11 Comments

In August I presented data regarding the well-known increase in applications to NIH over the past decade. In “More Applications, Many More Applicants” we looked at the source of increase in competing applications, and presented data on the numbers of unique NIH applicants per year. (Further analysis of data pertaining to the number applications per principle investigator was posted to the blog later that month in “Do More Applications Mean More Awards?”, and also discussed in 2011 blog posts on the number of grants per investigator.)

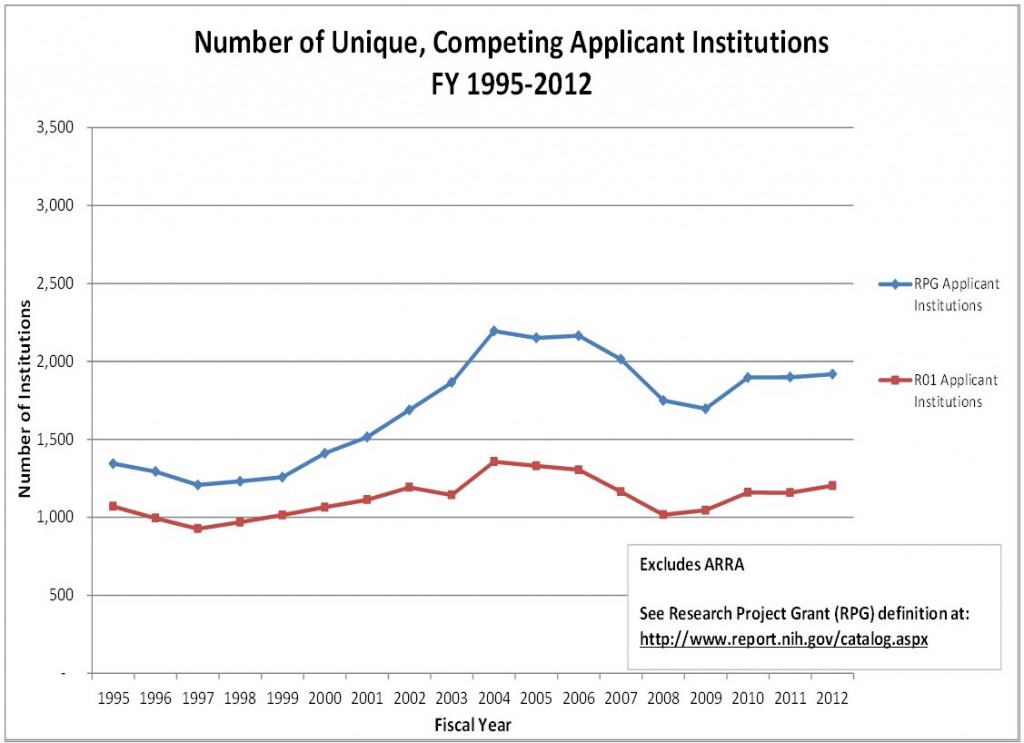

Another question related to understanding the increase in applications submitted to NIH is, how many different research institutions submit applications each year? So, my staff and I took a look at the number of institutions that submitted competing research project grant (RPG) applications each fiscal year, going back to 1995. In addition to looking at all RPGs, we also looked at data for R01s only.

It’s interesting to note that while the number of unique institutions with competing R01 applications has been relatively stable, the number of institutions submitting RPG applications has increased.

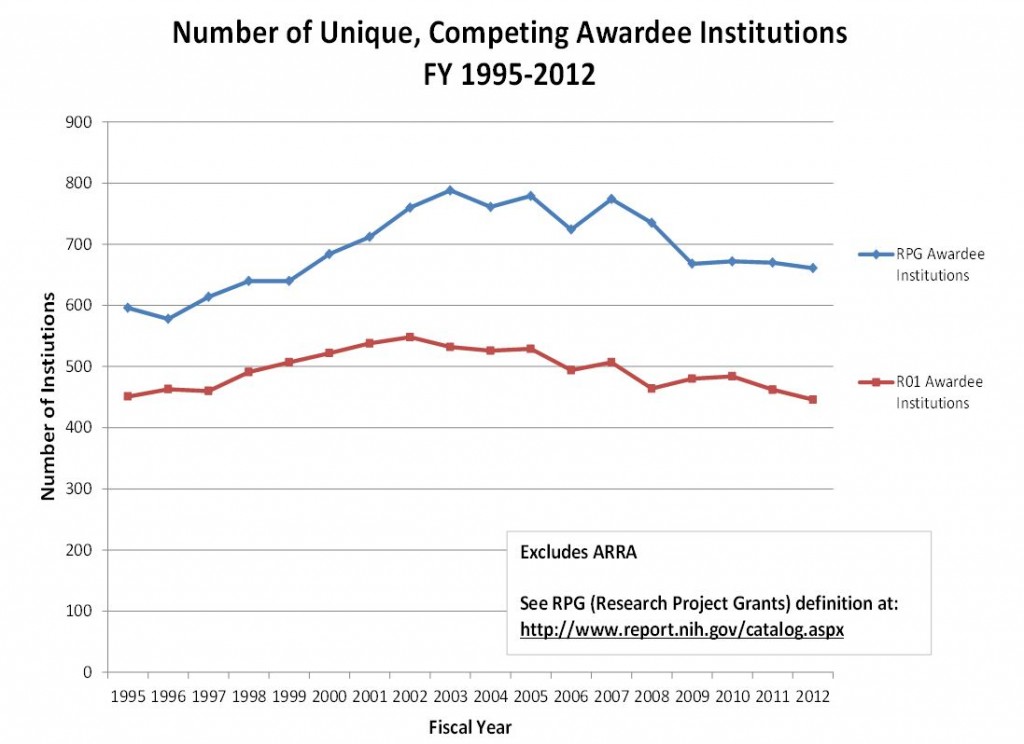

We also looked at the number of award-receiving institutions for comparison, to see if the trend is similar.

Again, the number of unique institutions receiving R01 awards each year has been relatively stable, while the number of institutions receiving RPG awards has slightly increased.

This data provides a bit more insight into NIH application trends, and we’re continuing to work on additional analyses to learn more about these applicant and grantee institutions. Stay tuned.

Your analyses continue to dance around a much more critical question that should guide your shorter term tactical thinking on this. Are or are not there changes in the number of funded investigators and are their changes in the amount of total direct costs that they carry and the number of applications they need to maintain that amount?

There is a perception that your changes in application numbers simply do not reflect reality for PIs. It has been suggested in many corners that the reason is that you are looking at numbers tied to Fiscal Year instead of actual PIs. Different investigators who submit one grant per year, one ever three years or one every 5 years are counted the same in your per-FY accounting (right?). Yet this represents a much different reality with very different solutions.

If the same investigators are maintaining about the same number of grants but need to do more grant churning to accomplish this success, figure out how to stop the churning. I can think of many ways- roll over good scores, extend noncompeting intervals (a la the R37), use the Programmatic priority more prospectively (instead of bailing out the desperate at last minute with R56s), etc.

If the PIs are having to secure more grants to maintain the same purchasing power this entails another set of solutions (raise the modular limit to $350K, say.

If there has been an increase in the number of PIs seeking funding (again, your per-FY cannot get at this, you need to look at the population that is funded at a given time, not just current year successful applications) from you in the fact of shrinking budgets, this entails yet a different set of solutions.

I simply cannot understand why it is so difficult for you to assess the data and your virtual workforce in a way that generates evidence-based actions to improve the situation.

It’s time for an economy of scale in indirect costs. The PI’s are like donkeys pulling an overloaded cart. A 350K grant is costing over 500K a year and few PIs can pull that kind of weight with sufficient quality yearly publications.

If there are only 500 institutes receiving about 7.5 billion dollars in indirect costs at a rate of 50%, thats an avg. of 15 million per institute or enough to pay the salary of roughly 250 employees per institute not directly involved in research. If another institute obtains 100 million in grant dollars, the indirect costs could employ 750 support employees not directly involved in research. These are areas of cost to the NIH system and grants that the PIs know not how to account for (need transparency). It’s no wonder PIs have little idea where the money and grants are going and why their funding chances are so low. Indirect costs are a huge load on the PIs and the NIH budget.

If there are no indirect costs, how will institutions pay for the people who work in the library, sweep laboratory floors, collect laboratory trash, dispose of the laboratory biohazardous waste, receive and distribute FEDEX shipments, and administer/monitor compliance with the FCOI, RCR, human subjects research, animal care, biosafety, select agent, bloodborne pathogen, and radioactive material regulations? Having had first-hand experience with indirect cost rate negotiations, I can tell you that the rate at our institution (~48%) doesn’t come close to our institutional costs. During the course of my 20-year career as a bench scientist and research administrator the regulatory burden on biomedical research institutions has exploded, but there has been no commensurate increase in indirect cost rates. So, in my opinion, the “indirect costs are excessive” argument needs to be retired in favor of other strategies for controlling costs and increasing the number of funded PIs.

I don’t think indirect costs are the issue. You mentioned that the funding goes to “support employees not directly involved in research,” but employee salary this is only one eligible expense overhead funds can go to. It also goes to fund building lighting, heating, infrastructure, and a host of other vital costs, all of which are required to be funded or else the research won’t be able to happen. These funds would otherwise come out of the university operating budget, which would lessen the amount the institution would have for other expenses (primarily faculty salary).

As for transparency – each institution that receives federal funding has their own indirect cost plan, and most openly publish these somewhere on their respective websites. As such, the need for transparency on IDC rests with the institution, and not necessarily NIH.

I argue that now is the time for an economy of scale in indirect costs. In other words, each successive grant received should have a lower indirect cost. Large institutes should be more productive and efficient than small institutes (i.e. have lower indirect costs). If not, what is the point in funding grants at 500 institutes and not 1000? What many institutes and the NIH have now is called a diseconomy of scale. Should each institute be rebuilding the infrastructure of prominent institutes or the NIH? I do not argue that indirect costs are there–only that there is no efficiency in the management or we are rebuilding like/similar institutes.

That doesn’t make any sense. Large institutions have much higher IDC expenses than smaller institutions and already receive low rates. If you lowered the amounts even more you would be crippling them. I don’t understand your negatively towards IDC – Again, the money does not go to building infrastructure but paying for actual costs incurred by the institution for the research activity. Without a high indirect costs rate, the institutions would not be able to afford to let the PI do the research in the first place.

Another thing driving churn, particularly at institutions with large numbers of ‘soft money’ researchers who depend largely or entirely on NIH grants to stay employed, is the limit on PI % effort from a single grant. As an adjunct track researcher at a University of California (with zero prospects of any teaching position or other source of non-grant money), I need at least two grants at any one time to cover my salary, so I’m constantly applying for grants (and spending less time than I should concentrating on science and my two existing grants). Increase the % of effort that I can draw on from a given R01, and I’ll probably reduce the rate at which I apply for grants.

I appreciate the data being shared with the community, but the description is a little inaccurate (probably wouldn’t be acceptable as a figure caption in a journal). Yes, the number of unique RPG submitting or receiving institutions has increased compared to 1995, but the dramatic increase was during the doubling period from 1998-2003. A much more realistic interpretation of the data is to look at the last decade since 2003. Since then, the number of institutions in all four categories has declined. This suggests that institutions are being lost to science, as well as individual scientists.

I personally am always a glass half-full kind of guy, but it seems that these newsletters are often cheery and positive out of proportion to the reality that science is in a crisis state. This section is one more example.

Agreed it is best to look through the lens of 2003 onwards, but this should carry parallel number from 1) BDRPI, 2) NIH budget, 3)Federal budget

everything is relative.

A lot of growth funding goes toward the expansion of infrastructure without the expectation that it would be tied to continuous legacy NIH support

If it were a 50% indirect rate across the board, it would be less of a distasteful pill to swallow. The fact is that many of the “top” institutions have indirect rates in excess of 75%, some more than 100%. Our own Institution has a negotiated 88% indirect rate, yet a bigger Institution a few blocks down the road has only two-thirds that rate. Despite these ridiculous rates, our Center (4 senior PIs – all funded, 6 junior PIs – some funded) has only a “business manager’ (aka grants person) and no current administrative/secretarial support or any other ‘central’ personnel, patchy IT quality and support, and investigators have to insure their own equipment (even though the Institution ‘owns’ everything) and pay for additional benches and desks if none were installed in a particular area!!. I agree with the comment that a lot more transparency on indirects is needed as I for one want to know where all these dollars go, just like we have to justify and explain what all our research dollars are spent on. Some serious auditing of “expensive” institutions and NIH-enforced belt tightening on spiraling indirects would at least go some way to keeping more research funded.

I agree – there is a great disparity across institutions in what they charge for overhead rates. Mine charges 69.5%, however, our core facilities are expensive, are required to submit grants to support their operating costs, the animal facility charges a rate that allows them to cover their costs and the portion of my salary that is covered comes out of these indirect costs. Therefore, while I agree that there needs to be administrative services, maintenance of the space and infrastructure to allow a funded investigator to carry out his/her research, it does seem to that that the institutions are able to negotiate rates with the NIH, while we investigators are stuck with a modular budget.