83 Comments

Last September, and in January of this year, we wrote about a suite of initiatives aimed at improving the quality and transparency of the NIH-supported research that most directly engages human participants – clinical trials. These initiatives include dedicated funding opportunity announcements for clinical trials, Good Clinical Practice training, enhanced registration and results reporting on ClinicalTrials.gov, and required use of single IRBs for multi-site studies. We are now entering the final phases of implementation of these initiatives – so, if you are contemplating research involving human subjects, please read on.

We’ve received queries from members of the research community seeking clarity on whether their human subjects research will be affected by these new policies, and if so, how. So, we want to call your attention to four questions researchers involved in human studies need to ask, and answer. These questions are:

- Does the study involve human participants?

- Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention?

- Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants?

- Is the effect that will be evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome?

If the answer to all four questions is yes, then we consider your research a clinical trial.

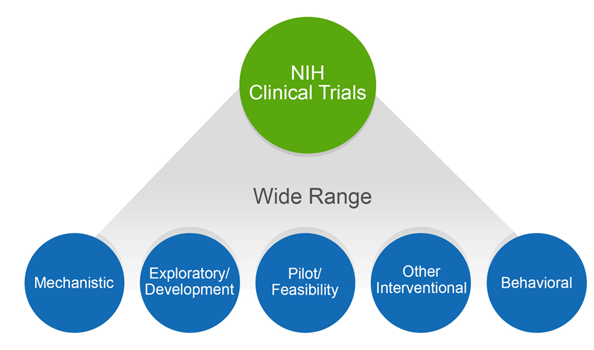

The NIH definition of a clinical trial is “a research study in which one or more human subjects are prospectively assigned to one or more interventions (which may include placebo or other control) to evaluate the effects of those interventions on health-related biomedical or behavioral outcomes”. The definition was published in 2014, after extensive public input, and affirmed, after even more public input, in our policy published in September 2016. The clinical trial definition encompasses a wide variety of study types, as shown in figure 1. These range from mechanistic studies to behavioral studies, to pilot/feasibility studies, all the way to large-scale efficacy and effectiveness trials.

The breadth of the NIH definition is intentional, given the nature of the NIH portfolio and imperatives for maximal transparency. Transparency shows respect for the participants who put their trust in us, in the face of unknown outcomes, to help advance science. Our concerns about transparency stem in part from the issues surrounding the reporting of clinical trials data. For both NIH-funded and non-NIH funded trials, unreported data and untimely dissemination of results has been documented over and over again. Others have expressed concern that the NIH has not collected needed trans-NIH data to enable it to function as proper stewards of clinical trials.

Some have argued that we should not expect trial registration and reporting for small or exploratory trials, for trials that focus on safety, or for trials that fail to meet enrollment targets. As we stated last September, NIH chose to emphasize the value of transparency for these kinds of trials as well, as “the benefits of transparency and the need to fulfill the ethical obligation to participants is as relevant to these types of trials as to any other type.” We have an ethical obligation to report results, and this is especially true when volunteers contribute their time as study participants in prospective experiments, whether large or small. And, to be effective stewards of precious and constrained taxpayer monies, we need to collect a minimum of standardized data.

This transparency complements existing efforts to promote data sharing, public access to NIH-funded research results, and scientifically rigorous research design, all of which ultimately benefit the research community directly, as well. By developing and sharing robust data, we maximize the value of NIH’s investment in research by allowing scientists to build upon solid results. The definition, and our clinical trial policies, are an integral part of our efforts to enhance scientific stewardship, dissemination of information, transparency, and to excel as a federal science agency that manages for results.

Why is it important to know whether you are proposing to conduct a clinical trial? Correctly identifying whether your study is a clinical trial is crucial to complying with NIH policies, many of which are now in effect, such as registering and reporting all NIH supported clinical trials in ClinicalTrials.gov and good clinical practice training. Very soon, your answer will be crucial to picking the appropriate NIH funding opportunity for your application, writing your research plan correctly (since some information will be captured in the new human subjects and clinical trials form), and ensuring that your application includes all the information required for peer review.

If you are having difficulty answering the four questions that determine whether a study meets the NIH definition of a clinical trial, we encourage you to consult the case studies and FAQs that are available on our webpage on clinical trial requirements for grants and contracts. We’ll be following up with additional blogs and NIH Extramural Nexus articles that provide more depth on the various initiatives. We strongly encourage you to look at these materials, and share them with your colleagues, to ensure that as an awardee conducting clinical trial research, you are aware of the need to register your trial and report its results.

The NHLBI implementation of increased oversight of R01-funded clinical trials through the R61/R33 mechanism restricted the timeline for a trial (planning/early enrollment in year 1, await R33 award to continue). This limits the types of trials that can be done. For example, a community trial working with a school district often needs to begin implementation of the intervention near immediately after participant enrollment, which can be conducted quickly and in large numbers – you can enroll several schools worth of children within 1 month with effective staffing. Intervention implementation may also need to occur within the first year of funding to allow for alignment with the academic year and enough time on the grant to follow students for several years. Enrollment/implementation does not happen on a rolling basis as in say, a drug trial.

I hope as other institutes implement/improve the requirements for clinical trials, they are considerate of the variety of types of trials and are flexible regarding timing for planning/enrollment/implementation.

I can’t help but quote Nancy Kanwisher here: “The massive amount of dysfunction and paperwork that will result from this decision boggles the mind.”

I’m an early career researcher doing basic human subjects research funded by the NIH. Our science is directly relevant to understanding the basic cognitive and neural mechanisms that support a healthy brain. Yet our “interventions” (a simple example: testing memory for words shown in the same font vs a different font) might now be treated with the same level of scrutiny as a true clinical trial. If so, it is difficult to even imagine the impact of this policy on our research, but a fair estimate is that every new experiment would take twice or many times as long to complete. I further suspect this will disproportionately impact early career researchers, who often have smaller labs without the resources to compensate for the added paperwork. Will grant budgets be increased accordingly? And for what? There is no clear benefit for our participants or for the general public.

It makes no sense to me (or many others) why neuroimaging studies are now being classed as clinical trials because the brain data is suddenly “health-related” outcomes. In an fMRI scan (let alone EEG), participants are doing exactly what they will do in a behavioral experiment (which is not a clinical trial), while their brain activity is observed to tell us about how (for example) the human brain processes images of faces. How is this a clinical trial?

A huge set back for cognitive neuroscience in this country.

The decision makers at the NIH who instituted this policy have to be aware that they are in effect killing basic science research with this implementation. I am specifically referring to case #18: “The study involves the recruitment of healthy volunteers who will perform working memory tasks while an fMRI is performed. It is designed to determine the brain functions involved in working memory.” This is deemed a “clinical trial.” This encompasses the entirety of basic cognitive neuroscience research. At best, this will incur serious increases in paperwork and bureaucratic demands for research that is NOT truly any sort of “clinical trial.” At its worst, it is going to nearly eliminate funding for basic science research as actual clinical trials will push out basic research in competition for monetary resources. I thought that the NIH supported basic science research, but with this move, it clearly does not. I am so incredibly disappointed by this decision. The effect that it is going to have on basic science research in the U.S. will be profound. I am incredibly saddened that after all of the hard work, effort, and dedication so many scientists have put forward to understanding how the human brain works, that we would be betrayed in this way.

I couldn’t agree more. While the goal of more oversight of trials is laudable, the implementation of all of these policies makes it nearly impossible to do and fund trials particularly for new investigators and disincentivizes collaborative trials since all sorts of hurdles have been put in place for doing even a 2-center trial (NHLBI) without going through years of planning at NHLBI without guarantee of funding for advancing to next stage. As a clinical trialist myself, I suspect the implementation of these is going to significantly discourage investigators from proposing smaller physiologic studies that provide crucial scientific and clinical data and rob the investigative community of realsitics pathways for funding clinical trials and for young investigators to get experience in clinical trials.

This broadening of the “clinical trial” definition is frankly insane. What could possibly be gained by pretending that having healthy volunteers perform a cognitive task (essentially equivalent to playing a lame computer game) for half an hour and measuring their reaction times (or even neural signals) constitutes a “clinical trial”, equivalent to trying out a new pharmaceutical on a patient population??? I have not seen a single credible argument in support of this absurd over-stretching of the “clnical trials” definition. How is having someone push buttons in response to pictures on a screen an “intervention” that affects “biomedical health outcomes”? It is as if this was cooked up by people who have absolutely no clue what we do in basic cognitive and cognitive neuroscience research. The proposed additional administrative burden and massively reduced flexibility in running research would be a huge killer of innovative basic research and a gigantic waste of taxpayer monies to pay for the additional admin costs. Our best and brightest graduate students would move from being able to follow their creative sparks to essentially becoming “research technicians” who just have to implement to the letter some experiment we proposed in a grant application several years ago. Please, someone tell me: What is the point of this???

In the scientific and clinical communities and in the general public, “intervention” is generally considered to be synonymous with “treatment.” I am a clinical psychologist and neuroscientist, but even if I were a member of the general public, I would be shocked to hear that the “intervention” my doctor planned was simply an assessment of my current functioning, even if that assessment involved asking me to do certain tasks (stick out my tongue and say “aah” for example). Many of our experimental research studies, especially in psychology and neuroscience, are the behavioral and neurobiological equivalent of asking people to stick out their tongue and say “ahh.” They are not designed to have any lasting effect on health or wellbeing. In fact, the opposite is more often true; we design the studies to have as little lasting impact as possible. If the suggestion to change the definition of an intervention has arisen because of concerns about any potential risks involved in these studies, these concerns should be addressed through the appropriate channels (i.e., in human subjects review and through institutional review boards). Please do not dilute the definition of a clinical trial by including studies without a true intervention. It will mislead the public, obstruct scientific progress, and create mountains of red tape for everyone involved, with no apparent benefit to anyone.

Neuroscientist: know that this new interpretation of what constitutes of a clinical trial deems ALL experimental (rather than observational) studies on humans funded by NIH as clinical trials (whether they use fMRI or just behavior). This is because any task/instruction to the subject will be considered an intervention, and all outcomes that NIH funds are, by definition, “health related.”

The outcomes for patients, researchers and science at large will be terrible.

– Clinicaltrials.gov will be inundated with experiments that are not testing a method for improving health, that is, they are not really clinical trials, making it harder for the public to find real clinical trials. We will have people calling basic neuroscience researchers wanting to participate in their “trials” only to find out that our studies will not improve their memory, decision making, etc. This will lead to frustration with NIH and with science as a whole (on the part of the public), and a huge waste of taxpayer money.

– Researchers will have to register basic science studies in advance with very limited ability to adjust them later based on findings of other basic science research. We will effectively be locked into wasting taxpayer dollars on research that is not good research, just because we put it in a grant proposal, possibly several years ago.

– The paperwork and reporting burden will be significant, including adding new offices/staff to manage clinical trials in universities that may not have such an office as they previously did not have a medical school or run any (real) clinical trials…

– Reviewers and study sections may employ different standards for “clinical trials” that will now be applied to basic medical science work. This means that, in neuroscience, instead of trying to understand the brain, we will be held to the standard of trying to improve it without even knowing how it works.

That is, this new regulation will potentially decimate basic neuroscience research in humans, putting us years behind where we could be in understanding the brain and really treating neural disease clinically. Worse, it will make the public think that thousands of clinical trials are leading to no clinical outcomes, suggesting to them that medical science as a whole is faltering, and should not be funded. I do hope NIH will reconsider the implications and consequences of this decision.

Case #18 is stretching the definitions NIH provides for (1) “intervention” and (2) “health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome.”

1) “Intervention” is defined as a manipulation of the subject or subject’s environment for the purpose of modifying one or more health-related biomedical or behavioral processes and/or endpoints. Examples include: drugs/small molecules/compounds; biologics; devices; procedures (e.g., surgical techniques); delivery systems (e.g., telemedicine, face-to-face interviews); strategies to change health-related behavior (e.g., diet, cognitive therapy, exercise, development of new habits); treatment strategies; prevention strategies; and, diagnostic strategies.

It is clear that all these manipulation produce a long-lasting alteration of the body or behavior. I don’t think Case #18 fits this idea. Even if memories are changed, there is no long-term change in behavior after the experiment.

2) A “health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome” is defined as the pre-specified goal(s) or condition(s) that reflect the effect of one or more interventions on human subjects’ biomedical or behavioral status or quality of life. Examples include: positive or negative changes to physiological or biological parameters (e.g., improvement of lung capacity, gene expression); positive or negative changes to psychological or neurodevelopmental parameters (e.g., mood management intervention for smokers; reading comprehension and /or information retention); positive or negative changes to disease processes; positive or negative changes to health-related behaviors; and, positive or negative changes to quality of life.

Again, Case #18 does not fit with this definition. Participating in a memory experiment does not produce any effect on participant’s biomedical/behavioral status or quality of life. It does do not produce any long-lasting effect on their body or behavior.

More generally, basic research that does not produce a long-lasting change on the body or behavior should not be classified as a clinical trial. The goal of these studies IS NOT to produce a permanent change. They are MEASURING the body or the mind, not CHANGING them.

Applying these policies to psychopathology and other basic research studies as in case 18 will put an undue burden on such studies with no benefit that I can see. I think that the definition of an intervention has to be restricted to one that is designed to reduce or prevent symptoms rather than leaving it so broad as to include any manipulation that is designed to have some measurable impact on the participants.

This onerous new requirement will indeed discourage investigators from proposing and carrying out the exact sort of creative, small-scale, physiological studies that have provided the crucial scientific background for actual clinical trials. I fail to see how this will help with the goal of making “findings … available to the public as soon as possible after the trial has concluded”. Instead, it will sterilize the very earth from which findings grow.

I am a mid-career researcher with NIH funding to study basic mechanisms of memory in human subjects. I fully agree with the other commentators that this policy will cripple the research effort. The administrative burden will be immense and it is not reasonable to assume that additional funds will be available to cover this burden. I already spend too much of my time addressing the various arbitrary administrative burdens that are required to meet NIH regulations, none of which I feel have contributed meaningfully to the quality of my research. This new NIH policy will further disrupt the work of scientists by forcing us to spend our time and mental efforts working as pencil pushers. Every new administrative burden hampers innovation and harms the scientific enterprise by reducing our ability to devote our efforts to the research we were trained to perform, rather than paperwork. This new policy is also ignorant of the dominant trends towards open science and data sharing already at play in the field that it targets. Scientists are willingly and sensibly working together as a field towards open science, transparency, and accountability in a way that makes sense and will actually lead to a better research enterprise. This NIH policy does not have the collective experience of all investigators in the field to guide it, and therefore it will be a roadblock to innovation and will not improve the scientific enterprise or the public’s ability to use science discoveries. It will reduce them.

The implication of case #18 is that almost all basic science behavioral research and experimental psychopathology research would be viewed misleadingly as a clinical trial – such research does not constitute a clinical trail in the traditional sense because there is no actual intervention and participants are not receiving a treatment. Adopting this policy will cripple research and constitute an injustice to research participants who will be consenting to participate in a clinical trial that doesn’t exist.

This is such a misguided initiative. it’s challenging to imagine what good it could do and all too easy to anticipate how likely it would be to discourage researchers from conducting the experiments that play such a crucial role in the development of our knowledge base.

I completely agree with the above comments with respect to the new interpretation of the definition to include all mechanistic studies, such as studies of basic function in healthy individuals exemplified in Case #18. This directly contradicts previous NIH guidance (updated 7/21/15) about defining a clinical trial. “Health-related outcomes are not typically temporary in nature. Temporary effects rarely have a health impact. For example, a temporary increase of blood flow in the brain observed by MRI after the administration of buspirone is not a health-related outcome because the increase in blood flow is not necessarily associated with changes in health. (Case study #13).”

Including mechanistic studies of basic brain function (whether in healthy individuals or patient groups) in clinicaltrials.gov will undermine the utility of that website, because it will swell with thousands of studies that will not be relevant to meaningful, disease-related outcomes. As other commentators mention, the burden on investigators will be considerable. I have entered studies in clinicaltrials.gov, and it is not a trivial task. Most importantly, the rigid format, designed for real clinical trials, cannot accommodate the complex data analysis for mechanistic studies. Investigators will have to spend many hours trying to shoe-horn their data into ill-specified fields. Because it will be virtually impossible to design data fields that will generalize to the huge variety of mechanistic studies, it will not be possible to use the data in meta-analyses.

I strongly urge the NIH to re-consider its expansion of the definition of clinical trials to include these mechanistic studies.

I am optimistically hopeful that when huge bodies of researchers supported for decades and millions of dollars by NIH find something problematic, NIH will listen. As highlighted by the statements ICIS and FABBS have made about the definition of clinical trials, that is where we find ourselves presently (and these are just the groups I happen to be tied to).

Further, rather than reiterate others’ points about the confusion, cost, and blanching of basic cognitive research the new rules would lead to (which others have eloquently stated), I want to point out an inconsistency in the example cases NIH provides, namely the contrast between Case 18 and Case 22.

In Case 18, a working memory task in a scanner is deemed a clinical trial because ” brain function, is a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome.” In Case 22 a behavioral task in which children do ‘learning activities’ to monitor information retrieval is deemed not a clinical trial because “this educational study is evaluating learning activities, and has no clear link to health.”

I take issue with both assessments. Measuring brain activity (as apposed to say reaction time) doesn’t make this an intervention or clinical trial, if anything, it is just like Case 22, an evaluation of ‘learning activities’, it just happens to be with healthy adults instead of children. However, I also take issue with Case 22’s classification as ‘no clear link to health’. 1000s of successfully funded grants through NIH have indeed formed the backbone of what we know about health with regard to brain activity, whether measured with behavioral outcomes or neural ones, in children and adults. Indeed, testing any ‘special’ populations or true interventions must always occur against a robust understanding of the ‘typical’ case: saying this research doesn’t concern health outcomes is an insult to the NICHD, the brain initiative, and many other NIH supported lines of research through other NIH divisions.

I hope Dr. Collins and his esteemed colleagues (who I have no doubt have both researchers’ and taxpayers’ best interests in mind!) will reconsider this change, and invite basic cognitive and developmental researchers to the table as this is discussed.

Are these changes truly a good faith effort to increase transparency? If so, this is clearly a misguided effort as the net effect will, without doubt, be punitive to basic cognitive neuroscience research. I fully support efforts to increase transparency, but there are much better options than re-labeling human neuroimaging studies with a label that, at face value, makes no sense. It is rather difficult to defend using terms that will befuddle the scientific community AND the general public. In fact, that seems quite contrary to the goals of increasing the transparency of NIH research. Moreover—and as Joel mentions—there is already a strong movement within the field to increase transparency and it would not be hard to get the field to rally behind a more sensible approach to this goal.

The apparent absurdity of this change naturally makes one wonder whether this is a more deliberate effort to push basic cognitive neuroscience research into an ill-fitting category. According to this cynical view, the intended result is that the research is, all of a sudden, less in-line with the NIH’s mission (gee, this neuroimaging study doesn’t sound like a good clinical trial) and, therefore, basic science research is less likely to be funded. If this is, in fact, an effort to squeeze out basic cognitive neuroscience research from NIH’s portfolio, it is not only sad, but—as many (actual) clinical researchers would agree—it is also incredibly short-sighted with respect to the NIH’s long-term goals.

Like many others in the field of cognitive neuroscience, my head is spinning trying to make sense of this.

Why were brain and behavioral scientists blindsided by the implications of the revised NIH definition of “clinical trial” (NOT-OD-15-015)? As Mike pointed out: “The definition was published in 2014, after extensive public input, and affirmed, after even more public input, in our policy published in September 2016.”

In the NIH grant application process, we have been accustomed to the black-and-white Yes/No “Clinical Trial?” question (Human Subjects Section, PHS 398 Cover Page Supplement). For basic research studies, the common sense answer–without question–is No. However, the 2014 Notice begins with a fair warning: “The purpose of this Notice is to inform the research community that NIH has revised its definition of ‘clinical trial.'” Therefore, we had better read on to see if the revised definition could change No to Yes.

The next sentence reads: “The revision is designed to make the distinction between clinical trials and clinical research studies clearer and to enhance the precision of the information NIH collects, tracks, and reports on clinical trials.” Very good so far: There are important distinctions between clinical trials, clinical research studies, and basic research studies (implied). At one end of the research spectrum, we understand that basic research encompasses exploratory and confirmatory studies to identify robust phenomena and to explain their mechanisms. At the other end of the spectrum, clinical trials are designed to test something that (if successful) could directly impact FDA-regulated clinical practices. The fundamentally important distinction between basic research studies and clinical trials isn’t addressed in the notice. It’s taken for granted. Implicitly, we are led to expect that basic research to understand how the brain works when it’s not broken (with the help of consenting participants) would remain unaffected by the revision. Explicitly, we are informed that the revised definition should “make the distinction between clinical trials and clinical research studies clearer”: It should not introduce confusion where there had been no confusion before.

Nevertheless, clinical research studies span a large segment of the spectrum between basic research studies and clinical trials. Basic researchers who seek NIH funding motivate their studies of typical individuals by considering potential clinical relevance. Importantly, to understand how the brain works “when not broken” (basic research) and “when broken” (clinical research) are mutually illuminating objectives. In particular, the NIMH Research Domain Criteria Initiative (RDoC) encourages studies that span the full range of normal variation and that cut across disorders. Consequently, because all NIH-funded studies have potential clinical relevance, and also because RDoC encourages the integration of basic and clinical research studies, we had better keep reading.

The next sentence assures us: “It is not intended to expand the scope of the category of clinical trials.” Now we have confirmation that the revised definition only clarifies borderline cases. As a corollary, we fully expect that it is not a radical revision which would reclassify a whole category of previously funded studies, such as basic cognitive neuroscience research.

At this point, when we read the revised definition itself, nothing pops out that obviously should have caused alarm in October 2014. As others noted, what became alarming is the aberrant interpretation of the revised definition that leads to the anomalous reclassification of Case #18 as a “clinical trial”. The interpretation is aberrant because it contradicts the stated intention not to expand the scope of the category of clinical trials.

These considerations may help to explain why many of us did not participate in the earlier formal discussions regarding the revised NIH definition of “clinical trial”.

If I may add a brief summary, two apparent contradictions between the published purpose of the revised definition (NOT-OD-15-015) and its interpreted consequences (Case #18) are: (1) the consequence of blurring the distinction between clinical trials and basic research studies (traditionally bridged by clinical research studies) seems to contradict the intent to make the distinction between clinical trials and clinical research studies clearer; and (2) the consequence of reclassifying an important category of research (i.e., basic and clinical cognitive neuroscience studies) as clinical trials seems to contradict the intent not to expand the scope of the category of clinical trials.

As an investigator who studies cognitive development, I worry about Case 22. On the one hand, it’s nice to be exempted from regulatory burden. On the other hand, if research is considered not clinically relevant, will there later be criticism of funding from NIH? In addition, a colleague has already been confused in submitting a grant for retrospective analysis of data from a longitudinal study, in which children did participate in cognitive and social tasks. She was told that her research WOULD be considered a clinical trial. No good end is served by a definition that flies in the face of everyone’s common-sense understanding of the term.

I agree with the comments posted above. Though I fully share the objectives of improving data sharing and promoting rigor in design, this particular policy misses the mark by sweeping up basic human cognitive and neuroscience research and trying to shoehorn them into regulations and requirements designed for clinical trials. As others have already noted here and elsewhere, this onerous administrative burden is likely to dramatically slow the pace of scientific progress and will have a disproportionate negative impact on basic researchers, early career researchers, smaller research institutions, grant review, collaborative research, and true clinical trials in the public interest. Further, as this expanded definition targets basic experimental research only in humans, it seems likely that progress in basic human neuroscience will be selectively chilled, and the NIH portfolio in basic science may shift accordingly. Were this to happen, it would be damaging for brain science in general. As has been argued repeatedly from evidence, contributions from both human and animal basic neuroscience are essential if one’s goal is to promote brain health (for example, see Badre, Frank, and Moore, Neuron, 2015). If the only goal of this policy is to promote data sharing and rigor, these goals apply equally to research conducted in all species and to non-experimental work, as well. Thus, to single out basic human experimental research for this heavy administrative burden appears arbitrary and poses asymmetric costs for conducting only one kind of research. The long-term negative impact of such a policy on all basic neuroscience at the NIH and in the US in general is hard to overstate. I strongly urge the NIH to reconsider this definition and to seek policies that more effectively promote strong and open science across the board, including by leveraging efforts already on-going in the field.

I agree with the general spirit of the comments posted here. We have been arguing for some months that, while the quality and transparency goals of this policy are good, the clinical trials approach does not seem to be the best solution. See, for example, the Science news article, “Some scientists hate NIH’s new definition of a clinical trial. Here’s why”

However, if we are going down this path, let’s look at the case studies that are intended to clarify the definition of a clinical trial. I appreciate the effort but the outcome is not clear to me. Let’s focus on Case #18 (mentioned extensively in prior comments) along with #22 and #24:

In #18, a study of working memory is a clinical trial because: “the effect being evaluated, brain function, is a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome.”

What does “brain function” mean here? Is it brain function because you are in an fMRI scanner? Are reaction times or eye movements not “brain functions”? If not, what are they?

So, now we jump down to #22

“The study involves the recruitment of healthy children who will be presented with a series of learning activities. It is designed to evaluate the children’s ability to retain and retrieve specific information.” How is that different from retaining and retrieving specific information in the working memory study of Case 18? It would appear that the critical difference really is the magnet. This is a sort of oddly dualist position where fMRI studies the “brain” and presenting children with memory tasks studies something else that is not the brain. Alternatively, we need to imagine that some fundamental difference between the memory tasks in #18 and #22 is envisioned but I can’t figure out what that would be.

Turning to Case #24; it is not a clinical trial because “…, the study is designed to learn about participants’ opinions on the readability of the different printed announcements. It is not designed to evaluate the effect of the printed material on the participants.” So it is not an intervention. What, then, is the intervention in #18? There is no obvious intervention in the sense of changing anything more than momentarily by, one presumes, changing the memory load. Case #24 seems to have two or more different conditions, applied to the same observers. Indeed, #24 seems much more likely to lead to an actual intervention, down the line, when the results are used to change the font on the library’s announcements.

We could go on. Others could look at other ambiguities raised by other cases. I am not trying to be obstructionist here, but the case studies do not clarify adequately. Virtually all human behavioral science involves manipulating a dependent variable and measuring responses that most of us would regard as the product of the human brain. It is possible that the goal of the new policy is to declare all such work to be a “clinical trial”. That is unfortunate for reasons articulated in other comments above and elsewhere. If that is not the goal, then I think we in the behavioral and brain science community will need more and different guidance. The case studies are a valiant effort but I don’t think they are clear enough to guide the field.

Sincerely

Jeremy Wolfe

President – Federation of Associations of Behavioral and Brain Sciences

My concern is that the combination of the new definition of clinical trial and the revisions to the common rule make it very difficult for behavioral researchers to determine whether research of theirs that has not been previously classified as a clinical trial will be classified as one going forward. Depending on what one reads, it appears either that almost all nonclinical behavioral research will be treated as clinical trials going forward (because they record behavioral responses), or that the new regulations are being interpreted somewhat more narrowly (and with more of a conventionally clinical focus). NIH’s new guidance on these changes is currently quite confusing, although I appreciate that making these determinations is very difficult given the breadth of the research supported by NIH.

Reading the definition of clinical trial that NIH provides (in NOT-OD-15-015), a behavioral researcher such as myself might think that all of their research going forward would be treated as a clinical trial, when there is nothing particularly clinical about it. NIH makes a point of excluding some behavioral research from this definition from the outset (namely surveys, questionnaires, user preferences, and studies involving focus groups, or assessments of teaching methods), but this leaves a great deal of research that might now be classified as clinical trials.

However, NIH also provides a tool for researchers applying for funding to use to determine whether their research meets this new definition (https://grants.nih.gov/ct-decision/index.htm), and reading through it, it has a much more conventionally clinical focus than the definition. The idea of assigning subjects to an intervention is defined quite clinically, the idea of interventions themselves are similarly very clinically-focused (e.g., the health and well-being of the subjects, rather than the broad umbrella suggested by the definition), and the outcomes are also defined relative to subject health, rather than general physiology or behavior in a broad sense. This tool suggests that much of the existing behavioral research that I am concerned about would not fall under the the new definition of clinical trials, because said behavioral research does not have a direct focus on health or health-related outcomes; it is focused on better understanding the brain.

Related to this, the new definition of clinical trial the NIH is using is part of the major revisions to 45 CFR part 46, the Common Rule. This major change to human subjects protections includes significant changes to what kinds of research will require IRB oversight going forward, and may address many of the concerns I and my fellow researchers have about these impending changes. In particular, the expansion of the exempt research case (45 CFR part 46.104; “Exempt Research”) suggests that much noninvasive behavioral research will not longer require IRB review, due to minimal physical and emotional risk to participants. It is unclear how NIH’s guidelines intersect with this change in the Common Rule, and one interpretation could be that much of the behavioral research that could be seen as under the clinical trial definition is, in fact, exempt from review entirely under these revisions, since it would fulfill the requirements for “benign behavioral interventions” described in 45 CFR part 46.104(3)(i).

At the moment, it is unclear whether a non-invasive experiment (for example, showing subjects a visual stimuli and having them make an eye movement toward it, or showing them a video and asking what they perceived as happening in the video, or having a subject in an fMRI watch a video and recording neural activation to moving stimuli versus static stimuli) would be a clinical trial or not. The NIH’s core definition (NOT-OD-15-015) suggests that all of these would be. NIH’s decision tool suggests that none of them would be, and the revisions to the Common Rule might render the first two, if not all three, exempt from IRB review due to the minimal risk to participants. Given the penalties for getting this determination wrong, I would like to know how best to classify this kind of behavioral research going forward when applying for NIH support.

I strongly agree with the general sentiment expressed above; namely that while the goals of increasing transparency are laudable, the clinical trials mechanism is precisely the wrong way to achieve them.

My lab runs both basic cognitive neuroscience studies as well as registered clinical trials, and the difference in administration burden is enormous. I’m not sure the extent to which NIH is aware that many institutions impose substantial internal requirements beyond what NIH requires for any study meeting the definition of a clinical trial (regardless of whether it is funded by NIH). These include lengthy review processes by offices of clinical research, which typically take 2-3 months per study. I really hope the NIH will consider the impact of this proposed increase in regulation and reporting; it will be absolutely crippling to the cognitive neurosciences and will ultimately slow the discovery of life-transforming treatments.

It is also completely unnecessary to achieve the stated aims. Data sharing repositories have already been put in place by NIMH for all funded studies (e.g., the RDoC database). There’s no reason the clinical trial designation is needed to improve transparency and open access of science.

It seems relevant to note that this move goes in the complete opposite direction of the changes to the common rule approved just last year, which aimed to reduce the burden on researchers for regulation of minimal risk studies, many of which are exactly the type of studies that would now be clinical trials. Does it even make sense to propose a regulatory system wherein a study could potentially be designated both “IRB exempt” and a “clinical trial”?

I sincerely hope NIH will reconsider this policy, and finds alternative strategies for achieving its goals of increasing reporting transparency. The designation of “clinical trials” was never intended for these purposes.

FABBS President Wolfe makes a strong case suggesting that these guidelines are not ready for prime time. To repeat, “Virtually all human behavioral science involves manipulating a dependent variable and measuring responses that most of us would regard as the product of the human brain.” If ever science needed clarity, this is a good instance. The confusion and paperwork that will be required if this NIH definition of a clinical trial takes effect would divert energies from important scientific research.

I am an early career researcher in cognitive development, and having recently sought funding from NICHD, have found the definition of a clinical trial to be confusing and inconsistent across sources. The scenario in Case Study #22 is most similar to my research. However, Case Study #22 directly contradicts the definition of a clinical trial provided in NOT-OD-15-015. NOT-OD-15-015 defines health-related biomedical or behavioral outcomes as including “positive or negative changes to psychological or neurodevelopmental parameters (e.g., mood management intervention for smokers; reading comprehension and /or information retention).” So, “information retention” is a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome, but in Case Study #22, a study that is “designed to evaluate the children’s ability to retain and retrieve specific information” fails the four-question test because its outcome – information retention – has “no clear link to health.”

If we believe NOT-OD-15-015, the new definition applies to all basic experimental research that studies “information retention”, whether in children or adults (i.e., cognitive psychology, cognitive development). However, Case Study #22 directly contradicts this, so whether the new definition of clinical trial applies to these areas of research is unclear.

Further, if the conclusion is that studying children’s learning is not a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome, this makes me wonder why NIH would fund research that is not considered health-related. This kind of research is explicitly part of the mission of the NICHD Child Development and Behavior Branch.

A major concern I haven’t seen raised yet is that Institutional Training (T) Awards will not be allowed to support clinical trials. This would cut off neuroscience from these training grants – and potentially cut off all of basic cognitive and developmental psychology research, depending on the answers to the questions posed above.

This initiative raises serious concern for me as a researcher of neuroscience. While I fully support the general goal of making publicly funded (clinical) studies more transparent to the public, I seriously doubt whether the approach taken to overly broaden the definition in this initiative is aligned with the interest of taxpayer.

Many human behavior and brain imaging studies are aimed to elucidate basic mechanism of how brain functions and how we are able to achieve many daily tasks. The knowledge yielded in such studies often address curious questions of many, such as how we store the information we just read from a textbook into our long term memory, how our emotion influences our choice between benefit in the short term and welfare in the long term. Very often, studies might involve non-invasively and indirectly measuring the activity in the brain while participants are performing a simple task, using techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). While such studies are both basic and possibly interesting to many people outside the scientific community, they are not necessarily as closely related to health as topics such as diabetes, cancer, or drug addiction. The outcome of such studies might distinguish different hypothesis of a specific aspect of brain functions, but in very rare cases can their results influence how a doctor should recommend a therapy to a patient or how a person should change its health-related behavior. Classifying such studies means that conducting such a experiment addressing such a basic science question would require the researcher to spend enormous amount of time on registering the study, obtaining excessive steps of approval and delaying the delivery of the scientific findings. Research institutes would have to spend extra amount of human resources and money to perform extra evaluation to proposals of such studies, along side those clinical trials that are waiting to be evaluated and approved. I anticipate either increase amount of spending of taxpayer money on unnecessary inter-institute paperwork and evaluation or delay of the conduction of urgent clinical studies because of the dilution of focus of the personnels in institutional review boards, or both.

This should not be mistaken as saying the basic science studies involving human behavior or neural imaging conducted everyday in universities are not evaluated or approved seriously. Careful examination by institutional research boards are indeed required prior to performing such studies, with the protection of participants’ safety put into one of the major concerns. But they do not need unnecessary amount of extra examinations or approvals because their outcomes are not as closely related to the health of general public as the real clinical studies.

In either case, the unnecessary cost brought about due to this broadening of definition of clinical trials is passed on to the tax-payers.

My opinion is, the amount of caution placed on performing a study should be proportional to the potential impact it has on any health-related issues.

Unfortunately, the current definition and the case studies (such as #18 in https://grants.nih.gov/policy/clinical-trials/case-studies.htm) consider these studies as clinical trials. While at the same time, a study focused on learning activities but does not involve brain imaging is not considered as health-related (#22 in the link above). As Jeremy pointed out, the only clear distinction between these two examples is whether a brain imaging is performed. It really makes no sense to claim that learning activity in the later case does not involve the role of the brain of a participant. Then why is it not “brain function”? Is learning by a human not a function of his/her brain? I am not arguing that both of these examples should be considered clinical trials. On the contrary, simply classifying whether a study is health related based on whether it measures some physiologically related quantity is not a justified rule with scientific basis.

My concern is that the combination of the new definition of clinical trial and the revisions to the common rule make it very difficult for behavioral researchers to determine whether research of theirs that has not been previously classified as a clinical trial will be classified as one going forward. Depending on what one reads, it appears either that almost all nonclinical behavioral research will be treated as clinical trials going forward (because they record behavioral responses), or that the new regulations are being interpreted somewhat more narrowly (and with more of a conventionally clinical focus). NIH’s new guidance on these changes is currently quite confusing, although I appreciate that making these determinations is very difficult given the breadth of the research supported by NIH.

Reading the definition of clinical trial that NIH provides (in NOT-OD-15-015), a behavioral researcher such as myself might think that all of their research going forward would be treated as a clinical trial, when there is nothing particularly clinical about it. NIH makes a point of excluding some behavioral research from this definition from the outset (namely surveys, questionnaires, user preferences, and studies involving focus groups, or assessments of teaching methods), but this leaves a great deal of research that might now be classified as clinical trials.

However, NIH also provides a tool for researchers applying for funding to use to determine whether their research meets this new definition, and reading through it, it has a much more conventionally clinical focus than the definition. The idea of assigning subjects to an intervention is defined quite clinically, the idea of interventions themselves are similarly very clinically-focused (e.g., the health and well-being of the subjects, rather than the broad umbrella suggested by the definition), and the outcomes are also defined relative to subject health, rather than general physiology or behavior in a broad sense. This tool suggests that much of the existing behavioral research that I am concerned about would not fall under the the new definition of clinical trials, because said behavioral research does not have a direct focus on health or health-related outcomes; it is focused on better understanding the brain.

Related to this, the new definition of clinical trial the NIH is using is part of the major revisions to 45 CFR part 46, the Common Rule. This major change to human subjects protections includes significant changes to what kinds of research will require IRB oversight going forward, and may address many of the concerns I and my fellow researchers have about these impending changes. In particular, the expansion of the exempt research case (45 CFR part 46.104; “Exempt Research”) suggests that much noninvasive behavioral research will not longer require IRB review, due to minimal physical and emotional risk to participants. It is unclear how NIH’s guidelines intersect with this change in the Common Rule, and one interpretation could be that much of the behavioral research that could be seen as under the clinical trial definition is, in fact, exempt from review entirely under these revisions, since it would fulfill the requirements for “benign behavioral interventions” described in 45 CFR part 46.104(3)(i).

At the moment, it is unclear whether a non-invasive experiment (for example, showing subjects a visual stimuli and having them make an eye movement toward it, or showing them a video and asking what they perceived as happening in the video, or having a subject in an fMRI watch a video and recording neural activation to moving stimuli versus static stimuli) would be a clinical trial or not. The NIH’s core definition (NOT-OD-15-015) suggests that all of these would be. NIH’s decision tool suggests that none of them would be, and the revisions to the Common Rule might render the first two, if not all three, exempt from IRB review due to the minimal risk to participants. Given the penalties for getting this determination wrong, I would like to know how best to classify this kind of behavioral research going forward when applying for NIH support.

I wanted to add my support to the comments above. To clarify, the problem here is not the new definition of clinical trials, which is clear and reasonable, and specifically stated that it “is not intended to expand the scope of the category of clinical trials” (NOT-OD-15-015).

The very alarming issue is the application of this definition in the case studies, specifically case study #18. Basic neuroscience research is not designed to “modify” a subject’s “biomedical or behavioral status or quality of life,” but simply to measure how a subject’s brain is currently functioning. Categorizing this type of research as a “clinical trial” violates both the NIH’s stated desire not to expand the scope of clinical trials and the common-sense understanding of what a clinical trial is.

For early-career researchers such as myself who have (or are starting) tiny labs, and no staff to handle this increased regulatory burden, this would be a massive setback in our ability to run imaging experiments, and has no benefits for any of the parties involved – investigators will be able to run fewer experiments and fund fewer trainees, NIH awards will yield fewer results, and patients looking for clinical trials will be upset and confused.

There is a clear consensus that this interpretation of the new definition is a mistake, and we urge you to response to our concerns before this policy is implemented.

Some further clarification:

I appreciate the time and thought that has gone into this new definition of clinical trials, and I fully support the desire to ensure transparency and dissemination of clinical trial data. Researchers in basic human neuroscience do not take issue with the way clinical trials are now being defined, and we are not arguing against applying these policies to “early exploratory trials, small trials, trials assessing only safety, or trials that terminate before reaching enrollment targets.”

But we were shocked by the inclusion of a basic working memory neuroimaging experiment (case study #18) as a clinical trial, since we believe that this experiment *does not fit* the NIH clinical trial definition. We do not understand how any reasonable reading of the “intervention” definition (“manipulation of the subject or subject’s environment for the purpose of modifying one or more health-related biomedical or behavioral processes and/or endpoints”) could encompass “working memory tasks” intended to characterize (but not modify) an ongoing brain process.

Again, our intent is to not to change the clinical trial definition, but to question why this definition is being interpreted in this way, and to make it clear that this interpretation is going to cause substantial harm to our research community without any clear benefits for any of the stakeholders.

As a non clinical researcher, I am seriously alarmed and concerned by the broad inclusion of what amount to basic research under the “clinical trial” umbrella. Here is what one of my young clinical colleague just expressed to me: “If this new NIH definition goes into effect, it will substantially hurt the productivity of our labs. My staff and I estimate that if all ongoing studies were suddenly designated as clinical trials we would need to hire 2-3 additional full-time research assistants to maintain our current rates of recruitment. Moreover, it would curtail our educational mission, as it would significantly impede our ability to offer our undergraduates hands-on research experience.” As citizen of a R1 institution, those are serious reasons to worry.

I would like to echo and underline the concerns of my colleagues in regards to the designation of basic neuroscience studies as clinical trials (Case #18). Upon reading the documentation for the new definition of a clinical trial, I thought it was quite clear and sensible. And as I read the case scenarios, I could understand the designations, until I got to case #18. This appears to be an error in designation. Changes in brain function associated with the completion of memory tasks are not purposeful changes designed to improve that particular participant’s health outcomes. In fact, as several others have noted, the brain functioning changes that are observed in such studies are short term in nature, and the memory tasks are nothing more than stimuli designed to invoke physiological responses that may differ across participants (perhaps depending upon some third variable of interest). Might the designation of Case #18 as a clinical trial be an error that could be corrected?

Assuming the solution is not as simple as that, I would urge the NIH to reconsider the new clinical trial designations as set forth here, such that they better reflect the stated goals of increased clarity, increased scientific innovation, and the promotion of more rigorous intervention studies designed to meaningfully improve health outcomes. Let’s not drive talented neuroscientists out of academia by adding undue burden to their research programs–that would be counterproductive to our shared long term goals.

“Case 18”, which mischaracterizes all human task fMRI studies as clinical trials, does not follow logically from the 2014 definition of a clinical trial.

To see that this is so, consider what would happen if we were to apply the reasoning behind Case 18 (see below) to a hypothetical human research study in which participant screening includes visual acuity assessment using an eye chart:

• Yes, participants are prospectively assigned to an intervention – a visual letter-naming task.

• Yes, the study is designed to measure the effect of visual letter-naming tasks on speech.

• Yes, the effect being evaluated, speech, is a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome.

This study is a clinical trial.

Thus, Case 18’s curious logic compels the conclusion that any human research study in which participants’ visual acuity is assessed with an eye chart is a clinical trial. This is plainly inconsistent with a reasonable person’s understanding of the 2014 definition of a clinical trial.

Specifically:

• Task fMRI is a measurement, not an “intervention”.

• Like other measurements, task fMRI is intended to yield data, not to have an “effect on a health-related or biomedical outcome”.

By asserting that all such measurements are interventions and that the resulting data are health effects, thereby erroneously characterizing all task-fMRI human research studies as clinical trials, NIH will harm science and public health in these ways:

• NIH will quell innovation;

• NIH will chase talented people out of this important field;

• NIH will drown valuable information regarding true clinical trials available at clinicaltrials.gov in a torrent of irrelevant reports from newly-defined (“fake”) clinical trials, hindering patient access to medical treatment.

If NIH reclassifies all task-fMRI human research studies as clinical trials, and if acquisition and analysis protocols for these newly-defined clinical trials are to be as rigidly constrained as those for true clinical trials, thereby reducing flexibility in investigating human brain function, then the best work in this field will, more and more, be performed outside of the USA.

In summary, the NIH policy (effective January 2018) that mischaracterizes all task fMRI studies as clinical trials, per Case 18, is harmful to science and public health. It should be withdrawn and not implemented.

P.S. From :

Case #18:

The study involves the recruitment of healthy volunteers who will perform working memory tasks while an fMRI is performed. It is designed to determine the brain functions involved in working memory.

• Does the study involve human participants? – Yes, the healthy volunteers are human participants.

• Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? – Yes, the participants are prospectively assigned to an intervention, working memory tasks.

• Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? – Yes, the study is designed to measure the effect of working memory tasks on brain function.

• Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? – Yes, the effect being evaluated, brain function, is a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome.

This study is a clinical trial.

P.P.S. My suggested correction to Case #18:

Case #18 – CORRECTED:

The study involves the recruitment of healthy volunteers who will perform working memory tasks while an fMRI is performed. It is designed to determine the brain functions involved in working memory.

• Does the study involve human participants? – Yes, the healthy volunteers are human participants.

• Are the participants prospectively assigned to an intervention? – No, the purpose of the test is not to modify an outcome – it’s to measure working memory and the brain functions associated with it.

• Is the study designed to evaluate the effect of the intervention on the participants? – No, the study is designed to measure baseline working memory and related brain functions.

• Is the effect being evaluated a health-related biomedical or behavioral outcome? – No, there is no intervention effect being measured – rather it’s the subject’s existing capacity for working memory.

This study is not a clinical trial.

I agree that the expansion of the definition of a clinical trial will be a significant impediment to research. It would increase the demands on personnel time at multiple levels in research universities. As mentioned by several respondents, investigators will be required to commit additional time to the completion of extensive paperwork to propose and initiate the study. More effort will also be required for research personnel to complete additional training and certification, as well as everyday paperwork in the execution of the research. At the administrative level, there would be a dramatic increase in the demands on university research offices that will create the need for greater staffing. This is especially problematic in light of recent proposals for decreases in support for university research infrastructure through reductions in federal F&A levels.

The expanded definition of clinical trials also has the potential to confuse the general public. Most assume that a “clinical trial” involves the administration of a treatment or intervention aimed at altering symptoms. Designating a study that involves no effort to alter symptoms as a “clinical trial” will be misleading.

I generally agree with the points of my colleagues above. To avoid being redundant, I will focus on two issues that have received less attention above: (1) The Catch 22 of defining your research as health-related, and (2) Inconsistency with NIH policy encouraging a lower median/average age of PIs for R01 grants and other similarly-sized grants.

(1) Catch 22 of defining your research as health-related. One potential answer I could imagine from NIH is to frame your research in a manner that would not qualify as a clinical trial. Others have pointed out the ambiguity in the case studies such that the same research project could be classified as a clinical trial or not depending on whether it is framed as being health-related. If you choose the health-related framing, your work is classified as a clinical trial and subject to a whole host of strict regulations that slow research substantially. If you choose a framing that is not health-related, it seems your grant proposal would be considered out of scope of NIH. Why would the National Institute of Health fund a non-health related project?

(2) Recently, NIH has advertised a desire to lower the median/average age of a PI for R01 grants and other similarly-sized grants. The new clinical trial definition is likely to increase the age of PIs. To get IRB approval for clinical trial research, PIs rely heavily on employees that help gather information and prepare paperwork. Younger PIs are less likely to have employees available for helping with paperwork (these are typically paid by R01-like grants). Older PIs are more likely to have staff that can help with the paperwork. Thus, young researchers will be differentially impacted by the changes. The changes will increase the structural imbalance that NIH has identified and expressed the desire to fix.

From a personal perspective, I recently received my first grant as PI from NIH to investigate questions related to Alzheimer’s disease (a R21). I had been planning on submitting a R01 following up on the R21. However, if the new clinical trial definition goes into effect, I am likely to drop this line of work and instead focus on ones that would be funded by the DoD, which do not have the same onerous requirements.

More broadly, I have not heard a single researcher outside of NIH that supports these new guidelines. If there were a well-advertised public review period that we should have spoken up during, I would suspect there are researchers supportive the new guidelines. If so, where are they?

One reason many of us in the human subjects research community have been blindsided is that we were preparing for the new Common Rule that is in limbo. It would have made the approval process easier for minimally invasive interventions. I am aware that different agencies have different goals, but it had seemed like a joint effort across the different government agencies that fund human subjects research.

I appreciate the effort at NIH to increase transparency of research and aid health-related research. However, the proposed changes will increase regulations in a manner viewed as unnecessary and burdensome by the general scientific community.

Sincerely,

Joseph L. Austerweil

Assistant Professor of Psychology and Computer Science (affiliate)

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Disclaimer: The above comments are my own and have not been assessed or endorsed by the University of Wisconsin. They should not be taken as the opinion of the University or any other group affiliated with it.

What a distressing series of developments. I think I understand, and agree with, what they are attempting to accomplish here. But the sweeping nature of the new rules will make undertaking any even basic science research to be far more onerous, and likely result in many issues of ‘non-compliance’ and similar due to poor definitions. How can a working memory fMRI study be considered an intervention to measure brain function? We aren’t altering anything about the person per se, simply asking them to do a simple task to evoke the needed physiological state for a measurement. It is a far cry from a clinical trial or related intervention, and adding on to such studies the rather bulky requirements of clinical rials will impeed a lot of research, and add substantial cost to that research which is conducted.

I think these rules clearly need reconsideration and revision to allow for the conduct of basic research wtihout the burdens of a clinical trials designation.

We thank you for your feedback here in the blog comments. NIH developed the case studies as a “living document” to provide guidance for investigators about whether their research meets NIH’s definition of a clinical trial and therefore is covered by our policy to assure dissemination and transparency. We anticipate updating the case studies document, including Case 18, within the next two weeks and as needed on an ongoing basis.

Just two points for now:

1. The greatest damage that will be wrought if NIH digs in on this misguided policy is not in my view the bureaucratic burden, annoying as that would be, but the devastating impact on discovery science. This new policy will kill exploratory research, which is the lifeblood of discovery. The most important discoveries I have made in my scientific career have come from just messing around trying things on a few subjects on a whim. It would be impossible, and senseless, to register these explorations, which do not even count as pilot research. Sometimes the hypotheses are not even clear. Yet this is where discoveries come from. We discovered the PPA when we decided just to see what happened in the brain when people looked at scenes. We had no idea what to expect, we just thought we would give it a shot, and BOOM there was the PPA. This study would not have been possible with NIH’s new policies. What, I would say we’re just gonna scan a few subjects looking at scenes for the hell of it? And that would be a clinical trial that I would register? Please come to your senses, NIH!

2. The idea that the definition of a clinical trial has been around since 2014 and has already been vetted is wrong: Most of the basic researchers impacted by NIH’s policy would just never think to even read the definition, because it would not occur to any sane person doing basic research on the human mind and brain that NIH would consider their studies clinical trials. So NIH should stop replying to comments by saying this is an old definition that has already been vetted. It most certainly was NOT vetted by the people it impacts.

Nancy Kanwisher

As a cognitive neuroscientist in academia (and a former NIH program officer), I heartily concur with the grave concerns noted above by my colleagues on both conceptual and to be sure, on practical grounds. In fact, while at NIH, to the extent that I could, I tried to ensure that even single-dose “challenge” studies of an acute medication effect on brain fMRI response, or an acute behavioral response, were not ensnared in the regulatory burden of a clinical trial classification. My interpretation, then and now, is that central to the essence of a clinical trial is a “sustained” change (or no sustained change) in health-related STATE of the participant.

In addition to a clear reversion back to previous guidance that specifies a sustained change in health state, I think a compromise could be reached that would improve transparency (that NIH wants) while minimizing the added burden of transparency. Add a required electronic component to the final progress report of any award that simply has a few fillable fields like “Intervention or experimental manipulation” followed by “Dependent variable or outcome measure” followed by “Observed effect of the intervention or manipulation on participant outcomes or dependent variable.” 500 character limit for each field. This information could get appended to the public record of the grant in NIH RePORTER, under a tab called “Findings.” Make NIH support of any investigator contingent on previously-linked funded support as Key Personnel contingent on these fields having been entered by that PI or the PI of a completed grant on which the applicant was co-I. Done. The public can see what became of those funds, and it would take all of 15 minutes for the investigator. You can do this, NIH.

Better yet, in the spirit of open science with a priori hypothesis registration, require the fields of intervention and dependent variables, with an additional field “Expected or hypothesized results” to be entered and tagged to RePORTER *before* release of initial funds. Then make future funding contingent on the results field being added as part of the final progress report process (and put more teeth into final progress report compliance).

It will cause much more harm than good to create vast confusion about what counts as a clinical trial. Both cognitive neuroscientists and the public have a clear understanding that much research done with fMRI is basic discovery research — designed to investigate the basic mechanisms of cognitive function in the brain, not to test the efficacy of a potential treatment. We recruit and debrief participants with this clear message: that their contributions help us to discover how the brain works, which might (among other things) lead to future interventions. The NIH’s commitment to funding and supporting discovery science, as the engine of future medicine, is undermined and confused by this new definition which simply pretends that distinction does not exist.

I strongly support encouraging data sharing, code sharing, and pre-registration through a voluntary and flexible system (like the Open Science Framework and OpenfMRI), as long as we do it within the framework of basic discovery research.

The current proposal will increase burdens on basic science, and decrease funding opportunities. These sweeping changes were made without participation of the scientists affected. The public call was for feedback on a definition of “clinical trials”. Scientists like me, who do discovery research, didn’t respond, precise BECAUSE we do not do “clinical trials” research.

I’m just going to add my voice to the chorus here to note that the evolved definitions of “intervention” and “health related” have swept up a vast amount of work that bears no semblance to a true clinical trial. If the goal is enhanced rigor, we have options like pre-registration to use, but the solution here does not help the overall science and will curtail a large amount of studies.

Like others, I see Case 18 and 22 are key. In addition, the FAQ entry stating that, by definition, anything NIH funds is “health related” adds into the mix. That both are “interventions” is a serious expansion of the term as it now means any time we have a control condition (doing task X vs. Y), it’s an intervention. In prior definitions, this was restricted in scope by “health related” which meant that it had to have some feasible, long-term health effect. Now that any brain measure is health related, we’re up a creek.

One thing though that I haven’t seen in the tread (apologies if I missed it) is an implication of the contradictory notion that an MRI scan must be health-related while behavioral tests only are not. Look at #3 vs. #4 in the FAQ:

https://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/faq_clinical_trial_definition.htm#5221

Behavior needn’t be health related but all NIH studies are, by definition, health related.

That’s only part of my concern. The larger part is when it comes to neuropsychological testing. The goal of this is to get a readout of some notion of cognitive and brain health. Why do we do the MMSE if not to get a quick readout on brain status? That seems much more health related than a simple structural in a healthy 20 year old. Their logic would dictate then that any time we do a neuropsych test, we’re into “health related” (again, above it says that anything NIH funded is health-realted anyway), opening this into a clinical trial. Now much of what the field of “cognitive neuroscience” does is map between behavioral tasks and some neural measure, so if something like a memory task of mine is an index of brain function, it’s health-related. There goes the levee – the entire field – even a quick pilot test on the computer in some undergrads – must be registered as a clinical trial.

Craig

From the perspective of a clinician scientist who works in the UK and is not funded by NIH, this is worrying. The first conclusion that most outsiders would come to is that this is simply a means of artificially inflating numbers of studies classified as clinical trials, when they clearly are NOT clinical trials.

This has huge potential for reputation loss for NIH as well as damaging impact on basic neuroscience. Please think carefully about the consequences.

Two points – a general one, and a matter specific to the fMRI case, case 18.

The general issue is that I am very concerned about the undue confusion that the new interpretation of “clinical trial” would generate among members of the public: under the new interpretation, individuals with a medical condition seeking clinical trials relevant to their diagnosis and treatment would have to wade through a database that has been diluted with irrelevant entries, and/or would likely waste a substantial amount of time seeking enrollment in studies that are in fact non-clinical.

The second point is a propos the fMRI case (#18): I believe that the definition of clinical trial, when properly applied, indicates that this case is not a clinical trial. The annotation to the definition states, “’intervention’ is defined as a manipulation of the subject or subject’s environment for the purpose of modifying one or more health-related biomedical or behavioral processes and/or endpoints.” However, as stated in case 18, the purpose of the study is to determine brain functions involved in working memory, not to modify them. Even if working memory is considered a health-related process or endpoint, the purpose of the study is to assess these functions, not to modify them. So case 18 should not be considered a clinical trial.

I wholeheartedly agree with FABBS: “We agree with the goal of transparency in research, but disagree that sweeping basic science research into a clinical trials framework is the way to accomplish it. Simply put, we would like find a away to support the

goals without becoming mired in a clinical trials regime that is not suited

to basic human behavioral research.”