19 Comments

In one of my earlier blog posts, I described an analysis looking at whether attempts at renewal are successful. We looked at data from fiscal years 2013-2015, and found that renewal applications have higher success rates than new applications, and that this pattern is true for both new and experienced investigators. In response to your comments and queries, we wanted to follow up on the analysis with some historical data that looks are whether success rates of competing renewals decreased disproportionately compared to new grant applications’ success rates.

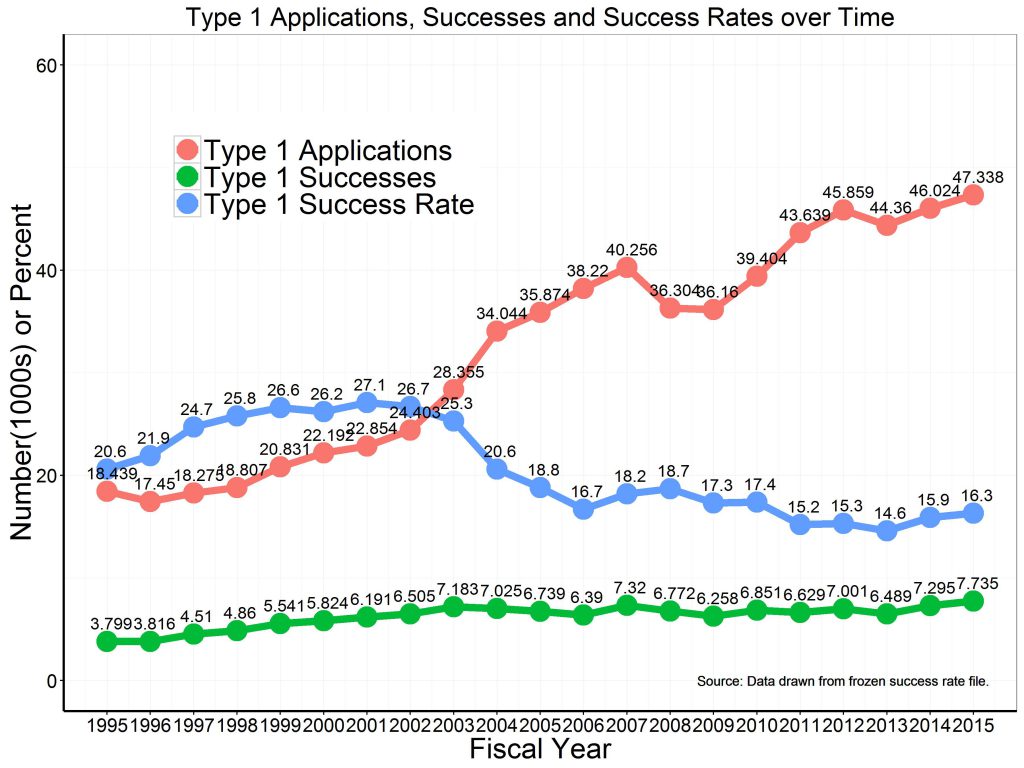

The first figure shows the numbers of Type 1 (de novo) research program grant applications and awards that we received and issued since 1995. The number of awards has increased from 3,799 in 1995 to 7,735 in 2015. However, the number of applications has markedly increased, from 18,439 in 1995 to over 47,000 in 2015. Thus, the Type 1 success rate has fallen from a peak of 27.1% in 2001 (shortly before the doubling ended) to 16.3% in 2015; the lowest success rate was 14.6% in 2013.

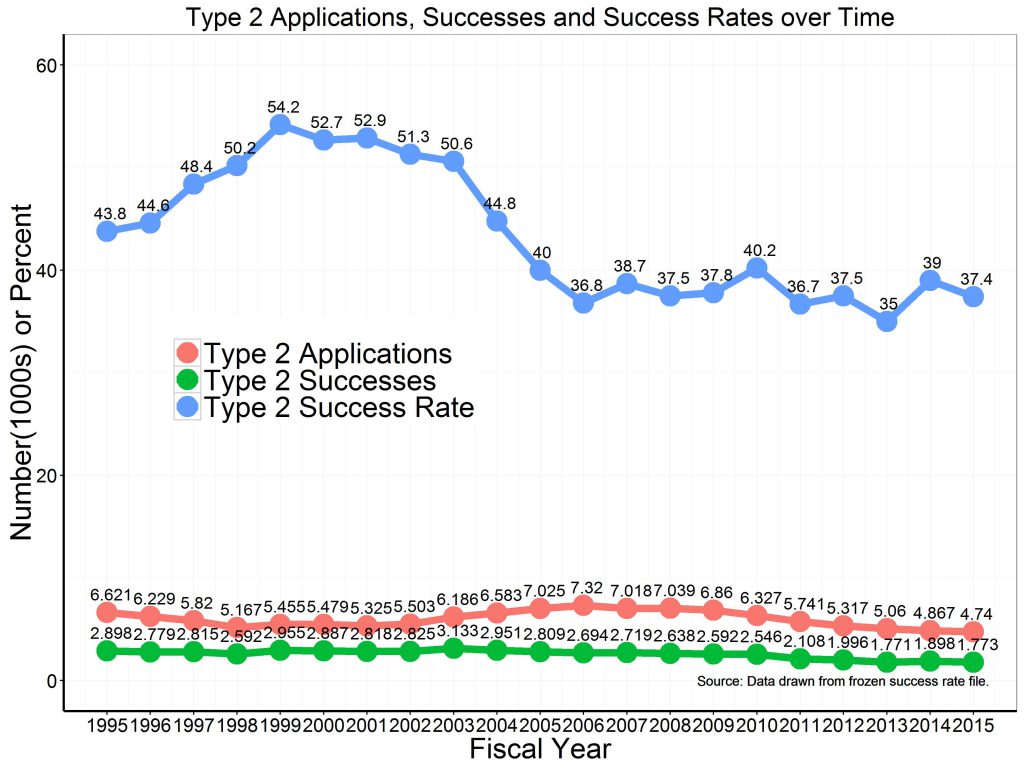

The second figure shows analogous data for Type 2 (competing renewal) research program grant applications and awards. We have seen a decline in the number of applications (from 6,621 in 1995 to 4,740 in 2015) and in the number of awards (from 2,898 in 1995 to 1,773 in 2015). The success rates have been consistently higher than seen with Type 1 applications, but they too have fallen from 54.2% in 1999 to 37.4% in 2015; again the lowest success rate occurred in 2013 (at 35%).

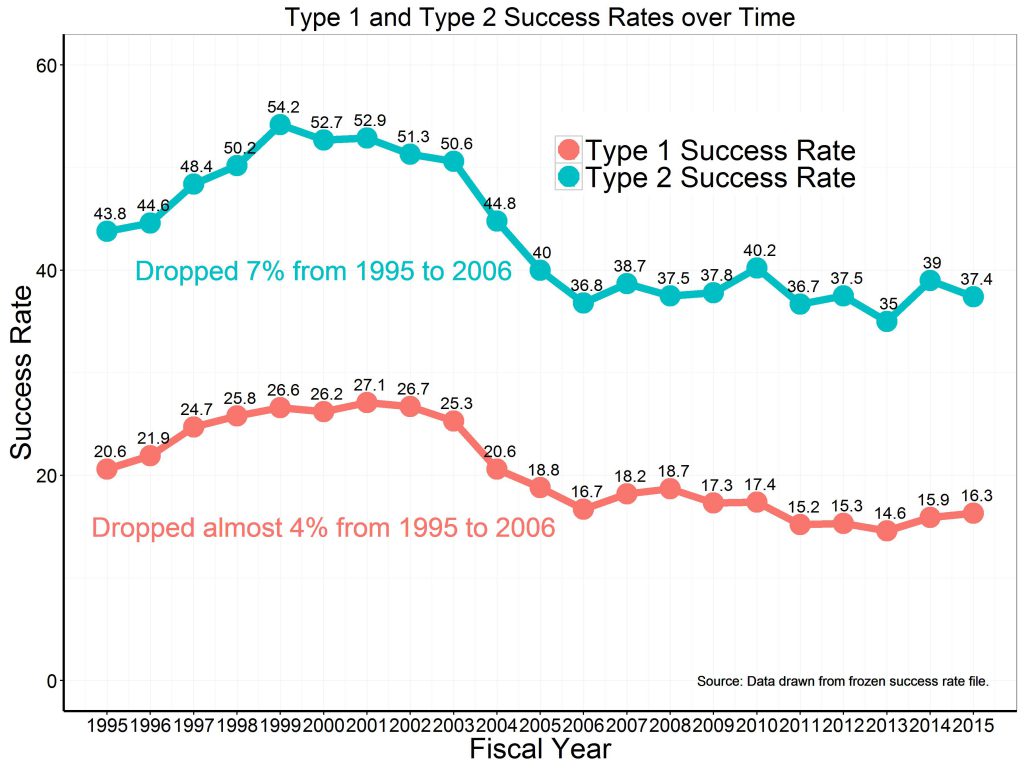

The third figure again shows the Type 1 and Type 2 success rates in comparison to each other. The trajectories have been similar; Type 1 success rates dropped by almost 4% between 1995 and 2006, while Type 2 success rates dropped by 7%. Of note, most of these drops occurred after 2003, when the doubling ended.

Putting it all together, these data show that competing renewals, while still challenging, have higher success rates than new applications. Both renewals and new applications have seen marked declines in success rates since the end of the doubling.

I would like to thank the OER Statistical Analysis and Reporting Branch for their work with me on this analysis.

Assuming I understood correctly, I’m struck by the decline in the number of Type 2 applications. Although the success rate has only declined modestly, the drop in the number of applications suggests that many have been deemed noncompetitive by the PIs themselves. Thus, another interesting measure would be the percentage of Type 1 applications that are successfully renewed. A large drop in this percentage would seem to point to a significant problem in the system.

Note that Type 2 applications are decreasing. Expected as paylines shrink projects go from Type 2 to Type 1, but suggests a lot of funding gaps.

With the payline at NCI for RO1s and R21s hovering around 7 percentile , where do these numbers actually come from?

The most impressive is the clear message that the NIH is sending. Favor established investigators at the expense of new investigators/proposals.

It would be interesting to see the drop out of new investigators doing research in the last 20 years and going with current policies established.

Are we expecting to have a drought of investigators in 20 years when those >50 y/o investigators retire? What is the plan of the NIH to prevent this event?

Best

Type 1 applications went from 18.4K in 1995 to 47,3K in 2015 (a 2.57 fold increase), while, during the same time, type 2 applications went from 6,6K to 4,7K. Partially, this is due to the fact that the system does not encourage renewals. Each time a grant goes through a competitive renewal, the new requested budget can only be 10% higher than during the previous cycle. If the grant is awarded, typical administrative cuts of over 15% keep the size of the award stagnant for decades. So, PIs opt for type 1 applications where they can request higher budgets.

Could the decline in Type 2 submissions be due limitations on budgetary increases associated with renewals?? With more and more pressure to cover a higher percentage of our salary by admistration, if I want to write a grant with a much larger scope than my original grant, I am now essentially forced to go with a Type 1 submission to request a budget of more than10% above the original grant, correct?? Otherwise I assume I need to restrict my budget and opt for the higher percentage funding on the Type 2? And if already at the $250K limit for modular, it doesn’t seem worth going non-modular to squeak out 10 more percent. Any answers or advice here?

I see no place in the R01 instructions that suggests the renewals are limited in this budgetary capacity.

It seems to be Institute specific. In my case, my Type I R01 which was submitted with a modular budget to NHLBI, is limited upon renewal by NHLBI guidelines to a 3% increase even if submitted as a non-modular/categorical budget according the FY2016 (see http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/research/funding/general/current-operating-guidelines)

Modular to Categorical

If the previous award is 10 modules, a requested increase will cause the competing renewal to be awarded as categorical. In all such cases, the NHLBI will award at the NHLBAC recommended direct cost up to a maximum of 3 percent above the level of the last non-competing award of the preceding competitive segment. The maximum may only be exceeded to accommodate specific programmatic and administrative adjustments that may be warranted or for non-recurring equipment costs. Facilities and Administrative (F&A) costs for first tier consortia are not considered in the direct cost base when calculating the maximum that can be requested.

NIAID on the other hand, seems to allow for 20% increase of the last year of the Type 1 when submitting as a Type II:

https://www.niaid.nih.gov/researchfunding/qa/pages/renew.aspx#whatcap

For the past several years—which we expect to continue—NIAID has limited the amount of money you can request for your renewal R01 to 20 percent more than the direct costs of the last noncompeting award.

It would be interesting to see how these success rates breakdown by gender over the years.

This article may be of interest: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3379556

Type 2 applications are in decline because of the budget restrictions on renewals. You get a budget in year 1 of the initial grant and it is administratively cut 20%. Then over the next few years, it fails to keep up with inflation as salaries go up. Then when you apply in year 5 for renewal, the year 6 budget is a function of the year 5 budget and if your were “sequestered” in year 5, you are stuck.

It would be interesting to see the breakdown of universities that have Type 2 grants. In my opinion, those are the same universities up in the North/Northeast who traditionally get funded at a higher rate than the rest of the country. NIH funding has recognizable geospatial disparities that is a long tradition.

Interesting numbers and discussion overall. I would suggest that one reason for the great increase in “new” applications is the need to apply multiple times to get one grant funded. When more get funded, as with renewals, the actual number of grants drops!

Assuming the present funding rate is around 10% (so accounting for triage on the initial pool of applications), then in theory one must write 10 grants to get one funded. Each of these must be reviewed, which means more funds going toward administrative costs for that. And if one is working in an “unpopular area”, e.g., a field that is not making headlines and demanding special support, the number may be even higher. The newest approaching (or unfortunately, already present among us) plague becomes the first funded.

Rather than suggesting that more money be allowed in renewal applications, the obvious point of the numbers is that raising the funding levels for new proposals would be the fastest and easiest way to raise the success rates. Then we could all spend more time on what we are supposed to be doing, i.e., working in lab.

And one other point on those expanding budgets for renewals: there is a large gap in many of the larger universities between what the PI is paid and what the people in his lab do. The NIH has made steps to reduce this, by insisting that those who work longer as postdocs be paid more. One unfortunate effect of this is that those professionals are effectively not normal employees, and face an up- or out- situation at the 4-5 year mark. This may be just at the time when longer research projects are looking more promising, and when they really begin to be able to be scientists in their own right.

Perhaps we should look more at automatic increases on salaries above a certain income level, say those who earn more than 3x what a 5-year post-doc gets paid according to the NIH scales. After all, that post-doc usually has more demands on his or her salary than the PI does, with the need to start a family or buy a house, or just be able to take a nice vacation with loved ones. We should not demand that becoming a scientist means living in poverty or being supported by a spouse.

First, I am struck by the timing of the marked change that occurred ~2002-2003; any thoughts? The change to grant length happened in 2010 so it wasn’t a factor, but likely contributes to the ever climbing trend for Type 1. It is the norm now to put in multiple (lots!) applications in the hopes of hitting on one, and you need at least two grants to be able to afford personnel if you are going modular; I would like to see the break out of how modular (which hit all of NIH in 1999- maybe this was a factor to the change in 2002-3?) vs non- modular plays into the success rate because there is only so much money and if more are non-modular then the numbers will go down.

The submission number by a single PI obviously also has contributed to the escalation in Type 1 proposals which obviously will drive down the success rate. It hits everyone, both new investigators and established alike. The lucky few who do get an RO1, make substantial progress, and can take that to the next level for a renewal deserve it when they get it because that is probably one of the hardest things to do in this new era; only 1773 of those were funded last year across all of NIH, and the number is falling. It is clear that the old way of doing science (i.e., get and RO1, and renew it) is going away. Now it is get an RO1, and repeat any way you can.

Mike- you left out a critical number-between1995 to 2015 the % of all funded R01s that are funded as renewals (Type2) has dropped from 43% to 18%, while new R01s (Type1) correspondingly increased from 57% to 82%, i.e. almost even to 4:1. A lot has changed in that time… But bottom line: To me this would seem to be a big problem in terms of the NIH getting what it has paid for in the grant proposal, and how proposals and investigators are evaluated. It would seem that delivering on what was promised is of limited value in the current system, a bad message all around.

here it is:

Type 2 Direct Cost Cap Policy at http://www.cancer.gov/grants-training/grants-management/nci-policies

The NIH statistics paint a rosier picture than they should. The real situation is even worse than that shown. For NIH statistics, if you apply for a grant, don’t get funded, revise and reapply as an A1, don’t get funded, revise and apply for an A2 and finally get funded, NIH counts it as 1 funded grant/1 application. In the real world, that is 1 funded application out of 3. And it doesn’t consider at all the delay of close to 1.5 years that this creates.

I would like to see statistics that reflect this harsher reality.

The NIH funding system is one that is failing, both in terms of review and support mechanisms. The first step in an intervention is to accept a failure and not spin it as being positive. We all know it is not. Many many scientists, engaged in basic sciences, are not NIH funded, despite the all the articles that engage in stating the opposite. The IRGs are self-serving or network-serving and are not unbiased, and clearly not supportive or encouraging of pursuing the scientific endeavor. So, as a PI ages, it is also possible that she/he gets jaded and that too will account for a drop in submissions. Many are in the “jaded by NIH” category, will be (fortunately) out of this hunt for $ soon, and will leave the sciences forever. Good luck reinventing the arcane.

I would like to note that these data do not demonstrate that a given PI with a choice of submitting the same application as a type 2 or a type 1 has a better chance of funding with a type 2. In fact, there is little reason based on the peer review and funding process for a typical R01 to expect a difference in funding likelihood for such a PI.

I am assuming that the type 1 data include applications from PIs who were either not previously funded, or at least not previously and recently funded for a project closely related to the new application. A type 2 application means that the PI has been funded for a related project (type 1 or prior type 2), and likely has data and publications from the latter that strengthen her type 2 application.