68 Comments

Recently we explored the increase in average age of new investigators. While that average age has remained relatively constant over the past ten years, we are seeing something different in our entire pool of principal investigators (PIs). Today, I want to discuss this by comparing the average age of NIH PIs to the age of faculty in medical schools using data generously provided by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). We recognize that slightly more than 45% of all awards are made to PIs that work outside of medical schools, but the AAMC has been very successful in collecting information on faculty that work in that setting, and it’s interesting to see the comparison.

(This video does not have an audio track. If you are unable to view it, you can also download it. View the presentation slides here.)

The NIH started recording the age of most PIs around 1980, which is why the presentation above starts at that year. As you move through the years from 1980 to 2010, you can see that both populations of faculty and PIs become less compressed in the age period between 28 and 65. In more recent years, you see fewer people entering the faculty at ages 28 and below, and very few people receiving an R01 award before age 33. But, the biggest difference is seen at the later ages. The elimination of mandatory retirement during the 80s and increasing life expectancy allowed people to remain employed much longer[1]. We also suspect that the current economic situation is forcing many people to reconsider their retirement.

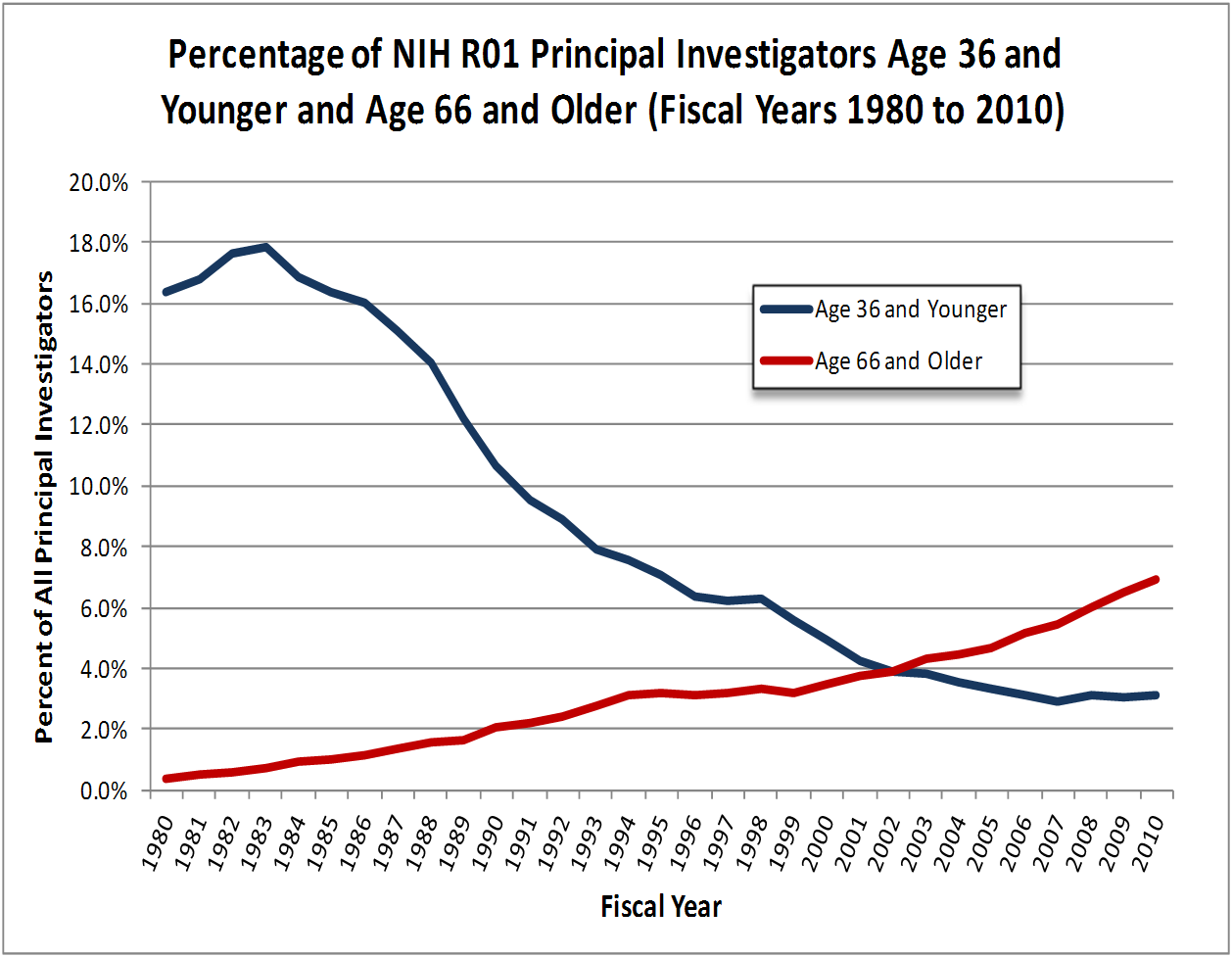

In 1980, less than 1% of PIs were over age 65, and now PIs over age 65 constitute nearly 7% of the total. In parallel, in 1980, close to 18% of all PIs were age 36 and under. That number has fallen to about 3% in recent years. These are big changes.

Another factor that jumps out is the increasing gap between entry into faculty and receipt of the first R01. Although not all AAMC faculty members apply for NIH research grants, the gap is interesting and suggests that institutions and other non-NIH funding sources are increasingly responsible for research start-up costs.

When we produced this same presentation five years ago, I had predicted we were at the cusp, and that the average age of a supported NIH PI would remain relatively constant going forward. However, obviously, I was wrong. As we continue to look at the age distribution of NIH PIs, we will keep you updated.

How does this compare to overall age distributions in US population? I wonder if this just follows the trend of the aging of the large baby-boom generation. Is there just a smaller pool of younger candidates to begin with? Or with more PIs competing from the over 36 age group, it’s forcing more young scientists to pursue post-docs or industry positions?

@Samuel Hamner

Given the large increase in new biomed PhDs over this time period, the baby-boom generation doesn’t explain the change. More probably do go straight into biomed industry, but given the biomed R&D constriction in many areas, that probably explains only a fraction of the gaps. A lot more new PhDs are in temporary jobs like postdocs or leaving research.

I’m curious about is how these percentages represent actual numbers of grants. For example, http://nexus.od.nih.gov/all/2011/05/13/update-on-myth-busting-number-of-grants-per-investigator/ includes the total number of PIs on grants in 1986 and 2009. In 1986, there were 16,532PIs of which around 16% were age 36 or younger. In 2009, there were 26,183 PIs of which around 3% were age 36 or younger. That means, despite the large increase in PIs, the raw number of young PIs plummeted from around 2645 to 785. This is depressing.

Billions of dollars spent on so called NIH research and there is nothing. Cancer still around and increasing, HIV still around and mutating………..

This whole issue is a major disappointment and waste of tax payers money..

An alternate agency such as NSF with similar strategies should take over or replace the NIH. The NSF had many major accomplishments compared to that of the NIH no to mentioned all applicable not just make beliefs…

I hope the government would wake up one day and make a major decision of re organizing the NIH or even return back research to the NSF as it supposed to be…

Jad

It is obvious that you do not have any remote clinical understanding of the pathologies you are talking about.

Whoever talks about “cancer”, as if cancer was a single disease, was unrelated to the aging of the general population, or had not been a field in which big advances have occurred, should refrain from criticizing.

Bad knowledge of facts makes for useless comments about policy matters. I well remember, as a medical resident in CO during the ’80’s, hearing then-Gov. Dick Lamm asking, “why spend money on AIDS patients? It’s an inevitable death sentence.” That recollection encapsulates why NIH-funded basic science research (which should be a larger part of the pie now than it is), along with clinical studies, has such power to change the world for the better: yes, more progress is still needed, but huge numbers of people now die of other causes with adequately controlled HIV infection, after long contributions to society after their HIV infection. [incidentally, age-adjusted mortality rates from cancer have been falling, too, just not as dramatically as the historic decline in deaths from atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases.]

Approximately one out of every 6 FDA approved drugs started with basic research at the NIH. I fail to see how that amounts to “nothing.”

If you don’t think anything has been done about HIV/AIDS in the past 20 years you could stand to do some reading. Infection used to mean a prognosis of months to a few years, now it is decades. Frustration with the pace of progress is no excuse for willful ignorance of the advances that have been made.

As a new Assistant Professor I feel honored (lucky?) to be in the position I am. However, I am amazingly stressed out trying to get my first R01 and this just adds to my worry. I have read how the NIH means to support young investigators, but so far I have yet to see any real proof of this…

Like Sting said, “I don’t ever want to play the part, of a statistic on a government chart.” Hope I can still break the mold!

I agree. Considering most innovative ideas are generated before 45, you can estimate how much money is wasted. Lots RO-1 grants end up just a couple papers, that only cited by themselves.

NIH’s reviewing system has major problem. People stated they are NIH reviewers in their CV, to show off their power. NIH should forbid this.

I am a “young” investigator, being under age 66. I am considered a new investigator, as it has been less than 10 years since I received my PhD. I received funding from the NINR in 2010 for an AREA R15. It was my first submission to the NIH. I believe my success is due to a number of factors, mainly 1) superb mentorship, achieved by me reaching out and asking for help, and showing I was willing to work for it; 2) a number of years of writing proposals to other agencies which were not funded, but supplied excellent feedback and learning opportunities; 3) input from multiple sources, including academics from other institutions and the community; 4) willingness to ask questions that are basic to Program Officers, but not to me; 5) being in the right place at the right time (i.e. luck); 6) attending training opportunities from the NIH to local offerings; and last, but not least, 7) persistence. It certainly is not a 9-5 endeavor. For those who have families and other interests, I can imagine it is a difficult juggling act. For me, this is what I live and breathe. And I love it.

Would it be possible to release the data behind these yearly histograms as total # of PIs by age rather than percentages?

It would be nice to also include how many new PIs appear at each age (which would also let us calculate the ages when PIs stop getting NIH funding). Ideally, I’d like to see each age broken down into their years of NIH PI support to date. (i.e. in 2009, 400 PIs had 10 years of NIH support, 300 PIs had 9 years, 200 PIs had 8 years…). For the early years, it might be possible to estimate this by the starting date of their active grants in 1980.

This information would make it possible really quantify and predict how the changes in early grant support affect grant distributions 10 years later.

Here is the data as number of PIs: http://report.nih.gov/FileLink.aspx?rid=828.

How is “med school faculty” defined in this analysis? Is that the number doing research or does it include clinical and educational faculty as well? It looks like the vast majority of faculty are unfunded but that seems unlikely unless you are considered non-research faculty in the denominator.

It’s any medical school faculty. The definitions are set by the AAMC. For more information, see https://www.aamc.org/data/facultyroster/.

This time chart of the ages of NIH grant recipients is not that useful because until 1994 there was a mandatory retirement age in the USA of 70 at universities. Much of the change in terms of the grants going to older scientists appears to me to be related to the end of this policy. There is no longer a mandatory retirement age dictated by the US government. Thus, older scientists are now still competing for grants. You can even see this in the bend of the lines above.

I just left this comment on the 2013 budget and NIH research grants link, but think it applies here as well:

Forget about direct/indirect costs—just put a cap on the number of active R01s / center grants that a PI is allowed to hold at once. Let’s say no more than 2 R01s or 1 center plus 1 R01. The only way you will be able to keep the upcoming generation (and btw, early-stage and new investigators are not the most vulnerable stage now—it’s those of us who are trying to renew 1st (single) R01 that are likely to be weeded out of science) from dying in the pipeline is by implementing some similar sort of real ‘wealth redistribution’ policy. The senior folks have had long, productive, lucrative careers with multiple simultaneous R01s/center grants. Isn’t it time for them to stop viewing things from a narcissistic lens (‘I need to make my biggest discovery yet’) in favor of saving the field that they purportedly love? If they want to see their fields continue to flourish in the future, they have to be willing to give up some of their excess in order to keep talented mid-level investigators in the game. There is NO program at NIH to protect these careers, and I would argue that we will be the ‘lost’ generation unless NIH (uniformly across institute) applies a stringent ‘no more than 2 active R01s at a time’ policy!!!!!!!!

NIH used to have a mechanism called a “First Award”. Are there really PIs over 80? Maybe now they need a mechanism called a “Last Award”.

Don’t get frustrated – the statistics doesn’t account more people being called faculty (research track, clinical track) and doing more postdocs. If you already took those hurdles and are a bona fide faculty, you stand a good chance.

I congratulate you to finally stating this – I said so for a long time and was always told that is not what statistics say – but they do! In study sections we are encouraged to favor young/new investigators, but are not allowed to discriminate 80+ yo veterans, who often come to the US because in Germany, the Netherlands etc. there is still mandatory retirement (around 69). So, not only do profs here stay on longer, there is a net influx from other countries.

The system is broke – retirement benefits that Universities paid are paid so one can retire, not to keep going and be contributing to an estate while working until death.

I wish we could change this somehow and encourage older Profs to be more altruistic -Please, retire early so other can take your place once you can comfortably live on your retirement. But as honored emeritus Prof let you be honored, be allowed an office, access to journals, and be available as advisors for the young. It is a sad fact that when I say this, I am considered illusionary – it seems everyone is after the money and eating their young on the way. I will not do so!

It looks like the average age increases about one year each year. Is this the same cohort of people receiving funds over their entire careers? Certainly there are researchers who continue to do wonderful work, but there is also, after serving on review panels, an improved ability to write proposals that will be funded. How can NIH ensure that great ideas are better rewarded than grantsmanship?

It doesn’t surprise me, I had my first RO1 at about 36-37 but had 5 simultaneously most of the time since then. In my case, It was training. My first RO1 was within 1.5 years of finishing my fellowship. The good part, I am doing some of the best work of my life now so life doesn’t end after 40, to some degree it takes off.

I think he means 2 not 5 based on his NIH Reporter profile for all you dissers.

Though you focus on the increasing average age of PIs, one constant over the years has been that the shapes of your curves, with the steep dropoff in middle ages, suggest that very few people are able to sustain NIH funding for much more than one funding cycle. What’s the “half-life” for NIH funding for the average PI? What percentage of PIs with initial funding are still funded 25 or 30 years later (i.e., the length of a career). The reality is that, although it may be difficult to get initial funding, it is nearly impossible to sustain a career in biomedical research.

With respect to being a Young Investigator, I was told early on to focus on getting good period. That will carry you through. Learn everything about writing great grants (read them when you can). Read everything on grant writing you can and let people who are funded (not people who think they know what you should do) read your grants. The problem with depending on Young Investigator programs is that the jump between 12 percentile and 7 percentile is a mountain. If you got there without a bump you are set for the future, if you didn’t next time around you may be a one hit wonder. Now more than ever review panels favor new ideas over track record. Become an expert at writing great grant and measure yourself the pack, not trying to squeeze through as NI. That is what I did and my career took off.

Curious if this is driven by the K awards as this would delay the first R01 potentially by a definite amount of years, as opposed to preliminary data for an R01, which may be a variable amount of time?

The age distribution of R01 PIs has increased much faster over the last 30 years than the average age of medical school faculty, because R01s have funded largely the same group of investigators throughout their careers. This shows how the current peer-review system rewards reputation over innovation, and funding history over potential impact.

Does the histogram show the data for unique PIs? that is to say does each PI contributes a single count to any given bin whether he/she has one, two or more awards? or alternatively does the histogram simply bins the ages of the PIs for all the awards (in which case any PIs with multiple awards will be counted more than once)?

This may be important for understanding how resources are allocated to young investigators.

Thanks for the data.

Interesting data. Regarding young post-doctoral scientists. I am approached by many with biomedical PhDs from very respectable education institutions who indicate that industry, small or large, is their preferred future employment. Anecdotally I believe this is a big change from the 80’s when I and my colleagues were all focused on academic positions. When questioned, the young scientists usually indicate that it is a life style decision.

As a non-profit that provides “seed grants” to PIs to work on a rare disease, I am surprised that you admit, “other non-NIH funding sources are increasingly responsible for research start-up costs.” I am not sure that this “abdication” is a good thing. We do it because we have to–no one else will. What we have found out is that attracting new, young PIs is critical to advancement of the work. The NIH should make every effort to do the same, in my opinion.

P.S. It was refreshing to read someone in your role as admitting that they made were wrong!

Let me throw out something provocative. For context I am mid-career/mid 40’s. I received my first R01 at 41.

It is generally the same investigators who are benefiting from both 1) relatively high percentages of R01s going to investigators aged 30s during the 1980’s; 2) increasing percentage of R01s going to investigators aged 60s now. We are 30 years on, and the same group of people are benefiting from getting more R01s and having skill post docs train in their labs for longer periods of time.

Could it be that this older generation is simply protecting its own? It should be considered.

Certainly other things at play: many faculty hired during 1970s and 1980s than now, funding rates higher then, large swings in funding rates in the last decade+. But as things get more difficult now, it is young faculty who are suffering and older faculty who are having fewer hardships. I am hoping the shift in focus towards translational research will benefit younger/mid- career faculty.

Shouldn’t that be easy to examine by knowing the distribution of ages for people on study sections who rank the proposals?

If it is the older generation protecting its own, then shouldn’t the distribution of ages on the panels be roughly the same as the distribution of those funded?

No, because you can influence the study sections simply by your power. It is well known that NIH “confidentiality” is anything but, and a young PI risks career and reputation if they shoot down big names (not all, but there is a mafia of sorts). I’ve sat on panels, I’ve seen the influence from afar. Young PIs fall over themselves to get it good with the power brokers. I’ve seen young PIs threatened when they mentioned quietly that Big Boss X has data that is wrong. Some fields are worse than others, but it is overall a LOT uglier than most would believe.

Scientists are not selected for good behavior. They are not saints. They are as ruthless and competitive as any human sector. Science itself is so productive because of the built in mechanisms to counter-act much of human nature. But it’s not perfect or all cleansing.

US Science has a big problem. Funding down. Mafia active. Handful of gatekeeper journals staffed by non-practicing editors who can’t handle the material. Young scientists as a whole starving. The Literature Retractome growing.

These things are all interrelated.

The old people got theirs and are still going to be getting it. The smartest people we know were engaged in long-term funding by the NIH and never foresaw the consequences of cheap PhD students and Postdocs (funded by government money) eventually wanting similar jobs. Too bad a scientist doesn’t retire at 63 because he hasn’t been lifting heavy loads for half his life, now they are still getting the grants while young scientists are trying to get RO1s alongside them (ESI and all that too) while also paying for social security benefits of the old as well. In a country where Food Stamps gets a budget almost 2.5 times the NIH budget, we all lose. Everywhere a young scientist turns the aged, smartest people we know have left us in the cold. How often was a noble prize given for work done by someone in their 70s?

Seriously. If people do their best work before 40, why are we funding 70 year olds at all?

It would be interesting to compare the rejection rate for R01 grants by age, and especially how that has changed. Are young investigators being rejected at higher rates or are they just not submitting grant application as much?

Since this is the product of peer review, I wonder if there is any correlation with age of the peer reviewers? It would be an interesting experiment to assemble a shadow study section composed of 30-somethings and have them review the same stack of applications as a normal study section. As a 40-something peer reviewer a long time ago, I remember three instances where I felt at odds with the study section as a whole. One was a young investigator whose grant was trashed because the assigned reviewers didn’t really understand it; one was a senior, funded investigator whose proposal I thought was quite dull; and the last was a senior, very well funded investigator whose application had only 5% of his own effort and NO experienced postdoc involvement, only tbn grad students. There was also a 72-year old whose application blew me out of the water with its excellence.

Lately many medical schools have begun hiring a lot of MD faculty that are not expected to become R01 funded investigators, but rather are there to make clinical revenue for the schools (“triple tread is dead”). They usually burn out or get smarter within a decade, and then leave to make a lot more money for themselves in private practice. I wonder how much the overall picture, trends and averages are influenced by this increasing group of non-investigator young faculty.

Similarly, there is no doubt that in 1980 it was a lot more likely that a highly talented (competitive) young Ph.D. would seek a faculty position rather than industry/biotech. Now it is the opposite and rare to see a really talented young Ph.D. trying to get into the extremely unattractive working conditions that are offered by todays academic research environment. Is that part of the reason that so few young faculty can break into R01 even though they get breaks both at, and after, reviews (at least I always give them a few breaks on the score, for their lack of experience).

I am concerned about the low number of young investigators who are receiving grant support in the form of an R01. I support a lab with a number of young investigators with one young computer scientist who submitted a tool development grant to investigate schizophrenia and his score was in the 20th percentile with the resubmission and was even selected to go to council as he was both a new investigator and an early investigator and it was not selected for funding. I have now resorted to training MDs and PhDs from foreign countries who are willing to pay for them to come be trained in my lab. Of 14 post-docs over a 3 year period, none were from the US. This is disheartening but it is no surprise really — my young investigators, some of whom are now Assistant Professors, and just not getting funded despite the fact that they are well published and in a first rate institution doing excellent science. I am at a loss to know what to do — also a second submission just does not seem to work for this young cohort or for older scientists —

It is an impressive system that can be responsive to such requests.

Is it possible that RO1 aquisition has become more competitive, and that the process of conceiving, writing, and winning for a very, very good RO1 is harder now than before? Are there many more applicants in the 35-45 year old pool than before? I am forming an opinion that Medical Schools are hiring young potential RO1 winners, as “soft money” faculty, then culling based on this competition. I don’t think this is a good thing, but hear of it anectodotally from more persons than ever before.

Your presentation of this problem is quite late. The data cited for showing the equity between male and female investigators as a function of age for different grants contained all of this information, i.e. Sex Differences in Application, Success and Funding Rates for NIH Extramural Programs,k JR Pohihaus, et al (2011) Academic Medicine, 86(6). Data analyzed was collected from the 2008 Competing NIH applications and awards. It showed

Grant Mechanism Ave Age

R03 44-45

R21 46-47

R01 48-50

P01 56-57

In summary I don’t know how young,very bright investigators can begin to succeed as a researcher now! I suspect there is significant age bias in standing study sections as certainly the R03 grants should be heavily populated by much younger investigators. R21 funding should be very similar, but it is clear that given the paucity of R01s, many senior investigators can find funding only in R21 review groups. Given that academic promotion beyond the assistant professor level is highly dependent on having a R01, many young scientists will be falling out of academia.

I understand the impulse of young struggling scientist to say “kick out the old, so I can get funded”. But look at the data and try to understand what it means. About 7% of all R01 grants are held by people age 66 or older. If you took away all the grants from anybody 66 years or older (that is, if they got a 5 year grant at age 62 we still stop it on their 66’th birthday), you could increase funding for the rest by a little over 7% – would that solve the (or any) problem? One thing that my years in science have taught me is that if you want to solve a problem, you first have to identify its sources. Old people having grants is not the main reason young people are having a hard time getting funded.

66 is ancient. The average first age is now what, 43? This is a broken system.

Those over 50 “grew up” in a system that reward and celebrated young talent to a degree that is incomprehensible now. Over all, they have not left science as they found it: they have consumed all the resources.

This graph (and there are others one can dig up) shows that it’s not just a matter of %:

http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/intersection/files/2009/12/NIH_grants_age.gif

One should remember that we are talking averages not medians when the “age of first R01” is discussed. You can see that in 1980 the age distribution was skewed to a younger age. The reason for this is that if someone was born after World War II they had a greater chance of going to college and then on to medical school or to graduate school. So there just wasn’t many 50+ year old scientist to write grants. In the 1980’s, postdoc were typically 3 years, and most good training programs insisted that trainees started writing grants in their first or second year of their fellowship. Now it is not unheard of some taking 6 years and completing 2 postdoc’s and never submitting a grant as a principal investigator. Having a lot of postdoc do all the work helps older scientists who are writing grants all the time (and need postdoc’s to get the work done). One possible solution is to have Universities develop better postdoctoral training programs that teach grant writing and have postdoc submit grants.

NIH used to have a grant mechanism they used called the R29. It was an award that could only be given to young investigators. Did ending that mechanism also contribute to this? I believe it was late 80s or early 90s those ended. Perhaps they should bring those back, if they are really serious about getting more young scientists funded.

That being said, I hope that we will always see grants funded with the greater emphasis being on the merits of the science, rather than any demographic criteria.

I wonder what would happen if grants were reviewed without any personal or institutional information being attached? No “past laurel” points given, no points taken off for being at a “lower tier” institution, no points added or subtracted for any demographic information. Based purely on the scope of work, how would a project be judged?

The reason R29 were stopped was because these investigators did not go on to get R01’s (i.e. the next step). Therefore most institutes have a policy of funding PI’s that are within 10 yrs of their terminal degree and not previously received an award. In some institutes these “early investigators” can have score that are 5 percentiles above the regular payline. That if some has not had a grant they can score at 19% as compared to the normal 14% payline.

I don’t think there is any great conspiracy against young scientists. Maybe it’s because I’ve been on plenty of study sections and not seen an obvious bias toward the younger applicants… maybe it’s because I’ve been well funded for 10 years, even though I’m only 43 and not a white male. (Caveat: remember that pay lines were much more generous 10 years ago!)

What I /have/ seen is a bias toward well written grants and against poorly written grants. A successful senior scientist just knows how to write a grant well, and there is nothing sinister about that. A well written grant is properly justified, easy to follow, and well supported with work-arounds for anticipated setbacks. I honestly do not think it’s cronies supporting one another. Do “big names” sway people? Maybe a little, but it’s not much. I’ve seen big names get well written grants funded and poorly written grants shot down, just like the junior guys. (I’ve also seen big names try to get their third or fourth R01 with their subordinate research scientist as head PI, which doesn’t go over well. This probably counts as a bias against young people in the NIH’s analysis, but that’s not a good interpretation of those particular occurrences!)

The best advice I can give a junior scientist is to serve on a study section. If you aren’t comfortable volunteering, ask your grad or postdoc advisor to recommend you to the right people. Serving will show you the difference between a well written grant and a poor one. It will teach you the process from the inside, like the important fact that you only have ~20 min to convince someone that your idea is really important. Then, take a very honest eye to your last proposal. What are the short comings? If the “stupid” study section didn’t understand your “brilliant” idea, it’s /your/ fault. You didn’t properly explain why your goals are so important and how your approach is revolutionary. It’s your job to sell your science. It doesn’t hurt to have nice figures and avoid crowding the page with too much tightly packed text.

Last, but not least, there is always the most disheartening kiss of death: maybe there is nothing wrong with your idea, but it’s just not as exciting as someone else’s. With poor pay lines, a good idea isn’t enough. It has to be a great idea. From my experience, only half the good ideas are being funded in the end. Think about it. Our junior PIs were likely great students who found it easy to get an A, easy to make the top 10%, but the competition isn’t average anymore. Maybe now they’re getting Bs, and that’s just not good enough in this funding climate. That’s hard to understand and even harder to correct.

I couldn’t agree more. But as funding increasingly tightens, we’ll be funding for the best grant writers and not necessarily the best scientists.

the best grant writers and not necessarily the best scientists.

Those who can set out a research question that is significant, with high relevance to public health, design a research plan for attacking key questions in an efficient and productive manner ARE “the best scientists”. Also, so are those who have demonstrated they can deploy their resources, direct junior scientists, establish and nurture collaborations in the service of generating scientific papers.

Unsurprisingly, people that can do that are pretty handy writing grants as well.

This notion of the brilliant scientist who cannot write a grant properly is a woeful misrepresentation of a tiny minority at best and an utter fantasy at worst.

And the idea that somehow all the best scientists suddenly got older and the new generation can’t hack it is a worse fantasy.

It’s the rationalization of the death of American science.

The best advice I can give a junior scientist is to serve on a study section.

I hear this advice all the time. Yet the process of getting on study section seems a bit hazy. NIH people have told me not to bother unless I already have an R01(or two).

Have you tried the Center for Scientific Review’s new Early Career Reviewer Program?

I guess not too early because you have to already be an Assnt Prof/PI to apply for this?

This seems to be the rub with a lot of Early Career stuff. Senior postdocs need not apply. Not sure if that’s the best cut off given the issues outlines in this and similar posts. Seems like that policy lessens the effectiveness of “Early” Career programs.

Oh, yes, for sure. A bunch of disgruntled post-docs reviewing grants is just what we need, Barkley. Maybe some graduate students too?

/end sarcasm

Look, Assistant Professors should be getting their labs going, publishing papers and, yes, applying for research funding. Not screwing around with their age-discrimination agenda on study sections…..

Interesting – now it is accepted (acutally Hip) to be predacuous (and even discriminate against) successful, productive old investigators (that should apparently slip quietly into the night and quit draining the $$$) that have survived many many very negative funding cycles through rich and poor times because they are old and thus obviously dead wood (my grant years are 31 & 22) – in favor of new blood that will resolve all issues. An equal shot seems totally fair and my old money and long term experience (I have been on over 30 study sections) does give me an edge and anyone that thinks old grants are not and have not always been pregidice against needs to see some review on the topic, but these responses seem a little biased to the premis that – old and continuously successful is always inherently bad and evil and should be eliminated because young and fresh is always better, may need a reality check – some old senile scientists are actually competitive and more and just because your are old and have been wildly successful for many cycles does not automatically mean that you are brain dead and should retire. The quality of the science is still the key and new or old should not automatically be the overriding factor. For years, young blood has been fighting an uphill run – but switching it to old blood seems a little biased.

Quoted from: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/new_investigators/

“Policy changes adopted in 2007 and in subsequent years have substantially increased the number and the percentage of competing R01 awards going to New Investigators. In 2006, 1,362 New Investigators received R01 awards amounting to 23.9 percent of all competing R01s. By 2010, the 2,091 New Investigators constituted 31.8 percent of all competing R01s. In spite of substantial increases in both the number and percentage of New Investigators, the average age at first award has not decreased. ”

By the way, the percentage of new investigators receiving awards has been relatively constant at ~25% since 1985, as can be seen from the second slide in the powerpoint file at this site: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/new_investigators/#data. There was a decrease in percentage of new investigators during the 1970’s to early 1980’s (from ~35% to ~25%), but this is consistent with the increasing numbers of grants awarded in a time of increasing NIH budgets coupled with increasing sizes of faculties. Both of these trends have reversed and, in my opinion, are unlikely to change for the better — ever.

So, NIH has a clearly stated policy that requires a bias in favor of new investigators. Thus, I’d say we need to look elsewhere to find the reason for the increasing age of the first award. My hunch is that the answer is in the ratio between number of PhDs and number of positions available — in my experience, institutions now only hire candidates with quite long track records. Hiring committees can afford to be picky because there are typically several hundred applicants for each job. (Geez, I get 150 applications for a postdoc!) Despite this seemingly rigorous selectivity, however, a large fraction of new PIs who succeed in getting a first grant fail to ever get a second grant. Where do these PIs go? Has the initial NIH funding been productive? Finally, is there any evidence that the current age distribution of PIs actually affects (either positively or negatively) the productivity and innovation of the NIH-supported research enterprise?

First some background: I am faculty at a small, teaching-intensive state school with moderate to poor internal support of research (depending primarily upon fluctuating state funds). I started as an Assistant Professor at age 31 and got my first external grant from a private foundation in my second year as a faculty member. Though funded for most of my career, I didn’t get my first NIH grant (an R21) until I was 38 and my first R01 was awarded last year at age 47. I have served as a grant reviewer for USDA, NIH and several private and European state funding organizations for the last 15 years.

As a reviewer I have not seen any evidence of age bias but a GREAT emphasis on issues related to grantsmanship. I have watched several young colleagues at my own and other institutions fail to secure extramural funding and, thus, fail to be awarded tenure. The MOST common mistake they made was not taking full advantage of help from more experienced, grant-funded senior colleagues. In some cases, the junior faculty failed to or were unable to find a mentor who could review their grants. In at least one other case, the junior faculty member was clearly the victim of undeserved negative bias that was initiated by a more senior competitor in their research field. However, in most cases, the junior faculty members involved repeatedly ignored advice/constructive criticism from those with more grant funding and review experience. One of the most oft repeated expressions I have heard expressed by new investigators after failed grant attempts is some variation on “the study section members are biased/stupid/lazy…”. Although reviewers are sometimes one (or more) of these things, most are over-worked, dedicated individuals who are really trying to pick the best science – which is an extremely difficult job when you are asked to “prioritize” the top 25% of the grants. It is the job of the grant writer to make it as easy as possible for a reviewer to be their advocate. So, what do I suggest to my younger colleagues, particularly those that may not be able to get on an NIH study section?

i) find at least two mentors with a significant grant funding history who are willing to read your grants and provide honest criticism. One should be in your field and one (or more) outside of it. Having a skilled scientist outside your field pre-review your grants is ESSENTIAL! Someone in your field may already understand much of your rationale, someone outside your area depends upon you to explain it well enough that they can understand it. Although R01 sections tend to be focused on specific disciplines, study sections for smaller grants and those at other agencies may have to cover a broader range of expertise with a smaller number of panel members – thus, not all of your reviewers will necessarily be experts in what you do. It is critical that you give these folks a reason to be your advocate!

ii) Listen to and implement the advice of your mentors. It does absolutely no good to have an experienced person comment on your grant and then ignore them. This can involve swallowing some pride – but it is more important to be successful than “right” all the time.

iii) Start your grant early and avoid the “throw a bunch of stuff against the wall until something sticks” urge. Given how competitive the funding situation is, it is better to submit one or two excellent grants a year than 5 poor ones. You don’t want to make the reviewers mad – and most reviewers get irritated when they have to repeatedly review poorly written, confusing grants authored by the same person. It is also CRITICAL to get your finished grant to your mentors/pre-reviewers well before (ie. at least 3 weeks) the grant deadline. It is difficult to do a cogent, thoughtful pre-review in 24-48 hours. I suggest that our young faculty have a polished final draft of the abstract, aims and research plan ready for internal review at least one month before the deadline. This allows the mentors/pre-reviewers time to read, think, and submit comments. After the applicant revises the grant, they should submit it back to the pre-reviewers for a final check before it goes out. The final check is important because it is easy for the applicant to introduce additional problems when they revise the proposal.

iv) If you get an unfavorable review back – get mad for a few days. Then, let your mentors/colleagues also read the review (and the original grant as well). This can be embarassing but experienced reviewers can sometimes help you read between the lines and give you a different (and useful) perspective. Also contact your SRO for advice – mine have been very helpful to me.

vi) Establish an internal pre-review panel at your institution composed of experienced grant writers and reviewers if you don’t already have one. If you have one, use it! This may not be possible because folks have so much to do, but where possible, it can be very useful.

vii) Insist that your Ph.D. program (if you are at an institution that has one) has a serious emphasis on student grant writing. In ours, most students write at last two NIH style proposals (an R03 during an advanced course and an R01 as their qualifying exam). Students are also encouraged to compete for local, state and national graduate student research grants. This may not help current young faculty get funded but may help the next generation.

Hope this helps for your next application:)!

That was very useful tips, oldtownfan! But I am facing other problems and feel that the scientific community is not that open as it should be to young scientists like me. Granted that I do not have that much networking in US since I finished my graduate studies in Europe and just moved here for postdoc and then had to move to a – let’s say – not so happening capital city of a famous state. I have been trying to contact (shooting out emails) potential mentors long before my move to this city and asking them whether they would be willing to help me in applying for grants and give me chance to meet them and discuss the projects that I want to work on in their lab! So far no replies to my email. I still keep on writing to people explaining to them the projects that I am interested in, their impact on public health and how I want a position and therefor their help so as to apply for external funding. I see that to apply for NIH and almost any grants, one has to have a independent research position at an institution which does not seem to work in my case (at least in the city that I am in unless one has very good connections). I am frustrated and does not really have a clue right now what I can do to better my chances in order to become an independent researcher. I have been also applying to colleges and schools in the vicinity so that a PI equivalent position there will give me opportunity to apply for external funds and establish myself. I might be still in the learning curve but I am the person who wants to keep the learning process go on till I die, but I believe that I am good enough to do sound scientific research. During my graduate studies, we did have grant writing exercises and I had been complimented by my professor that I should try to become an editor and review the scientific publications (just trying to blow my horn a bit!). Would appreciate any ideas that I can put to use!

Dear Dr. Rockey: I would like to comment on the pool of PIs who are over 55-60 year old and need to compete for NIH funding, or enter the funding arena. I suppose that many of these PIs are Green Card holders or recent US citizens. Back and forward from Europe to the US for years I have been writing grants for other PIs who were established at top Institutions, and I was able to be paid as a Visiting Scientist. This humiliating saga of foreign investigators who write for established investigators in research/academic institutions is well known. Now, even if I worked almost an entire life time, thanks also to the NIH grant that I got, I hold a faculty position myself, yet I have not worked enough as a faculty to gather enough benefits and save for my retirement. The stress continues. I think that the NIH should create a funding mechanism that protects scientists like myself from the risk of age discrimination. We can’t even think of retiring from science for two reasons: on one hand we are proud to have finally our independent labs and on the other hand we will not be able to survive out of scanty retirement savings.

Thank you in advance for your attention

I have been wondering why study sections use new reviewers on resubmissions. My understanding and many others is that in the peer review process an applicant receives a critique. In their resubmission, they answer X,Y,Z of the critique. If they satisfactorily answer X,Y,Z and especially include new data that supports the hypothesis, the score should improve. However, this does not happen when new reviewers are brought in for the resubmission, since the new reviewers are not constrained by the previous review and can include additional critiques that were never an issue in the first review. In the case of early/young investigators, just this variable can sink an entire research project that was considered exciting by the first reviewers. If the same set of reviewers are used for resubmission, then the process would have less variability that would result in a fairer review. At the moment, it seems like the luck of the draw with huge consequences. Unlike many established investigators, young investigators do not have a trove of data to choose from for another project. It may take them months to years to collect another set of preliminary data, and this is the reason that I think it is taking longer for the first funded R01. Is it that difficult to call back reviewers that have rolled off study section to ad hoc for a resubmission that they previously reviewed?

RC you are very seriously mistaken about the process. The short version is that your grant is in competition with what is under consideration for that specific round. Improvement over past versions can result in worsening scores if the other grants submitted that next round are all much better.

Sorry for being late to this post, but when I see the AAMC data, I wonder if we’re missing a silver lining that might be useful in advocating for sustainable increases from Congress. The age distribution shows that we have almost a perfect distribution of PIs in the prime of their scientific careers. As demographics shift naturally with the aging of the boomers, we might never again have such a large and productive research workforce in the prime of their careers. Keeping the pipeline for future researchers is definitely important. But I hope we as a country do not miss an opportunity to capitalize on the enormous wealth of intelligence in the current workforce. Yes – we should ensure that the future of the research enterprise is strong – and NIH and community efforts to get R01s to young PIs before they exit the pipeline are essential. But perhaps we’re missing a strong piece of advocacy – the U.S. has the strongest scientific workforces in the world, the majority of whom are in the prime of their careers. NOW IS ABSOLUTELY NOT THE TIME TO CUT FUNDING (sorry for yelling).

Is there any data available regarding how many NIH investigators actually have medical training as opposed to those who just have a PhD?

There is historical data on funding by degree on RePORT, as discussed in other Rock Talk blog posts (for example, “Does your degree matter?“)

I am curious what is the success rate for PI by age?