32 Comments

While NIH policies focus on early stage investigators, we also recognize that it is in our interest to make sure that we continue to support outstanding scientists at all stages of their career. Many of us have heard mid-career investigators express concerns about difficulties staying funded. In a 2016 blog post we looked at data to answer the frequent question, “Is it more difficult to renew a grant than to get one in the first place?” We found that new investigators going for their first competitive renewal had lower success rates than established investigators. More recently, my colleagues in OER’s Statistical Analysis and Reporting Branch and the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute approached the concerns of mid-career investigators in a different way – by looking at the association of funding with age. Today I’d like to highlight some of the NIH-wide findings, recently published in the PLOS ONE article, “Shifting Demographics among Research Project Grant Awardees at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)”![]() .

.

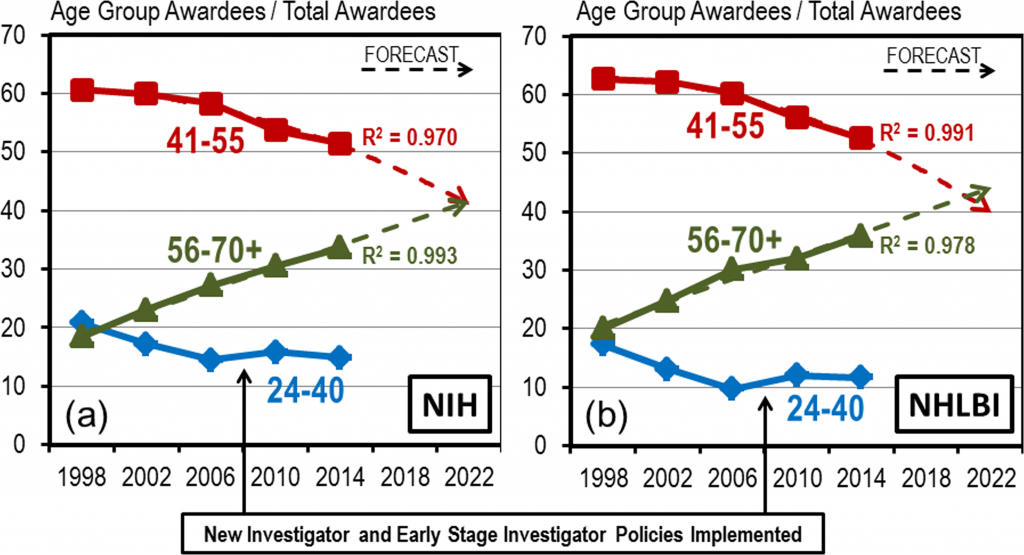

Using age as a proxy for career stage, the authors analyzed funding outcomes for three groups: principal investigators (PIs) aged 24 – 40, 41-55 (the mid-career group), and 56 and above. The figure below shows the proportion of research project grant awardees in each of these three groups. The proportion of NIH investigators falling into the 41-55 age group declined from 60% (1998) to 50% (2014).

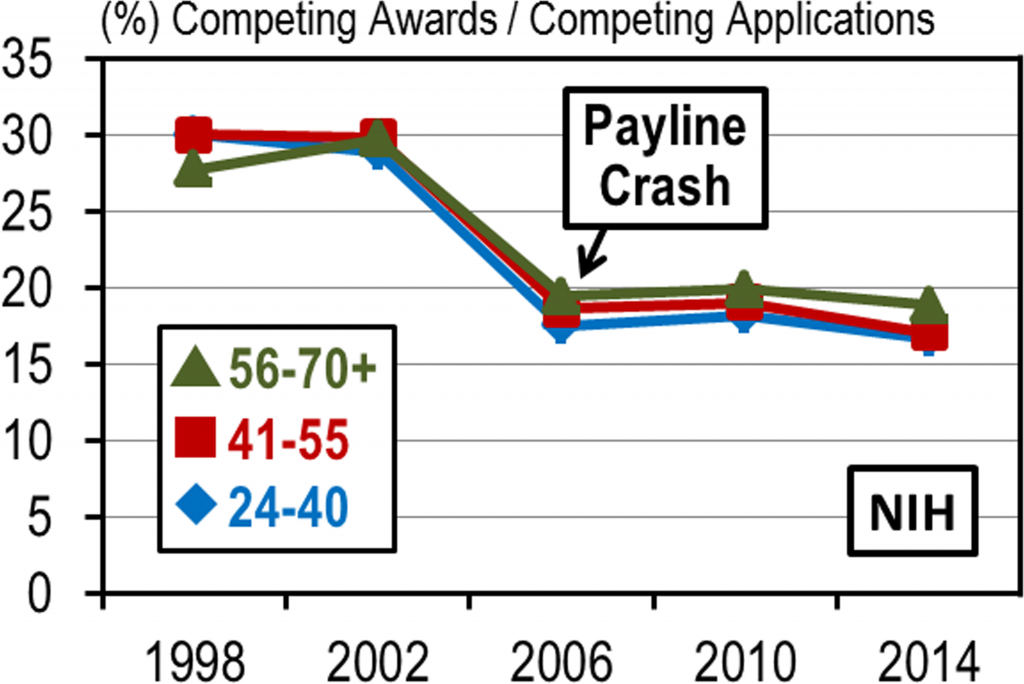

Interestingly, regardless of age, applicants have an approximately equal chance of having a new or renewal application funded.

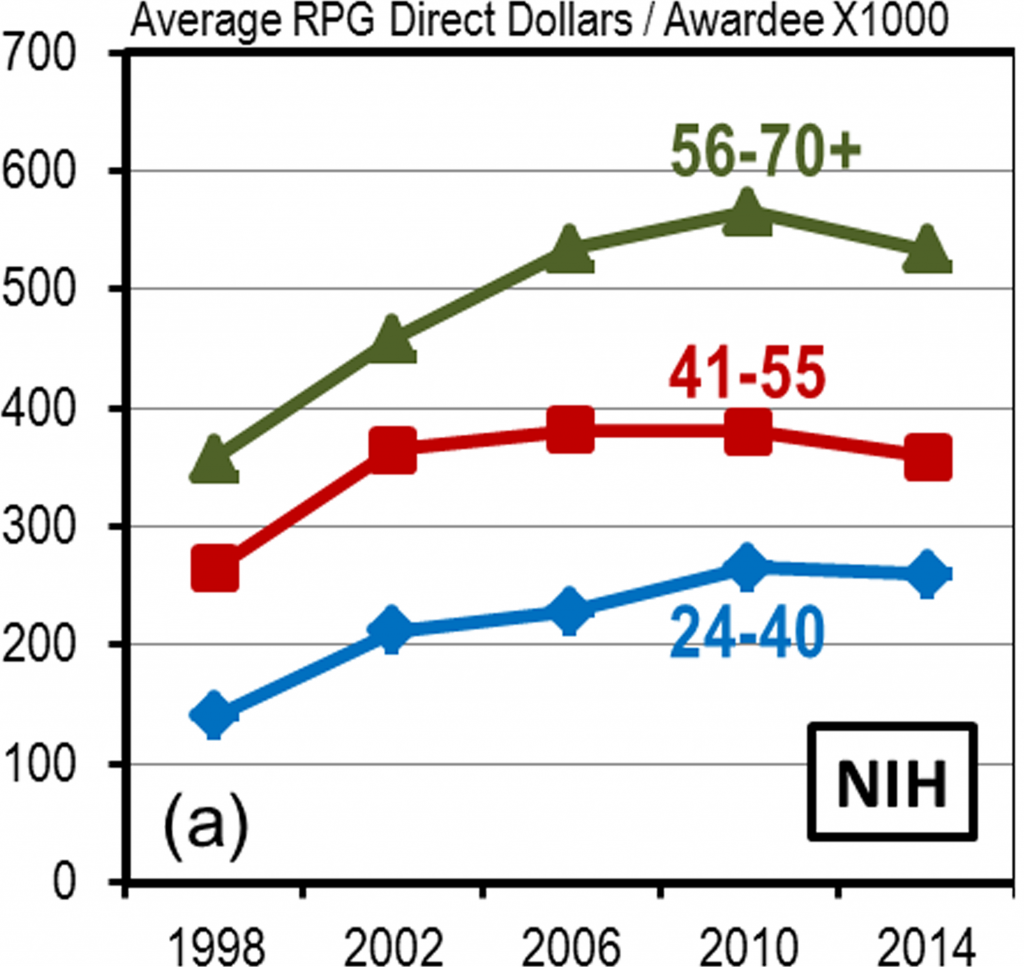

What then, might contribute to the decline in the proportion of mid-career NIH-supported investigators seen in the earlier figure? The authors propose two factors: multiple grants and average RPG award funding.

The authors argue that having multiple grants may confer an “enhanced survival benefit”, as PIs with multiple grants have a salary-support buffer that enables them to remain in the academic research system. If an investigator holds zero or one grant, an application failure could well mean laboratory closure, whereas an investigator who holds multiple grants can keep the laboratory open. Moving from younger to mid-career to older investigators, the average number of RPG awards per awardee increased ![]() from 1.28 to 1.49 to 1.54. Consistent with this, the amount of total RPG funding per awardee (looking at direct costs, specifically) is highest for PIs 56 and over:

from 1.28 to 1.49 to 1.54. Consistent with this, the amount of total RPG funding per awardee (looking at direct costs, specifically) is highest for PIs 56 and over:

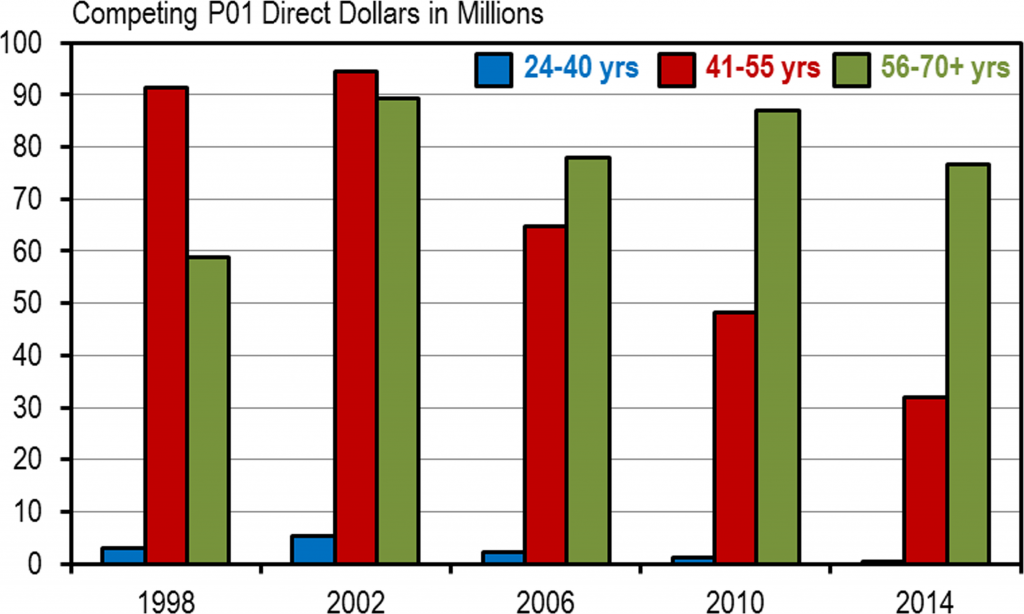

The funding spread is further enhanced by the distribution of certain types of research programs, such as P01 awards, which support multi-project research projects. The figure below shows the age group distribution of P01 funding (direct costs only) from 1998-2014. As noted by the authors, by 2014, NIH PIs age 56 and over, who represent just 34% of the total NIH RPG awardee population, receive 70% of competing P01 funding.

In their discussion, the authors suggest that their analyses should stimulate alternate explanations about why funding is being increasingly distributed to well-established investigators. They write, “For instance, a widely held belief within the academic research community is that the scientific workforce is aging because more established investigators are simply better scientists. In this belief we are all ‘Darwinists’, in that, during stressful times our first presumption is that the best survive and the merely good fall away. But what if that is not the full situation?” Of note, two recent papers in Science (here and here ![]() ) present evidence that scientific impact does not necessarily increase with experience; the policy implication is that it may make more sense to maximize stable funding to meritorious scientists throughout the course of their careers.

) present evidence that scientific impact does not necessarily increase with experience; the policy implication is that it may make more sense to maximize stable funding to meritorious scientists throughout the course of their careers.

I encourage you to take a look at the full paper, which contributes to our ongoing discussion of the age of the biomedical research workforce, and contributes to past, present, and future studies of how we can sustain the careers of those we fund as trainees and early-stage investigators.

The proportion of NIH investigators in the 41-55 age group has declined since 1998 because the baby boomers are aging. As can be seen in the first graph above, the 41-55 age group is declining, but the 51-70 age group is increasing. Proof of this can be seen in the 24-40 age group. The last of the baby boomers were just about 40 in 1998.

I continue to be shocked that NIH is trying to make decisions about proportions of career stages (junior, mid-range, senior) without taking basic demographics into account.

It don’t take a weatherman–that is, a demographer or labor economist–to know that the age pyramid of biomedical and biobehavioral R&D personnel has changed substantially in the past couple of decades, making it mandatory to develop and employ analytical age adjustments before looking any further for explanations–much less policy interventions–relating to the dynamics of investigator characteristics among NIH grantees. For example, comparing NSF’s periodic survey of doctoral scientists (of all stripes) in 1998 versus 2013: the proportion of employed health scientists age 55 and older increased from 26% to 46% of that working population, the proportion 40-54 declined from 58% to 34%. This change is somewhat more extreme but fully consonant with the trends in other personnel such as biological scientistst, social scientists, and psychologists.

One contributing factor here is likely the inability of PIs from the ‘early career’ group to move into the ‘mid career’ group. Could be many reasons for this, but I offer two: 1. these early career scientists are dropping out of the NIH funding system due to lack of renewal success, or 2. these scientists are not getting tenure due to delayed success in obtaining funding. If only 20% of early career investigators are getting R01 grants, and the average time to get one is 6-8 years, then a lot of young scientists are being forced out of the system early in what could otherwise be successful careers.

I find, as an elder statesman, that the bottom line of what I consider to be Continuing Budgeting Crisis, is the amount of funds delegated to the NIH. We hear a lot about increasing the defense budget, but nothing from the administration about science funding.

Personally I feel that the US is heading toward a third world country in academic grant funding and support for excellence.

Interestingly enough, a third world country (India) has increased its science and technology funding, and the competition for journal space (at least in basic sciences) from India and China is severe. One must wonder then, how we in the US will survive, let alone make dramatic advances like in the 70’s and early 80’s. Bad policymaker’s bad policies over the years!

The reason for the decline in young investigators is that none are being hired. The older scientists are tenured and being retained and no young scientists are being hired. As such the percentage of applications submitted by young investigators has declined because the percentage of the faculty in their age group is rapidly decreasing.

Our institution has not hired a new young unfunded faculty member in 4 years across all departments.

Were the age groups constituted in 1998 and followed as a cohort, so that people stayed in the same group over time? Or, are the age groups constituted anew each year so that people in the mid-career age group in 1998 are now in the 56-70+ age group? If the latter, those who were well funded when they were in the mid-career age group are just continuing their success in the older age group.

A personal reflection on this: I started my lab at the end of 2005. This was at the start of incentives for junior investigators but also around when the payline crashed. I received my first two R01s on the first submission, with help on one from payline boost and also renewed one of these on first submission in 2011. I was in my early 40s during this time. Since then I have submitted six triaged R01s in a row (four distinct applications but two of them triaged again at A1), two R21s (neither receiving a fundable score but one bailed out on second submission at council). I am now 48 years old. Last R01 expiring in a couple months. My lab will shortly die and we have actually published very well in the eleven years we have been in operation. There is no evidence that I can see that submitting more R01s or different types (have been rejected once on New Innovator, twice on Pioneer, once on TR01, once on Eureka) will improve this outcome although I retain a shred of hope for the NIGMS MIRA. All of this to say: I am not alone in this boat, talking to my colleagues of similar age. That middle age of 45-55 is being decimated in the current project-based funding system. Change the system or a generation (at least) will be lost…. project-based funding only makes sense if the goal is to waste the time of both reviewers and applicants.

My sympathies. I also feel the current grant situation wastes everyone’s time and makes researchers reveal all the details of new projects to others.

Michael – I’ve had a very similar trajectory as yours: good success in early career (2 R01’s, 2 R21’s, an NSF grant) but then by age 50 my funding as PI was depleted. I am now 52 and I am truly baffled about what I can be doing differently. Do I suddenly not know how to write grants or do science? I don’t *think* that is the case because I also sit on study section and can see what is being submitted and (possibly) getting funded. I have also kept up with the times by learning and incorporating new methods. I scratch my head often, wondering what I can change.

The distribution of people in the age categories does not matter when comparing success rates by age. I believe these results are capturing what I have found to be true of those in mid career. The members of the study section often know the senior people and they want them to continue their research, and the new investigators get a bump as well as recognition that they are new (a little more forgiveness on the application if it’s a good idea). The mid career investigators get nothing, are less well known, and don’t have as many publications and grants to put on their biosketches as the senior people. Additionally, in our institution, there are resources (study coordinator support, formal mentoring, etc.) that go away the minute you are promoted to Associate professor. I think the biggest issue in my department is that the senior people keep applying for funding as PI, insist on senior author publications, and provide absolutely no mentoring to junior and mid-career people. If generational identity enters into it at all, in my experience, if you ask senior faculty why they are successful they will always mention a mentor who guided them along the way, yet, they themselves feel no need to mentor junior and mid-career faculty, but to take opportunities for themselves; that could be a reflection of the selfishness of the baby boomer generation. NIH could address these issues by requiring someone below the rank of the PI to be a co-PI on an application (with the exception of Assistant Professors). If it’s not required, they certainly won’t do it in my experience.

I agree with Michael’s comments. All of a sudden investigators with a good reputation have to witness the inexorable decline of their lab…

The senior PIs are evaluated by their institutes with the same metrics as the newer PIs. If they don’t maintain productivity, they’ll be teacher- and/or service-tracked. Hence, to succeed in institutionalizing mentorship, it has to be given an analytic metric and a column in the spreadsheet used for annual evaluations. JAT promotes a worthy goal, but it’ll require cultural change.

Well, some senior colleagues of mine explained on different occasions why they wouldn’t put their junior colleagues as co-PIs on their new grant applications. They told that they did so in the past, helped and supported their mentees, who, when fledged a bit, “put a knife in their backs” and claimed full credit for the ideas and execution of the completed projects. Probably, selfishness goes both ways.

If we want to maintain a critical level of work force of scientists across all ages in the current funding situation, we need to restrict how many grants investigators can get. There are reports showing that once a PI has 3 R01-sized grants, productivity does not increase with additional funding. Funds saved then can be distributed to support mid-career scientists and scientists across all ages.

Unfortunately fat cats cried louder than all others and nih shrunk away from true reform. A lost opportunity….

It looks as though the money has remained with a specific group of people as they age, who obtained their first funding well before the payline crash, and have enjoyed long, successful, well-funded careers. I don’t have anything against them! But, it was obvious to me that this would be the trend for the NIH years ago, and I’m relieved that I left research for administration. I had my NIH funding but I could tell that the culture was not going to change and give me the career that could sustain my research the way my PhD and post-doc mentors have enjoyed. Many of my peers have done the same; the stress relief was worth giving up my research, especially considering recent elections.

I am curious whether membership in one of the centers for excellence influences success with RO1s? How does association with one of the centers for excellence increase the likelihood of funding other things equal?

One factor that has to be considered is the universities . Universities do not want to support mid career people because there are more opportunities/money for younger ones. Nearly no NIH institute supports a career change grant for a mid career person any more- eg K24s are all nearly discontinued. Universities see research as a money losing endeavor and would rather support 2 lower salary junior investigators rather than one mid career scientist. Physician scientists are also significantly declining as the salary gap between NIH cut-offs and clinical salaries keep rising and universities do not want to absorb the cost difference even if the person has grants, so more clinician scientists are not continuing on beyond their K and first R. It is just too hard to survive in research now, both from the university side run typically by accountants and because of the decline in funding in NIH in general.

Enough with the age distributions – the bottom line is that going from first R01 to renewal is the hardest of all, it doesn’t matter what age you are. Going from early stage or new investigators to mid-career is where people are getting crushed – I am seeing it all around me. What is the NIH going to do about it?

I completely agree with JAT above (and several others)- mid career scientists are not served well by the system, even if publications are steady and strong. I have served on a number of study sections and am always struck by the ‘dazzled’ phenomenon, where reviewers are dazzled by an especially strong reputation and publication record. My fellow reviewers are willing to completely overlook even moderate weaknesses in proposals from strong PIs. And it’s no coincidence that they are usually well-funded, so the rich get richer even with flawed grants. And JAT’s observation is spot-on that accomplished senior investigators keep writing grants into their 80’s- basically no mid-career scientist, especially one who teaches a lot, can compete well head to head. It’s great that they are able to continue contributing, but the NIH needs to figure out some program to give mid-career scientists a boost.

Could I refer everyone to a fascinating interesting editorial proposing a solution to some of the inherent biases in the stressed system mentioned above. It is by FC Fang and A Casadevall in mBio 2016 7:e00422-16. called “Research Funding: the Case for a Modified Lottery”.

An essential read.

Unfortunately, a lottery on the grants deemed meritorious by study section creates a randomness in the system that will be both demoralizing and inappropriate. Peer review has a number of limitations, like the jury system. No person is fully devoid of bias, and despite attempts to be fair, chances are that glib applicants will be favorably reviewed and research that has had a lot of press and exposure will be more favorably reviewed. One of the major benefits of peer review is that it forces scientists to be on their toes and keep trying hard to contribute. However, when the efforts lead to learned helplessness, it becomes counterproductive.

A simple solution exists in practicality, yet difficult politically.

Cap number of RO1s per lab @3. Make 1st easiest to get, 2nd a little harder, and 3rd only for the best of the best. Ignore the powerful elites that have 5+ RO1’s, they have a COI.

No honest person in this business needs a study confirming that excess grant money results in inefficiency – like bananas are delicious and the sky is blue, we all know it to be true.

Just do it!

The simplest way to do that may be to set the percentiles among equals. Those with 0 grants for 3 years only compete with their peers (grade 1) and get treated like those who were never funded, followed by those with less than $250,000 per year and subsequently with less than $500,000, $750,000. Over a million should require special considerations. This will reduce preliminary data considerations for those at the bottom of the barrel, while permitting their innovative proposals to rise to the top.

@3R01 are too powerful a lobby to messed with 🙁

The date need to parsed out differently. People complete their PhD and one post doc between the ages of 29-35. If they get a faculty position immediately, they take an average of 3 years to get settled and funded, which brings them to 40. So the number funder from 24-40 represents 1man yer of effort whereas the 41-55 is for 15 years. It will be more useful to distribute the data in 5-year intervals and include the number of applicants in a separate graph.

There is also a push by universities to cut back mid career scientists with little support provided, unless they are already funded. Nontenured faculty are simply given a terminal contract and tenured faculty are under a lot of pressure with tenure reviews, salary cuts, space cuts, administrative duties, uncompensated teaching, etc. This can explain the large drop between 41 and 55. The Over 55 range includes a number of faculty who have been grandfathered and do not go through the same squeeze. NIH does need to do more to ensure that faculty who lose grants for >3 years have a mechanism to obtain grants without emphasis on recent productivity. Otherwise, death of senior investigators will be followed by a big gap in innovation that will hurt the biotech industry.

About Age.

I would like to comment about senior investigators. Coming to US from Europe after completing my PhD and postdoctoral studies when I was 33, the only options to stay in science were senior postdoctoral-like positions on contingent J-Visa. After going back to Europe, where I got my first faculty position, but no lab space, I got a green card, and I could finally get a faculty position in the US that let me have a lab. Only then, I had the privilege to write my first R01. Now, the age discrimination factor, prevents me to get funding even if I am not yet decrepit….

As I have indicated earlier, I never believed that the idea of capping funds to superstars will pass. unfortunately, superstars are defined by the money they bring and not by what they actually do with the money.

Age discrimination will only make it harder, now that “young” and “mid career” investigators will get set asides.

The best method really will be to eliminate all set asides and demand funds exclusively under the standard R01 and R21 mechanisms for basic science. If P and U mechanisms are needed, sub-projects should be reviewed as individual or linked RO1s in a standard study section and the administration, pilots and cores can be added as a bonus with adequate justification.

Itappeard as is if the money is not diversely distributed as they age, those who actually got their first payment have benefited from before the issue. However, it was clear that this would actually be the trend for the NIH years back. I actually got my NIH funding too but it could be predicted the culture would remain the same and give the career that can sustain my research the way my PhD and post-doc mentors have enjoyed.

I’d like to see the same graphs produced for groups broken up to reflect a distinction between those experienced investigators aged 56-69 and those aged 70+. If one has been in science that long, maybe it’s time to consider moving on to a well deserved retirement or a change in focus from research to service or synthesis. That would leave more room for upcoming investigators- including your own students.