5 Comments

Ensuring a strong and diverse workforce is a top priority for NIH. To this end, we regularly assess the sex/gender, race, and ethnicity of NIH-supported researchers to better understand the composition of our workforce and participation in our programs. Investigators may self-report their disability status along with these other demographic characteristics on their eRA personal profile. This allows us to learn more about researchers with disabilities in the NIH-supported scientific workforce. Not only is this of interest to NIH, but many in the community have also asked us about this as well. This post presents some of these data.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in August 2022 that just over 1 in 4 adults in the United States have some type of disability. When focusing on data on the workforce, the National Science Foundation (NSF) suggests modest growth in the percentage of academic scientists with disabilities over the past two decades, going from 6 percent in 1999 to 9 percent in 2019. NSF data related to the future workforce also show that 9.1 percent of all graduates earning a doctoral degree in 2019 reported having a disability. These gaps between persons with disabilities engaged within the biomedical research workforce compared to the general population, together with our continued interest in strengthening the workforce, contributed to the creation of a Subgroup of the Advisory Committee to the NIH Director (ACD) last year to identify strategies that support individuals with disabilities in biomedicine. The ACD just approved the sub-group’s report presented at the December ACD meeting, which includes several recommendations for NIH to consider.

Before delving into the data here, please note that we began posting information related to disability status on the NIH Data Book this past February. The data available at this time are limited to the number of principal investigators (PIs) with disabilities supported on certain grants in fiscal year (FY) 2021. More data on disability status are under consideration for release via the Data Book.

Let’s now move to the number of PIs with disabilities designated on NIH applications and awards over time (Table 1). The percentage of PIs self-reporting a disability decreased from 2.0 percent in FY 2008 to 1.3 percent in FY 2022. These data dovetail with other previously published data, such as this 2020 PLOS ONE article by Swenor and colleagues, which 1) indicate that the proportion of NIH-supported researchers reporting disabilities is considerably lower than what is generally found in the U.S. population and 2) formed the basis for our analyses presented here.

Table 1. Number of PIs designated on research grant applications and awards self-reporting a disability: FY 2008–2022

| FY | Number of PIs Not Reporting Disability | Number of PIs Withheld Disability1 | Number of PIs Missing Disability2 | Number of PIs Reporting Disability | Total Number of PIs3 | Percentage Reporting Disability |

| 2008 | 31,976 | 1,753 | 6,242 | 821 | 40,792 | 2.0 |

| 2009 | 34,026 | 1,831 | 3,668 | 798 | 40,323 | 2.0 |

| 2010 | 40,908 | 2,077 | 2,976 | 854 | 46,815 | 1.8 |

| 2011 | 43,048 | 2,104 | 2,857 | 832 | 48,841 | 1.7 |

| 2012 | 43,364 | 2,056 | 3,221 | 804 | 49,445 | 1.6 |

| 2013 | 41,295 | 1,954 | 4,127 | 757 | 48,133 | 1.6 |

| 2014 | 42,525 | 1,988 | 3,951 | 722 | 49,186 | 1.5 |

| 2015 | 42,879 | 2,030 | 3,774 | 679 | 49,362 | 1.4 |

| 2016 | 45,122 | 2,081 | 3,874 | 751 | 51,828 | 1.4 |

| 2017 | 45,573 | 2,052 | 3,887 | 705 | 52,217 | 1.4 |

| 2018 | 46,390 | 2,133 | 3,559 | 734 | 52,816 | 1.4 |

| 2019 | 47,622 | 2,152 | 3,567 | 717 | 54,058 | 1.3 |

| 2020 | 48,294 | 2,143 | 3,815 | 738 | 54,990 | 1.3 |

| 2021 | 50,654 | 2,156 | 4,461 | 751 | 58,022 | 1.3 |

| 2022 | 49,075 | 2,027 | 3,953 | 749 | 55,804 | 1.3 |

1 “Withheld Disability” refers to a PI selecting the option “Do not wish to provide” on their profile for disability status

2 “Missing Disability” refers to a PI not checking any option on their profile for disability status.

3 Includes PIs designated on research grant awards (e.g. R, P, M, S, K, U (excluding UC6), DP1, DP2, DP3, DP4, DP5, D42, and G12).

Interestingly, Table 1 also showed the number of PIs withholding disability status trended upward from 1,753 in FY 2008 to 2,027 in FY 2022. And even though the amount missing in FY 2022 is less than 2008, there were still 3,953 PIs who opted to not make a selection in the last year alone.

Table 2 focuses on researchers self-reporting a disability, specifically breaking it down by the type of disability. The number of researchers reporting a hearing, mobility/orthopedic, visual, or multiple disabilities trended downward between 2008 and 2022, while the number reporting other disabilities trended upward.

Table 2. Number of PIs designated on research grant applications and awards broken down by disability category: FY 2008 to 2022

| FY | Mobility/Orthopedic | Hearing | Visual | Other | Multiple4 |

| 2008 | 227 | 278 | 98 | 146 | 72 |

| 2009 | 229 | 263 | 95 | 148 | 63 |

| 2010 | 242 | 286 | 98 | 163 | 65 |

| 2011 | 243 | 248 | 85 | 190 | 66 |

| 2012 | 235 | 254 | 91 | 159 | 65 |

| 2013 | 228 | 229 | 75 | 167 | 58 |

| 2014 | 205 | 228 | 82 | 163 | 44 |

| 2015 | 195 | 198 | 86 | 162 | 38 |

| 2016 | 194 | 216 | 89 | 196 | 56 |

| 2017 | 175 | 223 | 71 | 194 | 42 |

| 2018 | 170 | 213 | 80 | 221 | 50 |

| 2019 | 176 | 184 | 75 | 240 | 42 |

| 2020 | 171 | 194 | 89 | 248 | 36 |

| 2021 | 173 | 177 | 87 | 273 | 41 |

| 2022 | 167 | 168 | 77 | 291 | 46 |

4 “Multiple disabilities” refers to PIs who have selected more than one disability type.

Table 3 reports the number of researchers who were funded (i.e. designated as PI on an NIH grant) or unfunded (i.e. designated as PI on unsuccessful applications) according to their disability reporting status. Note that this is different from success rate, which is an application (not person) based metric. Similar to table 2, in general, the number of researchers (be they funded or not) reporting a disability went down between 2008 and 2022, while the number of researchers with Other disabilities increased.

Table 3. Number of unfunded and funded PIs: FY 2008 to 2022

| FY | Mobility/Orthopedic | Hearing | Visual | Other | Multiple | No Reported Disability | ||||||

| Unfunded | Funded | Unfunded | Funded | Unfunded | Funded | Unfunded | Funded | Unfunded | Funded | Unfunded | Funded | |

| 2008 | 162 | 65 | 193 | 85 | 57 | 41 | 93 | 53 | 58 | 14 | 27,820 | 12,151 |

| 2009 | 158 | 71 | 180 | 83 | 72 | 23 | 103 | 45 | 50 | 13 | 27,708 | 11,817 |

| 2010 | 182 | 60 | 206 | 80 | 65 | 33 | 121 | 42 | 56 | 9 | 33,368 | 12,593 |

| 2011 | 175 | 68 | 200 | 48 | 67 | 18 | 155 | 35 | 58 | 8 | 35,834 | 12,175 |

| 2012 | 183 | 52 | 177 | 77 | 64 | 27 | 123 | 36 | 51 | 14 | 36,117 | 12,524 |

| 2013 | 176 | 52 | 163 | 66 | 63 | 12 | 132 | 35 | 43 | 15 | 35,782 | 11,594 |

| 2014 | 152 | 53 | 162 | 66 | 62 | 20 | 117 | 46 | 37 | 7 | 35,287 | 13,177 |

| 2015 | 136 | 59 | 148 | 50 | 68 | 18 | 116 | 46 | 29 | 9 | 35,180 | 13,503 |

| 2016 | 147 | 47 | 147 | 69 | 66 | 23 | 141 | 55 | 42 | 14 | 36,474 | 14,602 |

| 2017 | 117 | 58 | 160 | 63 | 46 | 25 | 147 | 47 | 31 | 11 | 36,801 | 14,710 |

| 2018 | 116 | 54 | 153 | 60 | 53 | 27 | 162 | 59 | 36 | 14 | 35,893 | 16,189 |

| 2019 | 128 | 48 | 127 | 57 | 55 | 20 | 175 | 65 | 34 | 8 | 36,840 | 16,500 |

| 2020 | 127 | 44 | 138 | 56 | 62 | 27 | 186 | 62 | 27 | 9 | 37,404 | 16,847 |

| 2021 | 129 | 44 | 120 | 57 | 60 | 27 | 206 | 67 | 33 | 8 | 40,349 | 16,921 |

| 2022 | 125 | 42 | 116 | 52 | 54 | 23 | 226 | 65 | 35 | 11 | 37,565 | 17,433 |

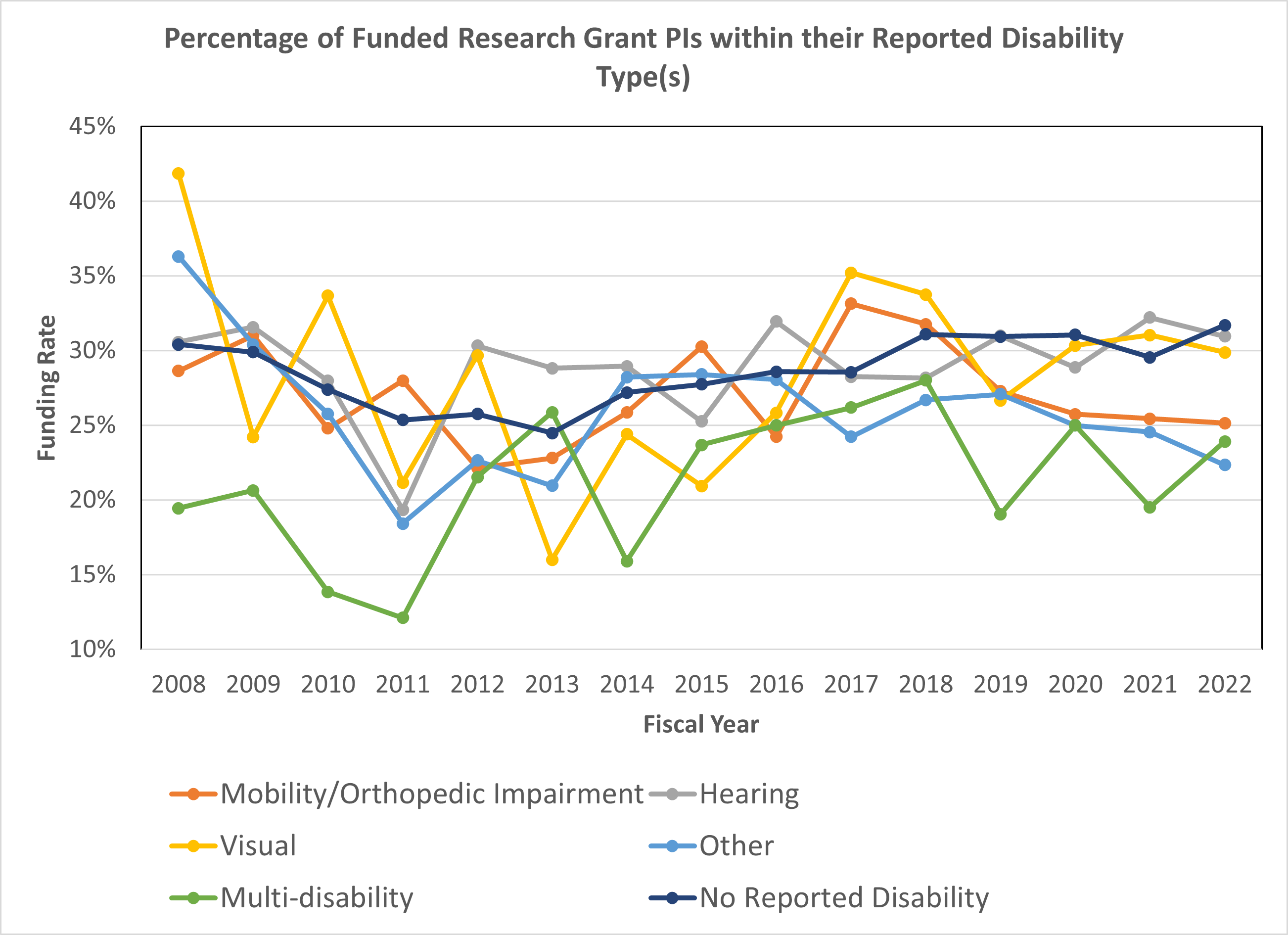

Figure 1 presents the funding rate, which is the percentage of PIs with or without a reported disability designated on an NIH award. The data here derive from the numbers presented in Table 3, and show the same general trends.

A strong and diverse biomedical workforce must be as representative as possible, which also means inclusive of researchers with disabilities. Going forward, we will continue assessing and sharing data related to researchers with disabilities and looking forward to considering the recommendations from the ACD subgroup.

Editor’s Note (March 13, 2024): In my December 2022 blog, I incorrectly characterized published work by Bonnielin Swenor, Beatriz Munoz, and Lisa Meeks as a “2020 PNAS paper” when in fact it was published in PLOS ONE (March 3, 2020). I made this correction in the narrative above. Furthermore, I stated that their paper “dovetail[ed]” with our analyses. I am grateful to Drs. Swenor, Munoz, and Meeks for their detailed analyses of researchers with disabilities from 2008-2018, which not only dovetailed but formed the basis of our analyses that demonstrated continuing declines through 2022. I encourage interested readers to read and, as appropriate, cite their important paper.

Just like in other forms of diversity, it is much more preferable to disaggregate “other”, both in terms of the negative connotation that “othering” has on the individuals reporting these data, but also to help understand how to best support the likely diverse forms of disability represented in this group. It would be nice to know what some of the strategies NIH is considering to improve these numbers going forward. My own experience talking to a PO about qualifying for diversity focused grant mechanism based on my disability status was very belittling – the message was that these mechanisms are intended for racial/ethnic diversity. Training of NIH staff should be a priority.

Agreed. During the period of the supplement I was awarded, I was made to feel inferior by those who have power having substantial NIH grant funding, several R01s. I was unique in I had worked over a decade in the field of disability rehabilitation (even prior to ADA) and had some experience prior to becoming “totally disabled” with a genetic disease. I made a career change into research and searched for a “sponsor”. It ended very badly.

Not having a question specific to disability, which is recognized by the Federal government as a protected category of diversity, is an indication of inferior status and lower priority within any system. Complex gender identity is not a category of diversity recognized by the federal government, yet there are questions on these categories of diversity.

My experience with this, sadly, was abusive as the PI refused to provide the accommodations provided by and funded by the diversity supplement.

The lab treated all my funds as fungible.

They used the supplement funding and other research money I brought into the lab for my own work (I had decades of career experience already) to further other graduate students in the lab, knowing because of the disability that I had fewer to no options compared to able bodied researchers.

Unlike other diversity supplements and researchers, disabled have substantial limitations on location of work, hours of work, access to the workplace and many other concerns.

Because NIH knew little to nothing about ADA and disability accommodation and would not act (even though copious documentation) related to the discrimination against a disabled person under the ADA…. This meant that abuse of supplements by a group, particularly one of power such as major university, has no repercussions.

Giving a lower priority to disabled further enables researchers to abuse and discriminate against disabled researchers.

Having no repercussions for discrimination under the ADA is a risk to all disabled researchers.

For this very reason you are going to have under reporting of disabilities.

I would be curious to know what the percentage of people with self-reported disabilities who have served on Study sections in the same time period is, either as ad hoc reviewers or who have been invited to be members of a specific review panel? It seems to me like you should be able to aggregate this data as well.

As someone with multiple hidden disabilities, it doesn’t surprise me that the number of PIs reporting a disability is decreasing and their funding rates are drastically lower than non-disabled PIs. Why would you stay in science when the odds are so stacked against you? There is very little empathy for hidden disabilities and they are often seen as an excuse for low productivity – I have never seen a comment on a grant that even mentions an investigator’s disability. The NIH’s response to the problem is inadequate and without better education of reviewers things will only get worse.

I would be curious to know if the ACD Working Group on Diversity, Subgroup on Individuals with Disabilities includes any people with disabilities. In research we know it is crucial to include the community in decision making and I hope the NIH is doing this as well.