56 Comments

The R01 (or R01-equivalent) grant has traditionally been a critical component to the launch of one’s research career. A number of academic leaders have described and expressed concerns about the age at which scientists are first supported on an R01 award (“age at first R01”). The biomedical research workforce is aging over the past several decades due to demographic trends and the end of mandatory retirement in academia. Difficulties faced by early-career investigators may include prolonged training, advantages of incumbency, and cost-shifting to universities.

We have heard these concerns too, and recognize the potential impact on the future biomedical workforce. That is one of the reasons why, in the late 2000’s, we implemented an Early-Stage Investigator policy And, after considering recommendations from the Advisory Committee to the Director (ACD) and the National Academies of Sciences, NIH has over the past few years implemented its Next Generation Researchers’ Initiative. NIH is funding record numbers of early stage investigators. We recently published data showing that long-term career stage trends may have stabilized.

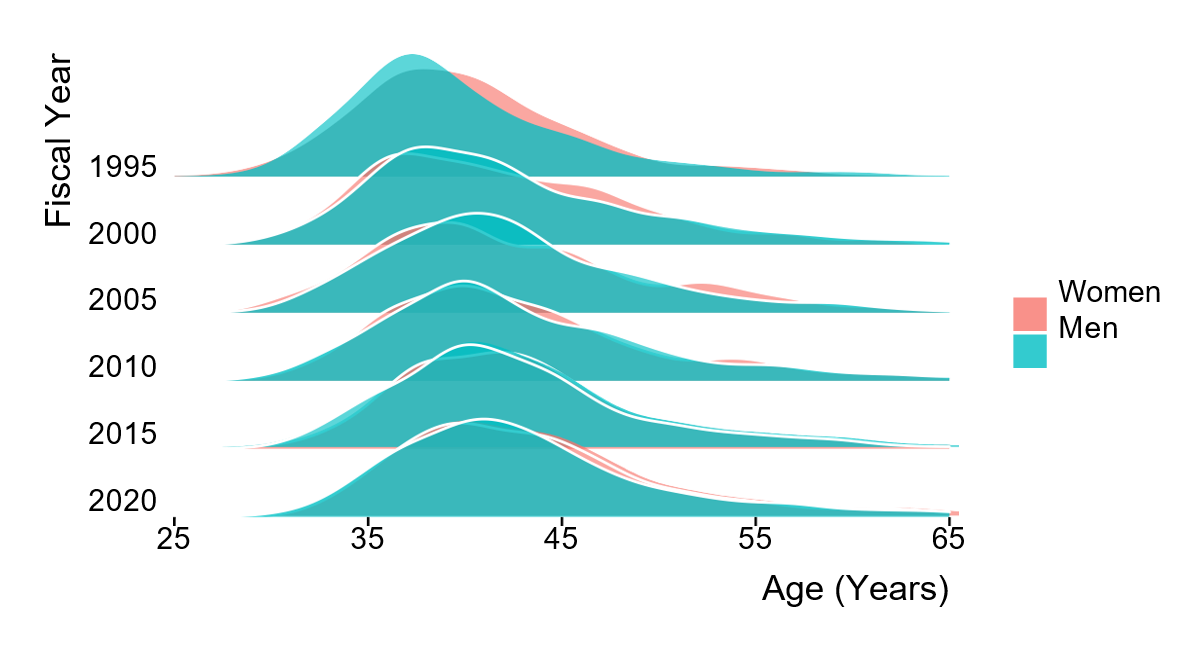

Here we present data from fiscal years 1995 to 2020 on age at first R01-equivalent grant. Tables 1 and 2 and Figure 1 show secular trends for age distributions according to gender. There are no differences between men and women. While age has been continuously increasing, the rate of increase has slowed over the last 10 years.

Table 1: Age at receiving support on a first NIH R01 award for Principal Investigators self-identifying as men according fiscal year.

| Fiscal Year | Number | Mean | Median | 10th Percentile | 25th Percentile | 75th Percentile | 90th Percentile |

| 1995 | 897 | 40 | 38 | 33 | 36 | 43 | 47 |

| 2000 | 1027 | 42 | 41 | 35 | 37 | 46 | 52 |

| 2005 | 933 | 42 | 41 | 35 | 38 | 46 | 51 |

| 2010 | 1259 | 43 | 41 | 35 | 38 | 47 | 53 |

| 2015 | 1032 | 43 | 42 | 35 | 38 | 46 | 52 |

| 2020 | 1342 | 44 | 42 | 36 | 39 | 47 | 54 |

Table 2: Age at receiving support on a first NIH R01 award for Principal Investigators self-identifying as women according to fiscal year.

| Fiscal Year | Number | Mean | Median | 10th Percentile | 25th Percentile | 75th Percentile | 90th Percentile |

| 1995 | 376 | 40 | 39 | 34 | 36 | 43 | 47 |

| 2000 | 411 | 42 | 41 | 34 | 37 | 46 | 50 |

| 2005 | 404 | 42 | 41 | 34 | 37 | 46 | 53 |

| 2010 | 655 | 43 | 42 | 35 | 38 | 46 | 54 |

| 2015 | 522 | 43 | 42 | 36 | 38 | 46 | 52 |

| 2020 | 1003 | 44 | 42 | 36 | 39 | 47 | 53 |

Figure 1: Gender-based distributions by fiscal year of age of Principal Investigators receiving support on NIH R01 award for the first time.

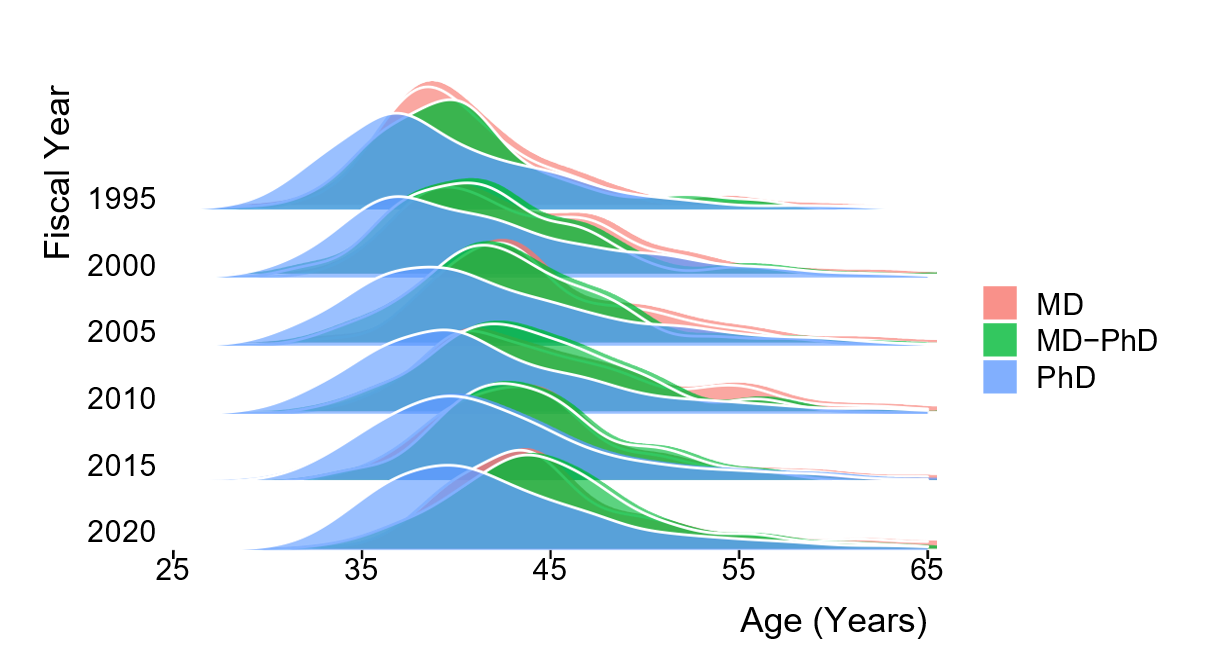

Tables 3 to 5 and Figure 2 show corresponding secular trend data according to degree; investigators with an MD degree (either alone or with a PhD) have been consistently older. It is likely that physicians may be older because of time spent in clinical training after receiving their degrees.

Table 3: Age at receiving support on a first NIH R01 award for Principal Investigators with an MD degree according to fiscal year.

| 1995 | 224 | 41 | 40 | 36 | 38 | 43 | 46 |

| 2000 | 262 | 43 | 42 | 37 | 39 | 47 | 51 |

| 2005 | 223 | 45 | 43 | 38 | 41 | 48 | 53 |

| 2010 | 282 | 46 | 44 | 38 | 40 | 50 | 56 |

| 2015 | 219 | 45 | 44 | 39 | 40 | 47 | 54 |

| 2020 | 344 | 46 | 44 | 39 | 41 | 49 | 57 |

Table 4: Age at receiving support on a first NIH R01 award for Principal Investigators with MD-PhD degrees according to fiscal year.

| 1995 | 130 | 41 | 40 | 35 | 37 | 43 | 48 |

| 2000 | 160 | 42 | 41 | 36 | 38 | 45 | 49 |

| 2005 | 162 | 43 | 42 | 37 | 40 | 46 | 49 |

| 2010 | 216 | 44 | 43 | 38 | 40 | 47 | 51 |

| 2015 | 148 | 45 | 44 | 39 | 41 | 47 | 52 |

| 2020 | 215 | 46 | 44 | 39 | 42 | 48 | 54 |

Table 5: Age at receiving support on a first NIH R01 award for Principal Investigators with a PhD degree according to fiscal year.

| Fiscal Year | Number | Mean | Median | 10th Percentile | 25th Percentile | 75th Percentile | 90th Percentile |

| 1995 | 903 | 39 | 38 | 33 | 35 | 43 | 47 |

| 2000 | 1007 | 42 | 40 | 34 | 36 | 46 | 52 |

| 2005 | 934 | 42 | 40 | 34 | 37 | 45 | 52 |

| 2010 | 1379 | 42 | 40 | 35 | 37 | 46 | 52 |

| 2015 | 1156 | 42 | 41 | 35 | 38 | 45 | 52 |

| 2020 | 1684 | 43 | 41 | 35 | 38 | 46 | 52 |

Figure 2: Degree-based distributions by fiscal year of age of Principal Investigators receiving support on NIH R01 award for the first time.

We will continue following these age-related data going forward as they help us better understand trends in the wider biomedical workforce. Iam grateful to my colleagues in the Office of Extramural Research Division of Statistical Analysis and Reporting (DSAR) for their help in conducting these analyses.

The increasing age may also be related to adults changing careers and/or starting their research careers later. Not sure if the cost of degrees may be part of the decision making by individuals to consider reducing financial burden prior to commencing their next degree or research degree.

The answer might not be as linear such as mean age across the years. Some areas of science may have much younger researchers whilst other areas may have older applicants due to knowledge, skills and how long the area of science has existed and this may change over time. Also, there may be many contributing factors and lifestyle decisions that may come into play that may not have been important or existed prior to the 21st century.

I suspect this is a contributing but insignificant factor. The greater and more likely explanation is that research dollars were far more abundant and available in 1995 compared to today. Furthermore, longer doctoral education period/post-doc fellowships are now accepted as the norm due to (1) incentive structure of the academic model to retain cheap labor and (2) the type of complex, team science today necessitates greater volume of work.

Thank you. It has oft been said that the crucial step is the second RO1. Do you comparable data on that topic?

Very good point, first R01 often is aided by an early stage investigator payline bump, second one doesn’t get that benefit. I’m also curious about data for single versus multiple PI R01s which are becoming more the norm. Do these stats include MPIs or are these single PI grants only?

Based on this data, slightly less than one quarter of new R01 recipients hold an MD or MD PhD. And a decline (5%). And they are older. Shouldn’t this be a concern?

I absolutely agree – NIH has gotten much better at supporting junior researchers (and rightly so) but once one has lost the ESI advantage getting that second R01 can be a huge challenge as one is now a junior PI competing with some very senior people.

Would be nice to know if over the same time span, the average period from submitting the first R01 application to the NoA has also increased. Perhaps some of this increase in age of the first-time R01 recipient is due to increasingly longer training periods.

You only went back to 1995. I got my Ph.D. in 1978 and had my first R01 in 1981. I was 32 years old. If you went back further I think the picture would be even more disturbing.

I completed my PhD in 2000 and continued in several postdoc positions due to funding issues in the several labs that I worked. Had to keep changing labs to keep my visa status active. This becomes a Red Flag on your CV. After 21 years of struggle, I have got a faculty position at the rank of assistant Professor. But I do not qualify as an ESI. Will I be considered a New Investigator for my first RO1 application? Are there any relaxations?

There is no benefit I have see with NI status. No real benefit to the mid career people who had none of the advantages to boost a career.

It would also be interesting to see whether funded investigators continue to receive new/continuing awards to an older age than was true 20 or 30 years ago.

It would be very interesting to add the data beginning from 1970 or 1975. My anecdotal impression is that the biggest changes were between then and the mid-1990s.

It would be interesting to know if some of these statistics are driven by people who get PhDs as second careers – entering PhD programs much later than the previous complete 4 year undergrad, then 2-3 years for masters, and then another 3-4 (or some combination of the latter 2) for the PhD. Many of the people I work with started life as clinicians in health care and then went back or are going back for PhD’s in their 30’s or sometimes even their 40’s. Did you take that into consideration?

Would be nice to see inclusion of PharmDs in the data.

MD and MD/PhDs are older than PhDs, which makes sense given training length. But also important to note that MD/PhDs and MDs are the same age. So MD/PhDs are getting funded sooner after training, and the extra time wasn’t wasted, which may be notable given some anti-MSTP push.

I am a well-established researcher, but even one R01 has been elusive. NIHFirst was not available to my generation and neither was ESI status. I became ineligible for the larger SCORE grants due to funding from other agencies. I am on my 4th round of funding from another federal agency! Latest round of NIH reviews demonstrated an elitism from the study section. I don’t have any belief that I will get a mainstream NIH award before I retire. In my view, it will require a major overhaul of how NIH reviews applications to make a dent (fundability based on recognizability is unlikely to help, perhaps NIH should go the double blind route). It would be interesting to separate out ESI from the the data above. While there is a focus on the “next generation” there is a fully functional “lost generation” that has all been ignored called “Mid Career.”

I can second pretty much all of this, though I might be a bit younger and am only on the third round of federal funding. I also remember submitting a general concept twice, having it not funded, then not being allowed to submit it again to NIH for 37 months–even with substantial changes in aims and direction.

I agree 100% with your statement, there are so many of us in the ‘lost generation’. NIH should really look at this group of scientists.

Thank you, I am the one who posted the “lost generation” point. I am grateful and happy to see that I am not alone in this “lost generation.” A comment I read also stated reviewers should be respectful of efforts. I am tired of being poo poo’d by NIH reviewers when I am able to get glowing reviews from another agency (funded by that agency for 23 years). Clearly, who you are and what institution you come from, figures into your success as well at the NIH (latest R01 reviews attest to that).

Same here! Have scored 4 federal grants, none of them an R01. No ESI advantage in my case (and I would’ve probably gotten one if that had been in place back when), and now I’m in the dead zone of not ever having had one and not having any first-timer bump.

The reason it is taking longer is the amount of data needed per paper has gone up 8-10 fold over this time frame and it takes longer to generate all these data. Young people cannot even start looking for a job until they get the big high impact paper and a couple of lesser ones. Editors of journals that want 4 papers worth of data per journal article and not limiting comments from reviewers that always ask for more data are to blame. This is what needs to change.

Amen. Couldn’t agree more! Ph.

It is not surprising the younger generations would choose not to enter this field. Most individuals do not get a decent salary or any semblance of stability until an R01. With that event not occurring until the mid-40s, it is essentially impossible to recoup the 2 decades of lost income potential compared to another career field. I currently discourage promising students from getting a PhD in biomedical research unless they are either a superstar or they are completely committed to the struggle.

I agree. Young investigators move the field forward by bringing in new ideas, but both the funding landscape and universities are dominated by a much older demographic. With the end of mandatory retirement in 1994, universities have been paying tenured professors into their 80s, exhausting resources that should be made available to a younger generation. Only superstars, or those willing to completely give up on a work-life balance, can make it in this competitive environment.

Amen

This whole article stressed me out. Why? Let’s say you go directly into a 4 year college and graduate at the age of 22 or 23. Then, immediately go into a PhD program, this is quite common in the sciences. You graduate with your PhD in, let’s be generous, 6 years; your 28 or 29. Then you enter the gray (and I mean gray, dreary, unstable, undefined) area of “post-doc”. Based on the charts above you are 47 by the time (75th percentile) you get your first R01. That is 18 YEARS of living in this gray zone. This is stressful. It’s not a position, you’re not a student; salary, health care, benefits, retirement-what is that? is all over the place! There aren’t standards, only suggested minimums; and this is supposed to be the “productive years” of your life? In what other career would you get paid, have the instability, lack of benefits, that a post-doc has after 8 years of education? The field has to create an official “post-doc” position that provides a salary sufficient for 8 years of education, stable benefits (for a family) and retirement. To add to the instability, most “post docs” are 2 (let’s say 3 because it divides into 18 evenly) years; that is 6 different post-docs in the gray zone. This is stressful.

Yes to all of what you said. I am a 4th year postdoc and I am currently staring into the black void that is my future. My wife, who has a masters and makes over 100k a year, cannot wrap her head around how someone with a Ph.D. makes as little as I do, has zero job security, and a completely uncertain future. If it was as simple as putting your head down and working hard until that R01 hits, it would not be that big of a deal, but as this article states, that may not happen soon enough to survive the academic Squid Game. I’ve already had several friends (all good scientists) leave academia as postdocs because the stress:security:pay ratio is all out of wack. I just had a ‘not discussed’ K99 (ugh) and in my field there are very few opportunities for funding outside of the NIH. I LOVE academia and research, I have 12 authorships (about to submit a 5th first-author), yet the reality is slowly sinking in that I may be shown to door in the coming years. It’s a brutal career path, that’s for sure.

I’d like to add to John’s comments above. This data is not surprising, with funding issues and training timelines being written or complained about for at least 20 years, or about the time that I started my undergraduate degree. In order to stay “in research”, I had to accelerate my PhD (~5 years) and abbreviate my postdoc years for financial reasons, eventually landing a position with grant writing/holding rights but no appointment to supervise students, which is quite fine with me as I don’t want to train additional PhDs at this point or pay staff 30-50% of what they could earn elsewhere. This will probably limit my advancement, but I will live with it for now.

In my experience, the most successful PhD/postdocs that I’ve encountered have had one or more of the following behind them, in addition to some above average level of intelligence and grit: 1) Commitment to an area of science reached to at a young age (which develops a knowledgebase usually gained much later in education), 2) One or more family members with advanced degrees (adding to #1 and also potentially opening up more educational part-time jobs), 3) Some level of family wealth to reduce the financial pain of graduate school/postdocing, or at least let them extend their training period.

These 3 points probably apply to any career path but I’m surprised at how many people early in their careers assume that the playing field is completely level.

What does the age of applicants look like over the same time period? Are people older when they first apply? And how does that look like when gender is a factor?

Can the trend in age to first R01 be correlated with inception or expansion of other grants mechanisms, like K awards. More Ks — age for 1st R01 goes up if you believe K’s lead to R’s.

Also the gender gap seems balanced, so I wonder if women were the primary respondants, e.g. for 2020, ~1000/1300, somehow skewing results. The graph makes looks the M and W overlap well

Lots of great comments. I am postdoc but didn’t receive my Ph.D. until I was 40. As others have mentioned, many people are delaying their pursuit of a Ph.D until later in life. Would love see these number adjusted for “time to receive first R01 AFTER terminal degree completion.”

This is an important point. Those who “time out” of the K award have a void of opportunities until they land their first independent position and have institutional support allowing them to apply for the R01. Can this group be supported by NIH with another mechanism/bridge? There really is no federal funding available to them, other than the R03 or R21 (if the reviewers would even consider a postdoc application for these). Cost of living often squeezes these individuals until they may be financially forced to go into another field to survive, rather than stick it out after their 6th year of postdoc – especially with the shrinkage and pullback of job opportunities at universities due to COVID and online delivery of course content. If not addressed, this may cause a major gap in scientific intellectual capabilities, especially with numbers of women with PhDs, in the near future.

Fascinating comments so far.

I think there may be story here about how long people are expected to be in the “postdoc” or similar role. I think the average duration of postdoctoral type training or equivalent in the MD route is probably longer now. On the PhD side – this may be related to the lack of mandatory retirement at 65, as older PIs want to keep their trained postdocs in that stage as long as possible. Unfortunately – this means that one is expected to continue on “training” and making very little pay for very extended amounts of time.

I’ve often wondered if a “double blind” study review would be a good idea. I don’t think its possible to remove the last names given that these are listed within the references & publications. It might be possible to remove university affiliation, gender, or other factors that would contribute to biased reviews as mentioned in comments here.

As a female investigator – I find it encouraging that the total number of R01s has increased for women over time, though I am not sure if the total number reflects the actual total number of awards given to investigators or only those who participated in this study.

This analysis is missing an extremely important point:

Whether someone gets an R01 at any given age, whether they get a second one, or what kind of educ/prep they have, IS INSIGNIFICANT compared to the issue of whether anyone can make a career out of getting successive R01s. A few can, but do the math – the majority cannot. The system does not do that, the system cannot do that. NIH trains, but they won’t support those whom they’ve trained. And that’s what the generation of potential scientists sees. They’re smart – they decide early on that the career of a biomedical scientist is a very bad bet, and they opt for other things.

You can make the argument that NIH is funding/supporting the best and the brightest, but only the best and brightest among those who apply. I am part of the some of the best grad programs in the country, and the quality of applicants has dwindled dramatically over 20 years. Back when I started, we wouldn’t have even considered someone from a small “nuturing” college with a 3.3 GPA and mediocre-quality research experience. Now, that’s our core group. We used to recruit only men into our programs, now we have only women. Is that progress?

Has anyone else gotten an R01 critique back lately where the most serious criticisms are “unclear whether this will be successful”, “risky”, “the applicant provides no evidence that this can be done”. Hey folks, they’re called “experiments”!

Have any of you tried to recruit post-docs lately? Good luck.

Regarding, ” That is one of the reasons why, in the late 2000’s, we implemented an Early-Stage Investigator policy”, can you tell if it made a difference? I am not convinced that just reducing the payline for ESLs is targeting any meaningful covariate. You do have access to covariates to take a deeper look that we outside the NIH cannot access via the Reporter API. What variable(s) do you find best explains age at first R01 award? How have you targeted that specific variable?

I have written three successful R01 grants so far–all under someone else’s name. The first one, my PI came to me and asked what I put in the grant because it got a good score. (He hadn’t even read it before it was submitted.) That grant was funded. The second one, I submitted under my name and it wasn’t even scored. I then resubmitted it with someone else as PI and it got a 4th percentile and was funded. The third successful grant, also submitted under my PI’s name, got a 1st percentile and was funded. I can’t get an independent position because I don’t have my own funding and maybe seen as too old for assistant professor positions. I clearly have good ideas, but the PI matters a lot to the grant review committees.

I believe you! But, there is an important thing to consider …

I’ve spent over 12 years on various study sections, and the most incredible thing I have observed is that ONE person can utterly kill a grant, but one person cannot make a grant succeed. That’s the natural consequence of assigning 3 reviewers who determine the “range” of scores in which other panel members are likely to vote. When we review 50 proposals and know that only 5 are going to be funded, it is only natural to reserve your best scores for people whom you know will put that funding to good use by performing good experiments, publishing good papers, being a good collaborator, and training good students. It doesn’t matter what the proposal is – out of any group of 50 proposals, you are going to have at least 5 with that reputation, and it really doesn’t matter much what they write in their proposal. On one hand that’s outrageous, but on the other hand – there’s nothing in the world wrong with funding those 5. The problem comes with not funding the other 45!!! And here are the ways that NIH creates this problem: (a) Awards more than one R01 to some investigators, (b) Creates an institutional appetite for faculty who can get more than one R01 at a time, (c) NIH trains far more people than it can support, and (d) NIH baits young investigators with a very slightly easier first R01 only to KILL them dead, discouraged, and untenured when they go for their second.

I think it might be important to study individuals who have multiple R01s for several years and how this fact might make a big difference in how soon or how many R01s people can get. I also would like to see a table that accounts for race and ethnicity.

It would be great if we could see these same age data based on whether investigators decided to have children

What do the Age of First R01equiv trends look like when stratified by the race / ethnicity of the PI?

The most egregious omission is how many people at what age did NOT get an RO1. And also the number of proposals that were not funded at certain ages. Has the age of failure changed over time? How many fails does it take to win an RO1 and at what age, or more importantly the number of applications? Negative data will also reveal other trends. And please go back to the 1980s to see the real trends. Science had already become an old boys club by 1995.

It would also be interesting to know what is the average age of an investigator when they get their last NIH R01 grant. If one doesn’t get to start their professional career (defined as first R01) until 44 years of age and one assumes an average retirement age of say 67, and one assumes that productivity and thus competitiveness is much lower close to retirement, the window of opportunity for one to practice being an independent R01-funded scientist is frankly scarily fleeting relative to the years of training and relative to other professions.

I am an nih funded MD researcher who is mid career. I tell trainees not to choose this route unless they can’t imagine doing anything else. It’s a ton of sacrifice, and yes the pay has not kept pace but this is not why I chose this career path. Unfortunately, what is killing my joy is that the amount of paperwork involved with any research project has tripled during my career. I hired someone just to keep up with all of the regulatory paperwork that is constantly growing. Also, reviewers are unnecessary nasty on study sections. Let’s be respectful of one another’s hard work. It would be helpful if reviewers received coaching on how to provide constructive critiques instead of fixating on minutiae and demanding an ungodly amount of data that is not realistic when someone is starting out or has a small lab. I’m also sick of hearing “Dr. God is an outstanding scientist; even though the details aren’t here, I know he will get the work done and find something interesting.” We who serve on study sections are guilty of perpetuating this problem of not drawing the next generation of physician scientists in.

This data seems very important for university promotion and tenure practices because of the fact that it is difficult to get promoted in many schools without an R01, Is there any analogous data on time in faculty role to first R01?

I am wondering why age is an issue? Are R-01’s considered on an age basis? It should not matter.

There are still differences in number of awards between men and women. Why were these data not analysed?

Further subanalyses would be useful.

many thanks!

The data for participants identifying as women suggest bi- or tri-modal distributions that persist across time. Is there any insight into what is driving this separation?

May be less accessible in the database, but perhaps look at age at first R01 submission and first R01 receipt. This would help distinguish those just getting in the game at a later age and those who, like I, had years of failed attempts at R01 funding before receiving the first one. It’s all tied together as the “longer training periods” are in some sense a response to the difficulty in getting independent funding.

One problem is that the leadership of the NIH both (a) follows the bad example of influential politicians (D & R) who stay in office as long as they are still breathing; and (b) sets a bad example itself for the biomedical research community, by allowing directors of NIH ICs to hold their positions into their 80’s. This is bad policy, period. U.S. presidents are limited to two 4-year terms and so should NIH IC directors. Look in the mirror, NIH leadership.

A larger problem is the following question: What percentage of Ph.D. graduates in the biomedical sciences ever end up in a position to pursue their own original research ideas that address the mandate of the NIH? What is the point of training so many Ph.D. graduates if vanishingly few of them get to formulate and pursue their own original research ideas? Most don’t even get to try and fail at peer-review, and even for those who “fail” at peer-review, what does that say about their “training” (or peer-review)?

The NIH should work with other levels of government and private industry to create a national network of well-equipped academia-independent biomedical incubator facilities for startups founded by graduates in the biomedical sciences who do not have a tenure-track faculty appointment. More shots on goal by more players leads to a better team outcome.

The NIH’s current SBIR/STTR program is almost exclusively focused on the 1-percenters of biomedical Ph.D. holders who have tenure-track faculty positions and can lease suitable wet-lab space from their institution for a Phase I SBIR/STTR. Academic medical centers won’t lease their currently unused (and NIH-funded by F&A costs) lab space to unaffiliated but qualified SBIR applicants because the former have a conflict-of-interest (the institution can’t claim the IP developed by the unaffiliated SBIR applicant). Many parts of the country have no alternative biomedical incubator wet-lab space for short-term lease (e.g., for an SBIR Phase I).

I’d also say that the overwhelming majority of NIH SBIR funds do not go to startups. They go to established “small” companies, which can have up to 500 employees. Across all USG agencies with SBIR/STTR funding programs, I’d say < 10% goes to startups. That's < 10% of $3B/yr. or < $300M/yr. for startups, from all USG agencies offering SBIRs. That's peanuts, really.

Seems like it would be interesting to investigate ethnicity)submission v success) and successful candidates displayed by ethnicity. Considering the conversations about race in this country, this would be a timely study. Great work!

Thanks for the data. No surprises here. Studies show that nearly every step in the physician-scientist pipeline is taking longer than it used to (see the NIH Physician-Scientist Workforce Report and the AAMC National MD/PhD Program Outcomes Study). The time to degree in MD/PhD programs is longer than it used to be. The time spent after completion of postgraduate clinical training until a first job is also taking longer and often includes 1 or more years of “no longer a fellow, but not a faculty member yet”. An additional contributor to increasing age at first job and age at first R01 is that there has been a big increase in the prevalence of time gaps between college and medical school. Gap prevalence has increased for MD students, but has increased even more for MD/PhD students. A recent study overseen by several of us connected with MD/PhD programs (Myles Akabas at AECOM, Reiko Fitzsmonds at Yale and (me) at U Penn) in behalf of the national association of MD/PhD programs shows that in the class entering MD/PhD programs in 2020, approx 75% of the matriculants had taken gaps of 1 or more years. That’s up from 53% in 2013. Although gaps are usually spent doing research, investment in these gaps has not paid off with a shorter time to degree, so age at first R01 continue to drift upwards. Time to shorten the career path and let them get to work in behalf of all of us that much sooner.

Skip, I really appreciate your comments here for the MD/PhDs out there. Especially:

The time spent after completion of postgraduate clinical training until a first job is also taking longer and often includes 1 or more years of “no longer a fellow, but not a faculty member yet”.

I felt blindsided by the prevalence of “clinical instructor” or other “fund yourself because the institution is not quite ready to invest in you yet” roles across top universities. In very best-case scenarios people were in these roles for a year, in most cases it was 3-4 years. After residency, I felt pressured to train more as both a fellow and a postdoc (I was 36 post-residency). My personal calculus was around what I would be spending my next 5 years doing in academia. I had hoped to be independently pursuing the questions I had formulated during my training at that point. However, I found that in order to get an R25 and apply for a K08 (both mentored training awards), I’d have to align with existing research programs that would get me to career endpoints rather than independently design exciting projects. I was hoping to get an R01 at 40 in a best-case scenario, which would be quite ahead of what is described in this article, but still felt too late. Given the long lead time into an R01, what I heard repeatedly across institutions was the only way to really have your career take off was to get a private transition to independence award or to connect with the right folks to be gifted a generous endowment. This all felt very constraining, to the point that I looked at non-academic opportunities and found better fits.

Anyhow, throughout my MD/PhD training and residency, I had not expected to leave academia at this point in my career. Now, as I advise younger trainees, I try to help them envision what life looks like as far as post-residency. I feel like NIH data do not capture key data, such as post-residency roles (fellow, clinical instructor, etc.), post-K08 routes (staying in academic research vs going into practice vs industry), and whether physician-scientists stay long enough to get the first or, perhaps most importantly (as pointed out above), the second R01. In my personal experience, about 1/10 people matriculating into MD/PhD programs gets to the 2nd R01 in academia. The rest go off to other things before that point.

But I’d love to see something from the NIH like survival curve data split by decade starting in the 1970s to 2000s with second R01 as an outcome. Though we may not have much from the 2000s (as we can appreciate from this article it may take 25+ years on average to realize that data point for physician-scientists), the NIH is the only organization that can collect this information in a reliable manner.

Senior researchers have a clear advantage, but also the greater pressure from their institutions to rack up multiple R01s each year at every cycle. Once a person gets that kind of momentum, it is extremely hard to compete with the PI who is flush with cash, staff, and a steady stream of pubs (even those that are still gifted to them). At every turn, they hold a substantial advantage. It is not the weaknesses of the early PIs that is the problem, it is the overwhelming strengths and cumulative advantages of those holding multiple R01s. We should be encouraging institutions to have their senior PIs transition to mentorship roles. You can easily set up a system by which traditionally successful PIs are penalized by not being mentors more often or by making the grants other than R01 more attractive to both them and to their institutions who are pushing them to submit R01s in a machine-like manner. We need better carrots and better sticks for our most successful researchers who often love and thrive being mentors. Give them every reason to chose that route by their 3rd R01. These are proven leaders, now show that you can make new leaders and not just lead more followers. Do not let up on them. They can clearly produce and we are underutilizing our best resources when we simply relegate them to submitting R01s rather than mentoring future leaders.

As the life span increases the trend is for the elderly to be more productive. what is the maximum age for a funded researcher

Hi. I am 72 years old and I was just awarded my first NIH research grant (a SBIR Fast Track – Phase I/II) for $2.5M. I was wondering if there is any information available about the oldest PI to get a first time grant. Thanks.

In what other career would you get paid, have the instability, lack of benefits, that a post-doc has after 8 years of education? The field has to create an official “post-doc” position that provides a salary sufficient for 8 years of education, stable benefits (for a family) and retirement. To add to the instability, most “post docs” are 2 (let’s say 3 because it divides into 18 evenly) years; that is 6 different post-docs in the gray zone. This is stressful.