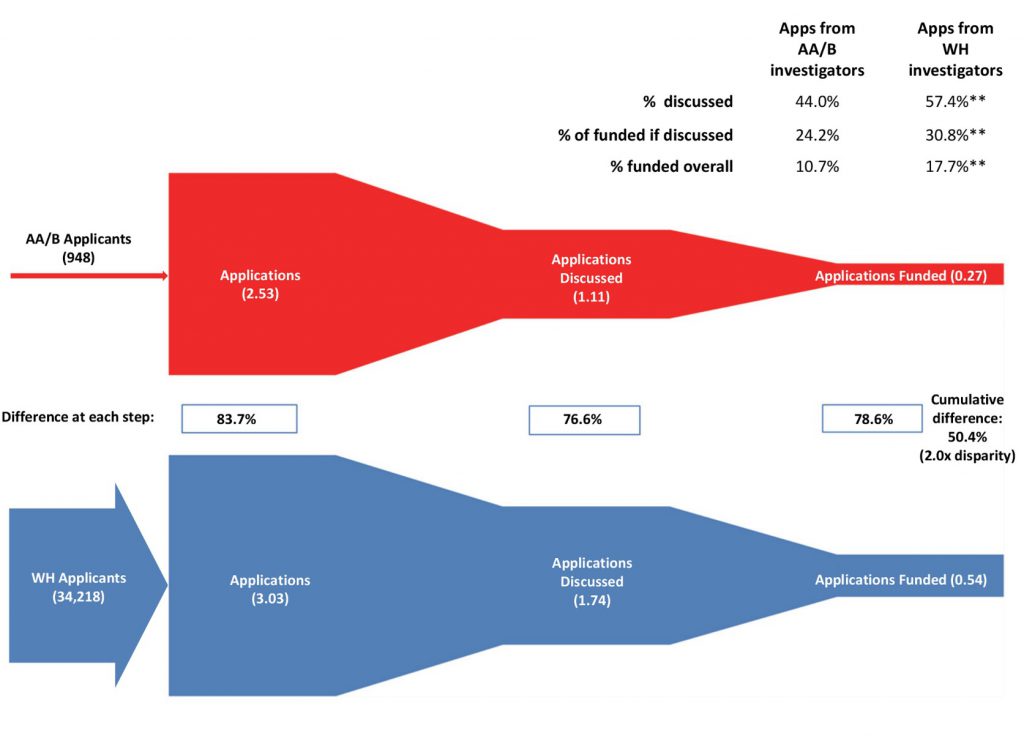

We analyzed 157,549 R01 applications, both new and renewals, from fiscal years 2011-2015. We confirmed previous findings that black researchers submit fewer applications as PIs than white researchers. Applications with black scientists as PIs were brought to discussion in peer review only 77% as frequently as applications from white researcher PI’s (Figure 1).

When applications from black researchers were discussed in study section, they received worse impact scores— 38.4 + 13.4 vs 35.2 + 12.6. Combining lower submission rates, lower discussion rates, and worse impact, black scientists receive R01 funding only half as often as their white peers (Figure 1).

We found a number of differences in the characteristics of applications according to the race of the designated PI. Black scientists were more likely to propose research involving human subjects and less likely to propose work involving animal models.

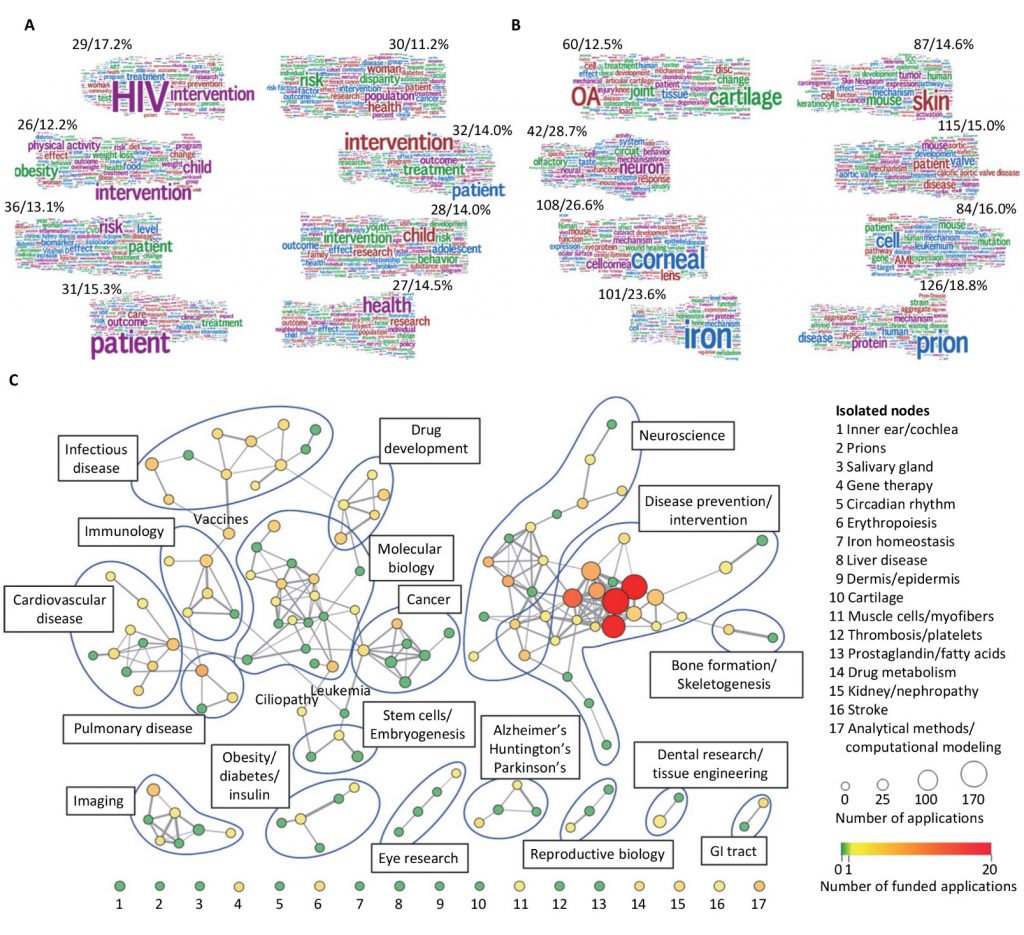

We next used an informatics method called “word2vec” to bin the 157,549 applications into 150 topic clusters, which roughly aligns with the number of standing study sections at NIH. We can describe these clusters by word chains like “retina photoreceptor retinal cone MeSH_Photoreceptor_Cells_Vertebrate rod photoreceptor cells retinal degeneration” or “practice provider clinician care education evidence-based healthcare recommendation medical psychosocial.” Figure 2 shows word clouds associated with the topic clusters with the highest number of applications from black PIs (panel A) and with clusters in which there were no applications from black PIs (panel B). Note that the words in panels A and B are clearly qualitatively different.

A closer look at Figure 2 shows that black applicants were more likely to be associated with topics like health disparities, disease prevention and intervention, socioeconomic factors, healthcare, lifestyle, psychosocial, adolescent, and risk (panels A and C). Generally speaking, applications with these terms were less likely to be funded than topics linked like neuron, corneal, cell, and iron (panel B).

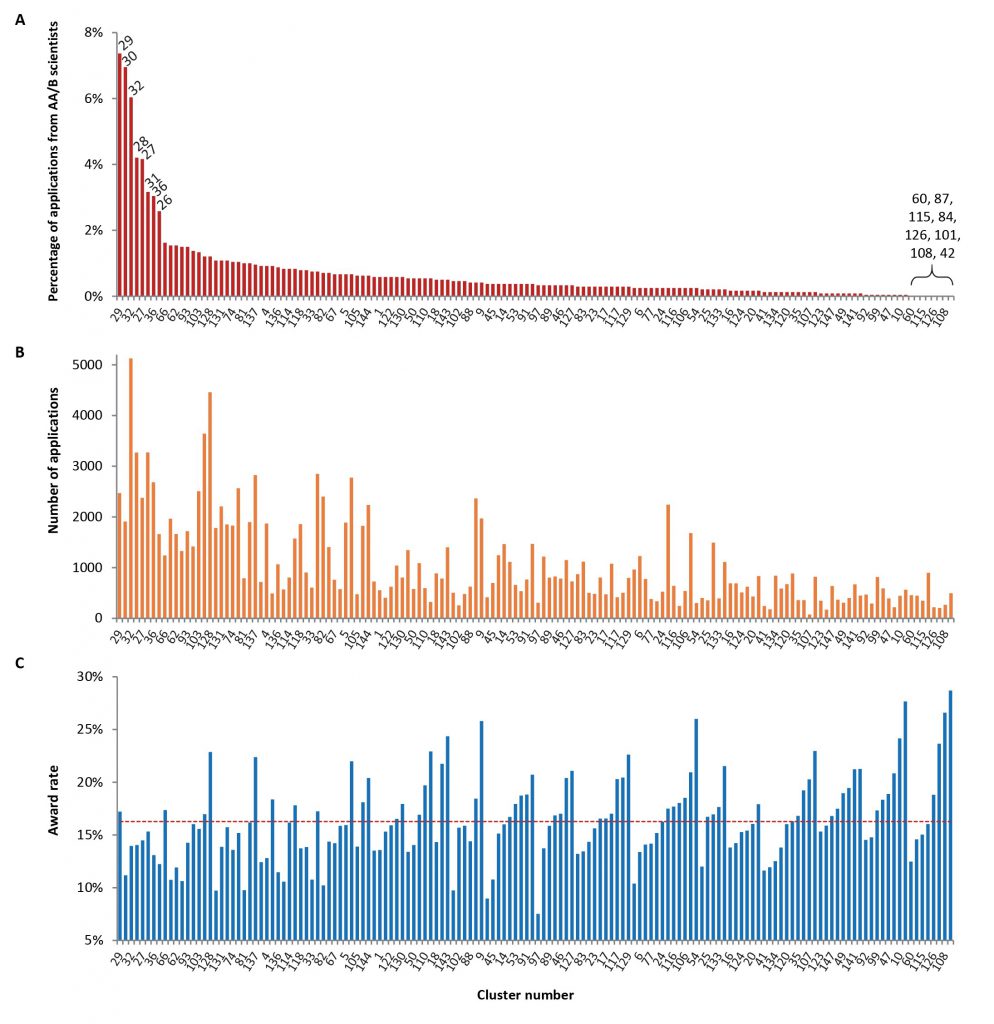

Figure 3 summarizes the word2vec topic cluster data for all applications. Panel A shows the topics in descending order of proportion of applications designating black PIs. Panel B shows the number of applications for each topic (presented in the same order as in panel A). A third of the applications from black scientists mapped to only eight of the 150 topic clusters, which tended to experience lower success rates (panel C). These lower-success topic clusters tended to focus on community and population-level research. Of note, applications from white researchers in these lower-success topic clusters were also less likely to be funded, although not to the same degree as those from black researchers.

We performed a series of multivariable analyses and found that after controlling for variables like applicants’ prior success, topic selection accounted for 21 percent of the funding gap observed between black and white researchers.

We briefly discussed potential implications of our findings – including the need to encourage a more diverse applicant pool, the potential value of mentoring systems to help investigators navigate the NIH system, and the possibility for NIH institutes and centers to consider discretionary funding for topics that may be under-appreciated by review but align with strategic priorities.

The article was indeed thought-provoking and enlightenig with statistically significant powered-analyses of the NIH USA grants-applicants’ pools, primarily Blacks- vs Whites- Americans, endeavoring to address the public health-oriented research with successful target-driven federal grants/budgetary approvals, including extensions and/or renewals!

Future research snapshots would prove beneficial for applicants with enhanced understanding of funding scores, etc.

Indeed, a crisp update.

Hello Dr. Lauer,

Thank you for conducting this important study . One factor that is not mentioned, but implied, is bias of reviewers in the grant review process. Increase in applications from Black researchers will not address this issue. Rather, the ability of those participating in the review to decide which applications “merit” consideration should be closely monitored if not abandoned completely. Likewise, the NIH system of selection of grant reviewers from the pool of funded researchers only serves to perpetuate the exclusion of those who have historically been under-funded. We must find a system that includes all scientists who are active in research and abandon any system that allows individual biais to dominate (i.e., the grant triage process).

Amen

I completely agree that the reviewers themselves have a strong bias towards topics they understand and are within their comfort zone.

This novel concepts are not allowed into the inner circle of already funded investigators

Many meritorious scientists don’t get funded by NIH, irrespective of the melanin content of his/her/their/our skin. Not sure what is meant by “bias” in the comment by Dr. Miller, or why there is an implicit assumption that something needs to be “fixed” in the makeup of committees to address a lower rate of funded black scientists. There are many reasons for this lower rate, as the study showed, and none of them was bias or an intent to “perpetuate the exclusion” of anyone. Maybe more black scientists need to write more grants containing key words that are likely to be funded, such as “neuron, corneal, cell, and iron,” rather than “health disparities, socioeconomic factors, lifestyle, psychosocial.” This speaks to issues of mentorship. The comment that “We must find a system that includes all scientists who are active in research” sounds really great on its surface, but becomes Utopian in practice. In the end, the most impactful research does get funded. The skin color of the PI should never be a consideration in a decision. If I get funded as a black scientist by NIH, it is because my proposal is a great one. It should not be because someone wanted to redress my historically underprivileged status.

Let’s be honest T. Smith, many research institute do not even recruit black researchers. So the pool of black researchers is not only extremely limited, but the subject matters being proposed are not meaningful to the reviewers as you so elegantly put it, “Maybe more black scientists need to write more grants containing key words that are likely to be funded, such as “neuron, corneal, cell, and iron,” rather than “health disparities, socioeconomic factors, lifestyle, psychosocial.” The question is, why do you feel that these subject matters are not relevant when black communities and other communities of color are subjected to health disparities and inequities daily? Perhaps you should assess this from a more holistic way. I mean what is the point of scientific innovations, when the people who need it the most can’t even get access to it because of their zip code or skin color. The research being proposed by black researchers, examine ways to remove those barriers for those communities. Isn’t that just a valuable?

T. Smith may have missed the fundamental focus of the study: Scientist of color are less likely to be funded even after controlling for other relevant factors. I applaud conduct of the study as it adds evidence to a phenomenon that is intuitively known–especially by scientists of color. Politics (i.e., favoritism toward submissions based on personal/professional relationship between reviewers and scientists who submit proposals) is an additional factor that warrants attention. Also, note that the need for research that focus on health disparities, socioeconomic factors, lifestyle, etc. is just as much a priority need (and warranting funding) compared to the topic of animal studies, neurons, corneal, cell, and iron, etc.

Hi T. Smith,

Your comment basically highlights the fact that people’s reaction to this article is shaped by confirmation bias. If you’re skeptical of the notion of systemic racism in science, you’ll notice that they attributed a large amount of the effect to topic choice – a “non-racist” explanation. If you’re sold on systemic racism in science, you’ll take other messages from the paper. I’m not going to outright endorse one or the other position here but I’ll just say that it’s important for people to, on some level, take the authors’ data at face value here.

They are telling us that much of the disparity is due to a single factor – topic choice. I suppose the peril of conducting a “why” study on this topic was that a non-racist explanation would prevail. But if you’re not open to that possibility, you’re not really practicing objective science.

I’ll admit that I haven’t read many other studies on the topic, so that’s something I need to do.

I agree with you.

I agree that the pool from which reviewers are selected further perpetuates this problem.

This is a wonderful first step for Black Scientist. As I was reading the article I noticed in the last paragraph “a potential to encourage a more diverse group.” I would hope since this started out as a study to fill the gap between white and black scientist, this will cater more to black scientist than in other diverse group because when “diverse groups” are added in Black Scientist seems to get lost in the whole ideal and loss out of receiving RO1’s. Maybe at some other point NIH can encourage other diverse groups.

Thank you for conducting this important study . One factor that is not mentioned, but implied, is bias of reviewers in the grant review process. Increase in applications from Black researchers will not address this issue. Rather, the ability of those participating in the review to decide which applications “merit” consideration should be closely monitored if not abandoned completely

Thank you for this delving further to investigate the funding gap between Black and White researchers. It would be important to gain a greater understanding of the potential role of reviewer bias, perhaps by conducting a mixed methods study. Subsequently, developing interventions and/or programs to address this reviewer bias would be an important step.

I agree. It seems much of the problem lies in the reviewing process.

Great and detailed study. It seems that the reasons are complex. Those who want to see analysis of bias need to explain HOW does one assess bias of reviewers. First of all, do reviewers even know the race of the applicant? I have reviewed hundreds of grant proposals in the past, and honestly, while I guess it’s possible to check someone’s race via google search, who the heck has time for that, and why should one do that? In order to be unbiased, reviewers should NOT know the applicant’s race.

The article is clear in that key words re: the focus of the research (e.g. health disparities, socio-economics, etc.) is a pretty good indicator of scientists of color.

This is similar to tenure decisions. A Black professor’s dossier can be identical to a White colleague (or better for that matter). Yet, the former’s documents will be scrutinized to no end. I’ve witnessed this first hand on multiple occasions. The structure of this country is based on/in systematic racism and bias, there’s no way around it. Advance degree attainment will not save you from this wellness depleting depravity. However, if you do a lot of skinning and grinning, you may have a fighting chance.

It is enlightening to see that even when white investigators are proposing topics similar to black investigators, the success disparity remains. That is similar to several experiments of MBA graduates from distinguished institutions seeking jobs on wall street. Given same qualifications the primary driver of applicant success was use of ethnically identifiable vs. main stream names. Scientists are far from different fro the larger US society. Having diverse scholars on the study section and review panel in evaluating applications is among the most important steps the NIH can take to begin to address possibility of systemic bias or even subconscious systematic differences regarding who gets benefit of the doubt in funding decisions, etc. It is too bad, there is no easily implementable double blind review process in place at the moment.

This is a very important study. Will you consider doing similar research with other under represented minority investigators such as Latinos?

Thank you so much for doing this research and finding out more about this topic. It was eye opening and great to know which areas are more likely to be funded. I agree with previous comment that increase in numbers of applicants is not the only solution the solution, but also reviewers need to understand different needs for different populations. Biomarkers are fascinating and amazing, but so is human behavior and hopefully NIH can consider pushing both forward. I go to the hospital and what makes me adhere to treatment is not only how great the treatment is, but also my will to survive and how I feel respected as a human being. I guess that will be some day in the future where we can merge the gap between technology and human connection

Thank you. It is my opinion that the reviewers become biased just by looking at names of the PI . If the team has other common names they selectively give more importance to those coinvestigators , ignoring the PIs ideas & efforts .

It is clearly affecting the minority scientists and those with Asian names especially women with Asian names.

Happens more in SBIR reviewer panels as well. Phase II proposals in particular are reviewed in a biased manner. The program officers are also biased in allowing funding for certain impact scores that are not in the excellent or very good range. Some network or favoritism going on – please investigate the program officers as well who control in an unfair manner the funding decisions.

As a grant applicant with non-Western names and prior education in a third-world country (stated in Biosketch), I found that at least one of three reviewers in each of my grant applications expressed a biased attitude toward me in the Investigator category. Further, some reviewers gave comments about my qualifications as PI that contradicted the fact clearly stated in the application, e.g. the applicant has never been PI. The fact that I shared the lab space and equipment with other PIs in a consortium was taken by one of the reviewers as a Weakness.

I strongly believe that the serious problem in the grant review process is due to the fact that the reviewers can say anything they want in the reviews because 1) the single-blind nature of the review process is used (i.e., the applicants are not allowed to know the reviewers), 2) the review system discourages the applicants to officially file a complaint, and 3) it is likely that NO monitoring system is in place or enforced by the program officers to monitor the performances of the reviewers.

In some ways, this is entirely expected – institutions/companies strive for diversity of people, as long as those people are doing the same thing as everyone else; conversely the point is to really foster diversity of ideas and approaches. This misconception is reinforced by the vicious circle of having reviewers who are looking for (and are comfortable with) the status quo, who thus have little interest in fostering different/diverse ideas. Until there is a deliberate effort to ensure that reviewers are either taken from diverse scientific and ethnic backgrounds or, at worst, there is an explicit insistence that diversity (in its broadest sense) is a part of the review process, these findings are unlikely to change anytime soon.

My view on why Black scientist are not making the already competitive landscape of NIH R01 funding stems from three major issues

1. Poor research support from their institutions which generally provide low dollar value in form of start-ups compared to their white peers. This make it difficult to adequately prepare for cutting edge experiments, publish and fairly compete for R01

2. Because of limited fundings, black scientist, then devise a strategy of overcoming this shortage of funding and less publication by doing population studies which are also less cutting edge.

3. Bias reviewers who may or may not know their inherent biases.

Only 21% of the gap is due to research topic. Increasing the number of applications by black researchers is not the answer. Providing mentoring to black applicants assumes that we are someone incapable and need extra help. There was no discussion of working on the racial biases of the reviewers?

Everyone benefits from mentoring, and it should be encouraged. Your comment “Providing mentoring to black applicants assumes that we are someone incapable and need extra help…” suggests that you do not understand the proper role of a mentor, and how it can be transformative to a career. Mentoring does not equal remediation. In fact, it is the surest way to career success. Thus the K awards that NIH has sponsored for a long time, in which mentorship is a critical component. Before casting aspersions on NIH reviewers or assuming that they are all biased, do you have any data to show that that NIH committees are less than diverse in race, sex, or another useful metric? Or that there is a racial bias anywhere except in your own imagination?

This was a well conducted and important study. To me, the results imply that there really needs to be “implicit bias training” for NIH reviewers. Maybe if it were done as a simple, quick, and fun online quiz or other exercise that would show each reviewer their implicit biases before they accessed the grant applications. As a long time NIH peer reviewer, I’ve seen plenty of bias, but I think its usually unintentional and implicit.

Not sure about you, but I have enough mandatory online training…no, no, no…please do not add another useless training (draining) exercise which will sap people’s time and energy. There is no evidence that this is needed, or that it would solve your proposed problem.

Explaining 21% of funding gap still leaves 79% un-explained gap. The reality is that NIH reviewers are reflection of the overall society. Imagine if a retailer tells shoppers that payments for merchandise are honor based and there will be no consequence for non-payment. That retailer will go out of business in a pretty short order. NIH reviewers has no accountability for being truthful even at most basic levels. I have seen reviewers commit scientific fraud to kill applications and get away with it. NIH has no workable mechanism to address reviewers’ misconduct unless it resulted in undeserved funding in a very flagrant way. 90% of proposal are not funded and by definition 90% of reviewers’ fraud goes into preventing the likelihood of funding. This is where bias against applicants with African-American sounding names and even more so against the Islamic sounding names shows its ugly face. Without reforming the peer review system and formulating proper dis-incentives for reviewer misconduct you will just be applying a band-aid.

I don’t think that a “Muslim sounding name” or “African American sounding name” is a factor in any NIH funding decision. I have a “Muslim sounding name” and I’m black. I’ve not personally had any issues with NIH funding. On the other hand, it is likely that there is an implicit psychological bias and defensiveness on the part of some unfunded researchers. It is easy to rationalize failure by blaming others. An alternative is to take a hard look at oneself and benefit from feedback and constructive criticism.

There may also be an institutional issue. Historically AA/B institutions may not have the necessary infrastructure and scientific expertise to support cell/molecular biology research especially for young investigators.

I think that the key element here is the preference for proposals that study animal models over those that study human subjects. There is no doubt in my mind, speaking as an experienced Immunology reviewer over 15 years, that Study Sections very much prefer the mechanistic proposals that come from animal (or invertebrate) models. I have never perceived racial bias in any of the study sections I’ve participated in, but I have perceived a profound “anti-human subjects research” one.

As the evaluators have no knowledge of race this is a fine example that all racial disparity is not due to racism. It would be less divisive to look at unfunded vs funded applications and we should strive to enable all those that are weak at selecting topics of interest to funding agents and submitting grants to improve and excel without regard to race. A look at institutional support for grant development and mentoring might also be a fruitful area to detect differences. I have witnessed great difference based on leadership of the the Vice Chancellor for research at my institution in the approach, level of support and ultimately success under the various leaders. Sad reality is there is overcapacity for research in relation to funding opportunities and that is a serious flaw in our system as it introduces inefficiency.

I agree with you.

This study is an excellent first step in providing NIH funding for a more diverse set of PIs. I hope that the NIH will consider analyzing this data to identify other factors associated with bias. Because the Biosketch provides indirect but clear evidence of age, those younger reviewers who believe that young investigators are being prevented from obtaining funding because senior investigators are using up the resources tend to give worse scores to PIs who are more senior. This tendency could be offset by (1)encouraging more senior investigators to volunteer for grant review; (2) having a policy of matching reviewer and PI on the basis of not only their knowledge base but their age. Next, a critical examination of the flawed study that suggested that NIH needs to give a “handicap” to young investigators needs to take place. That study wrongly suggested that without such a handicap there would be no new generation of researchers. Let’s have a level playing field as we once had. As a young investigator, I and many of my colleagues teamed up with senior experienced investigators to improve our chances of getting a fundable score. This method provides continuity across generations of researchers and allows everyone to win.

Finally, in an effort to save money and keep reviewers in DC only one night instead of two as was originally done, there is a rush to get half of the applications in the “Not Discussed” category. This is quite unfair, especially to those for whom bias may be more likely to creep in due to being non-white, older, female, or having a creative idea that is outside of the mainstream of topics. Bias also is present if an application is not discussed the first time and is resubmitted. Reviewers being pressured to find the magical 50% for non-discussion tend to seize on those that had previously not been discussed and recommend those for a second time to not be discussed.

I have been a reviewer and recipient of funding for decades and have witnessed all of the biases outlined above. I hope that NIH will at some point convene a panel of experienced reviewers like myself to help them reduce the current biases that is so evident to me.

I’m a NIH funded researcher and like you, I’ve served on NIH review panels. I strenuously disagree with many of the unsubstantiated presumptions of racial bias which I’ve read on this blog, and find many of them misguided. They don’t follow from the study. I’ve never considered the race of an applicant in making a funding recommendation, only the strength of the application and my dispassionate assessment of its impact, based on my subject matter expertise. Moreover, the committees I’ve sat on have been representative of society in general in terms of race, sex, and age. Regarding “ageism,” contrary to your comment, I think that historically much of the negative effect of “ageism” has been directed against young investigators, and this problem was addressed with slightly different rules for first time investigators. Perhaps there need to be more expanded programs for outstanding older investigators. For example, more R37 MERIT Awards and other late-stage career mechanisms could be budgeted, so that experienced investigators can focus on their successful programs without interruption. But in general, I think that most of the effort to make funding accommodations should be on early and mid-stage investigators, who face unique challenges.

I wonder what is meant by the term “Black” in describing researchers. What proportion would be researchers who recently immigrated to the U.S. and those who are descendants of African slaves? Giving more opportunities to people who did not experience discrimination for most of their formative lives does not alleviate the persistent exclusion of Black Americans. It would be useful to see if there is also a gap between Black Americans and Black immigrants.

As a black immigrant myself Sue, I can reassure you that black immigrants (not just African Americans) have experienced discrimination, exclusion, bondage, and lack of access as well. African Americans are not the only group of blacks who have been and continue to be marginalized. I think the research community needs to be careful about not doing more harm than good by not causing further ruptures within the black communities in your proposed quest to understand the differences among them.

Thanks for replying to my comment, Lydje. Are you talking about discrimination in the U.S. or in native countries. My point is that migrants to the U.S. were raised with people who look like them in positions of political power. Skin color would probably not be the basis of discrimination in the native land. I know there are types of discrimination in every country. I also know that all Blacks, Hispanics and Native Americans are treated with high degrees of discrimination and violence, regardless of country of origin. However, in the Academy hiring in many disciplines favors immigrants rather than American-born Blacks, particularly descendants of African slaves. If scholars are hired without racial discrimination, I believe that might be room for all. Right now, that is not the reality.

Are you saying that immigrants “who are descendants of slaves” are less likely to be the focus of discrimination in comparison to American born descendants of slaves?

To what extent do NIH training programs align with Panel A vs. Panel B, and is the issue potentially emerging earlier in the academic research pipeline (ie. training opportunities)?

I think the bias is more structural than racial. It’s really a disciplinary bias. The current NIH system favors basic science with no regard for practical applications over research that applies what we already know to address the health crisis facing our country in general and health disparities in particular. I am not surprised that many black researchers want to tackle pressing community problems. As an African American who came up through the academic ranks at predominately White research one institutions … and has the scars to prove it, I can understand why someone growing up among people who have been systematically discriminated against may be motivated to become a scientist because of a desire to address those problems. I’m not saying that doesn’t motivate white scientists, too. But I’ve seen this motivation toward applied action research in many of my students. Students pursuing such a path within academia may wind up “getting mentored out” of taking that approach. They are told community engaged research not the way to build their career. Rather than change the system, there are those who will advocate for changing the mentoring advice. Thus, the disparity cycle continues.

I completely agree with you. That’s why “the possibility for NIH institutes and centers to consider discretionary funding for topics that may be under-appreciated by review but align with strategic priorities” is this article’s most practical suggestion. As demonstrated by the various posts on implicit bias and the review process, anti-bias training is unlikely to be completely effective by itself, although I happen to think that it would be a good step for both reviewers and NIH leadership. Teaching people to recognize their biases, where they come from, and how to minimize their impact could be especially helpful if it was focused on a wide range of biases, including those based on identity characteristics, pedigree, current institution, and what has been traditionally defined as “cutting edge” or “prestigious” science. If NIH is serious about reducing these funding disparities, it needs to make sure that there are incentives for conducting a wide variety of types of research and that those who set funding priorities and make funding decisions come from a variety of backgrounds and perspectives.

Thank you, Dr. Lauer, for the post and many thanks to Dr. Hoppe and team (Science Advances, 2019) for bringing focus to this funding issue. An earlier respondent suggested more black scientists engage in laboratory or mechanistic research in order to get funded. At best, this solution is a placing a bandaid on a severed artery; at worst, this solution ignores the body of evidence regarding social determinants of health. The last thing we need is to discourage a diverse group of investigators from such study topics.

I have noticed that K award instructions require candidates to articulate how their mentoring team is diverse. Unfortunately, diversity in the mentorship team is not actually part of the K scoring criteria.

A good first start for NIH would be to include diversity as a scoring consideration for mentorship teams (in fellowships and K awards). This solution could lead to benefits such as increased: support for the training of scientists from underrepresented backgrounds, number of women and minorities in scientific leadership positions, and likelihood that scientific agendas highly relevant to underserved groups will be justly represented in the NIH scientific portfolio.

I served as a Division Director at the Center for Scientific Review at NIH from 2009 to 2015, and I can provide some answers to some of these questions, and perhaps some clarification of this issue. From the time of the initial publication of the 2011 Ginther et paper, the NIH began taking several steps toward understanding the causes and finding ways to remedy this issue. A number of committees given access to detailed data were formed (one of which I served on), and a number of findings came from this. The very first hypothesis put forward was the issue of reviewer conscious or unconscious bias, so the idea that this was not considered is inaccurate. While Ginther et all found a small discrepancy in Asian award frequency, further analysis showed that only those identifying as Black/African American had the high, unexplained level of funding disparity compared to White applicants. No such effect was seen for Latinos, or other identifiable groups (including women, who actually showed a slightly higher non significant funding rate compared to men). The bias explanation had a number of problems in that applicant race is not available to reviewers, unless someone on the panel happens to know the applicant’s race. This can happen, but the frequency is unknown. In the hundreds of study section meetings I attended over 18 rounds of review, I have never heard any mention of an applicant’s race. Any comment by a reviewer during any such meeting that had any hint of bias, would result in immediate suspension of the review, removal of the reviewer from the meeting and the study section, and re-review of the application in the next round, according to CSR rules of review. None of this rules out the possibility of unconscious bias, which NIH leadership has taken very seriously. As for the meaning of “Black”, all individuals, whether applicants or reviewers who are involved in the NIH grant process, are given the choice of self identification in one of the racial and ethnic categories provided to all government agencies. Individuals may also choose not to select any identification. There is some anecdotal evidence (from SRO’s who manage study sections) that many African Americans choose not to identify as such. All the statistical data used in analyses makes use of the self identification data, since there is no other objective definition of “race”. This does not mean that the results obtained are less than rigorous, since there is no reason to believe that those African Americans who choose not to self identify have a different grant review outcome than those who do. However the answer to the question as to whether African (or Caribbean) immigrants are distinguishable from African Americans is no. The article cited in this post by Mike Lauer goes some way to providing one rational answer to the reasons for the fairly shocking fact of racial disparity in funding. Other reasons will probably eventually come from further in depth analyses. As a retiree, I do not speak for NIH or CSR, but I am pretty sure that the policies in place 4 years ago to get to the bottom of this issue, not to exclude any possibility, including bias, and make whatever changes can be done to remedy the situation, are still in effect.

The most novel and important research with the greatest impact on patients and public health is often different from the most fundable research. Looking at Figure 2, it honors African American scientists that they focus a lot on clinical treatment, disease risk factors and prevention, public health interventions, child health, infectious diseases, cancer and obesity. Rather than redirecting scientists to more fundable research areas, maybe funds could be redirected to these critically important topics.

NIH should consider improving the diversity of the peer review groups to eliminate inequities and bias. Until people of color are sitting at the table and play a role in the decision making process, these inequities will persist, and the peer review process (a system of oppression) will continue to have hidden racism embedded in it; as the predominantly white reviewers are both biases and do not relate to topics that might be significant to black researchers and the communities they work in. Thank you for showing some light onto this most important matter Dr. Lauer.

Hi there, Dr Lahens. I have sat on Study Sections for many years. I can assure you that NIH does go to extraordinary lengths to ensure that representatives of all communities in the US sit on panels. That would be men and women, and people of Caucasian, African, Hispanic, Asian and other populations are all represented on a routine basis.

I would like to see a table of study section compositions, because at least the ones where I have sat in where predominantly male and white. Is information of racial/gender makeup for study sections available or reported?

From the article, AA applicants tend to choose topics that are less likely to get funded. The solutions proposed by Dr. Lauer are: 1) develop a more diverse applicant pool, 2) Mentoring systems to help investigators navigate the NIH system, and 3) NIH institutes and centers to consider discretionary funding for topics that may be under-appreciated by review but align with strategic priorities. None of these “solutions” address the underlying issue, hence the article after presenting nice data ends with nothing more than a whimper. Where the real push should be is to help AA applicants to do more basic science that study sections are more likely to find sexy and in turn, more likely to receive a fundable score.

We are now 8 years, and approximately 24 Council rounds, past the publication of the original Ginther study in August of 2011. This recent analysis by Hoppe et al. is more of the same vein- no matter which co-variate anyone chooses to blame, the disparity still remains. That’s why your unfortunately subvocalized admission that white PIs who study the same “wrong topics” have better success is so key here. It is beyond disappointing that the title and abstract of the Hoppe article, and the top level messaging/PR on this, pushes “wrong topic” and not “disparity no matter what the topic happens to be” as the take away. This goes along with the “pipeline” response to Ginther, and Director Collins’ quote in a press release that “We need to understand whether there is an intrinsic bias against such topics by reviewers, or whether the the methodologies used in those fields of research need an upgrade”, to show that the official NIH position is that Black applicants deserve their fate. That it is their lack of merit, not any sort of fault of how NIH selects grants for funding, that is the real problem. You see, if we can just find the right Black applicants and train them better (in majoritarian-led labs, of course), to use the right methodologies, to study the proper topics, then all will be well. This is the logic.

This issue of funding disparity is very likely not to have one obvious cause that can be fixed once it is identified. The situation is very clearly, as described in this post by Figure 1, one of death by a thousand cuts. There are many factors which contribute. While reductionism is an understandable attitude for the science community, it is overwhelmingly clear that the approach NIH has taken, i.e., to find one single cause for the disparity that they can point to, is flawed. Hot denials of ever seeing any overtly racist behavior during review, and even half-hearted attempts to address implicit bias on the part of reviewers, are a distraction- these grant award outcomes are far too subtle and multi-factorial for that.

There is one solution that has a chance of making change. The NIH uses grant pickups to address all sorts of disparities. ESI policy is one clear example and yet I do not recall any of this “we need more study” or “the solution is to load the pipeline up with better ESI investigators” or “I’ve never seen bias in review so it can’t be so” or “they need mentoring to study the right topics” or anything of the like. Director Zerhouni just stated baldly that he wanted affirmative action procedures to equalize the success of ESI applicants and it was made so. There are many features of the success data for women PIs versus men PIs that suggest there is still some selective adjustment going on there to fix biases and disparities identified several decades ago.

There are relatively few Black PIs submitting applications and being awarded- on the order of single digit percentages, correct? The number of grant saves that would be required to equalize success rates is very small. There are grants being selected out of order for various reasons all over the NIH on a round by round basis. Yet this one particular aspect of funding disparity somehow does not receive the top-down fixes that other NIH priorities enjoy. It should receive such fixes, immediately.

The longer term impact is anticipated by the comment above which notes that the peer review process is inherently a conservative one. Those who have been successful do the selecting of the next successful PIs. If less mechanistic topics are to fare well, then lots of people who value such topics need to be on study section. Program needs to prioritize selection of such topics, yes, but it all starts with the voted scores. People get on study section, and are influential, when they have vigorous, funded research programs. People have more time to contribute to NIH service when their grants do not face triage more frequently (as per Hoppe), or do not have to be revised more frequently to get funded (as per Ginther). People are more likely to stay in the career, and be available for study section, when they are funded as easily as anyone else. People are more likely to publish science that is of assistance to improving the health and well being of the US population, when they are funded as easily as anyone else.

It is a mystery to me why, eight years after Ginther, the NIH still refuses to use the tools that are available to them to address this one specific aspect of grant award bias and disparity.

Well put, Mike. NIH gets to decide its priorities and gets to decide who to fund — they can easily rectify these inequities with individual funding decisions. So, if there’s more training needed, maybe it would be most effective at the highest level of council and program, and it should probably focus on both implicit bias and structural racism. The research enterprise is not immune to the societal forces that have kept majority interests at the forefront in all aspects of American life. The most direct route of change is from the top down.

Granted that there are differences in black/white NIH funding rates, why is the immediate assumption that there is “implicit bias and structural racism”? What is the evidence for such a claim? Is there a simpler explanation for these differences, which is being glossed over? I think that the comment below about black investigators often being at less prestigious and less wealthy institutions is an important one, because it could affect their environment score if most of them are in the bottom quintile of environment & resources.

Very thought-provoking. I wondered if there are implicit racial undertones that black scientists are more likely to study topics that “having nothing to do with science”. While it is important to consider scientific merit in grant funding, it is equally true that scientists regardless of their race will propose to study topics that are important to them. Overall, I think it is the NIH that needs to thoroughly revise how it selects reviewers and also how funding is allocated for research purposes.

As someone who is not Black or White, if you are going to do these studies, it sure would be nice to include everyone.

I think that the blog post is leaving out two very clear, and meaningful findings from the study. One is that 33.9% of all AA/B investigators are from institutions in the lowest quintile of federal funding, compared with only 22.0% of WH investigators (P < 0.0001; table S2 and fig. S2). The study also found "that applications from AA/B scientists were nearly twice as likely as those from WH scientists to be submitted by new investigators." These factors suggest race is tied to other systematic differences which explain the gap. To be an accurate assessment racial groups should be compared for applications at 1) similar career stages and 2) similar institutional profiles. As presented this is an important step, but there is much more analyses of this data that should be done.

Very good point.

Thanks for a much needed analysis- was very insightful and good to know the trending areas/topics. Extent of research support (institutional environment etc) that can be mustered by the applying team is also very important, as ideas/ topics on their own account for less than 70% of the overall score. So in a very competitive field even those other areas could make or break the application.

I think the sole focus needs to be on Real Science, not the skin color of the applicant. If a grant applicant applies to NIH with a social sciency topic like health disparities, he/she obviously needs to pick the right topic study section to get funded. Personally, I believe that NIH is on track with funding mechanistic research to cure cancer and Alzheimer’s rather than wasting scarce money on health disparities. We all know health disparities exist and what to do about them. “Studying” this problem further is unlikely to help anyone and is just a career crutch rather than a societal benefit. I’m saying this as a layperson who wants real cures for diseases to happen. Yeah sure access to care needs to be improved, but this is obvious.

Thanks for your comment, but I wanted to clarify a couple of misperceptions:

1. Health disparities isn’t just about differences in access to health care. It is also about disparities in access to healthy environments. That includes a range of “social determinants of health” such as pollution, stress, diet, discrimination.

2. Health disparities research is not limited to social scientists. I’m a human geneticist who appreciates health disparities as biological variables that can’t be ignored in understanding mechanisms of disease. Genes do not exist in a vacuum and are heavily influenced by environmental factors, so “real science” into mechanisms needs to account for social determinants of health. For instance, zip code is a better indicator of lifespan than DNA code, despite all the amazing advancements in genome sequencing.

NIH has the fairest system of peer review in existence. It’s not about your skin color, or your name, or any kind of systematic discrimination. There is no bogeyman at NIH who is “out to get you” if you are black or if you have an exotic name. Stop whining about all the people who you imagine are biased or insensitive to your plight. They’re not any of those things. Maybe you’re just not as good as you think you are.

The extraordinary accomplishments of Western science were achieved without regard to the complexions of its creators. Now we are to believe that scientific progress will stall unless we pay close attention to identity and try to engineer proportional representation in schools and laboratories. The truth is exactly the opposite: Lowering standards and diverting scientists’ energy into combating phantom sexism and racism is reckless in a highly competitive, ruthless, and unforgiving global marketplace. Driven by unapologetic meritocracy, China is catching up fast to the United States in science and technology. Identity politics in American science is a political self-indulgence that we cannot afford.

NIH funding is not needed for people (whether black or white or some other color) to study health disparities. NIH should continue to focus on funding projects which aim to understand and cure diseases. The public goal is to alleviate suffering, not just to “study” some stuff or help out with individual scientific careers. The best way to cure diseases is to continue to fund mechanistic grants which lead to drugs and therapies. Individual doctors and scientists can “study” the disparities on their own time and on the cheap.

In order to address the last paragraph of the report above : “We briefly discussed potential implications of our findings – including the need to encourage a more diverse applicant pool, the potential value of mentoring systems to help investigators navigate the NIH system, and the possibility for NIH institutes and centers to consider discretionary funding for topics that may be under-appreciated by review but align with strategic priorities.”

I wonder if NIH has considered:

1. Doing a study of accepted proposals from HBCU vs PWI.

2. Doing a study of non white, non-AA, RO1 submission from HBCU vs. PWI

3. Doing a study of male vs. female accepted RO1 proposals from HBCU vs. PWI

4. Double blind review, the name, race/ethnicity, school name of submitter to be unknown, if possible

4. Ethnic, University, and gender composition of the reviewers to be known.

Since reviewers can be biased against the University of the submitter, can the past acceptance and rejection of the reviewers on NIH proposals be examined for potential racism/sexism…bias against HBCU/smaller schools vs. PWI/larger schools?

This is sobering. I am a black assistant professor. I work my socks off. I see little of my family at times. I try to burn the candle on both ends, writing proposals and generating preliminary results and lots of publications. Even when I have really strong preliminary results, they somehow find another reason why my proposals do not merit funding. Sometimes, I am left wondering if my proposals are read by scientists or stark illiterates picked off the streets, purely based on the mind boggling reasons they fashion to refuse me funding. When I was a co-PI on a number of proposals at my previous institution, I had quite a bit of funding. Since I moved over to an R1 University, in an effort to make a name for myself and to contribute, the story has been a sharp contrast. I have now written about 13 proposals to the NSF and the USDA and not even a single one has been funded. Students that I helped train at my other institution, who still send me their proposals to read through and suggest improvements have all received funding–lots of funding in a short time. Meanwhile, I am still slaving away trying to land just one proposal. Today, I got another rejection and I can’t seem to understand their reason for it.