8 Comments

One year later, the COVID-19 pandemic has drastically affected our individual lives and communities. We have observed disproportionate effects observed in underserved populations, leaving them vulnerable to higher infection and mortality risk. These effects have led to an increased reliance on biomedical researchers and clinicians to offer public health solutions to this crisis. Within the research workforce, early-career scientists may bear the brunt of pandemic-related mitigation measures at institutions and limitations due to inability to be in the physical workspace.

At NIH, we recognized the many ways the COVID-19 pandemic could adversely affect the biomedical workforce, particularly members of underrepresented groups and vulnerable populations. In October 2020, NIH fielded two online surveys to objectively document COVID-19’s impact on extramural research. One survey assessed the perspective of individual research administration leaders at extramural institutions, and the other survey assessed the perspective of the researchers themselves. In this post, we offer a high-level overview of general trends noted within both surveys. This infographic here also describes the outcomes from the surveys.

Background

The former NIH Chief Officer of Scientific Workforce Diversity, Dr. Hannah A. Valantine, spearheaded the development of the survey questionnaires in close collaboration with the Office of Extramural Research, and several other NIH offices. For the Extramural Institutions Survey, which was fielded from October 7, 2020 – November 6, 2020, a research administration leader (vice president for research or equivalent position) was identified from each of the following types of institutions:

- The 1,000 top-funded domestic institutions based on FY2019 NIH awards

- Schools that are part of the Association of American Medical Colleges

- Minority-serving institutions that received grant awards in FY2019

There were 224 participants out of 705 invites (a response rate of 32%).

For the Extramural Researchers Survey, which was fielded from October 14, 2020 – November 13, 2020, the eRA Commons system was used to generate a list that included individual researchers at domestic institutions who logged into eRA Commons within two years prior to the survey, and who identified as having a scientific role (e.g., principal investigators, trainees, sponsors, undergraduate students, graduate students, postdoctoral researchers, scientists, and project personnel). There were 45,348 participants out of 234,254 invites (a response rate of 19%).

Findings

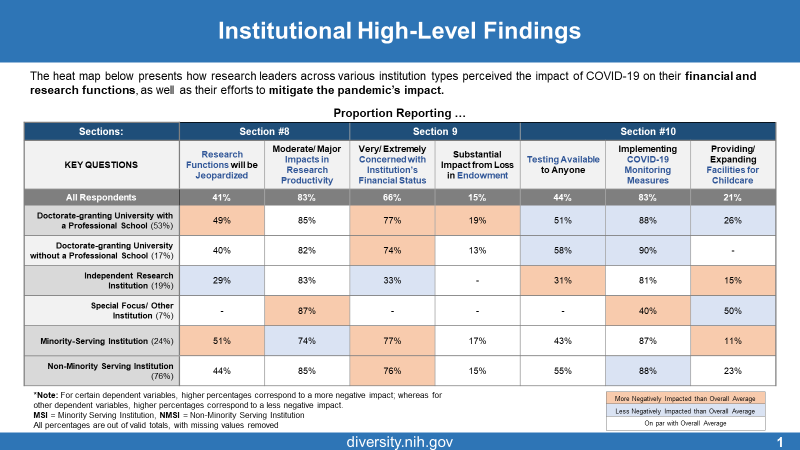

Figure 1 shows the main findings from the institutional survey. The majority of respondents noted concerns about research functions, research productivity, and financial status. Most were implementing COVID-19 monitoring measures, but only a minority were providing or expanding facilities for childcare.

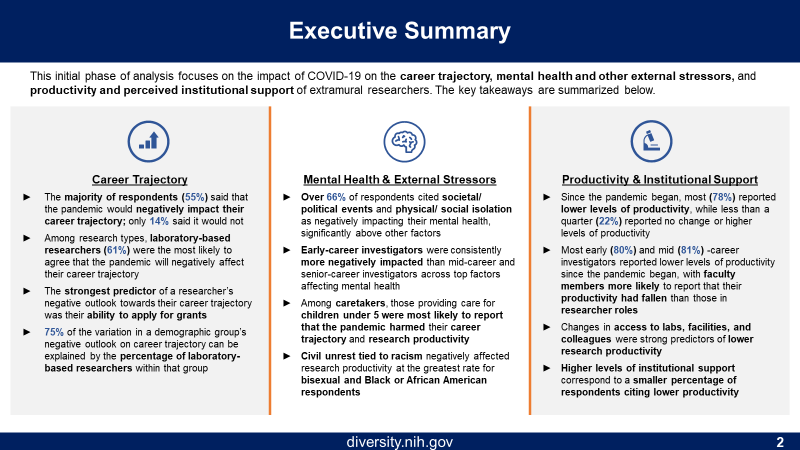

Figure 2 presents an Executive Summary of the extramural researchers’ survey. We focused on three outcome measures: belief that the pandemic will negatively affect career trajectory, concerns about mental health and external stressors, and concerns about research productivity and institutional support.

Figure 3 shows the main findings according to race/ethnicity, gender, and career stage. The left column shows the composition of the respondents (e.g. 69% were White, 53% were women, and 53% were early-career). Early-career scientists and Asians were most likely to report concerns about career trajectory. The vast majority of nearly all groups reported lower job productivity. Women, Hispanics, and early-career scientists were most likely to report concerns about mental health and external stressors. Not quite half of respondents reported that caretaking responsibilities made it substantially more difficult to be productive; we take a closer look at this a bit later. Finally, less than half of respondents felt that their organization was supportive in helping them to remain productive.

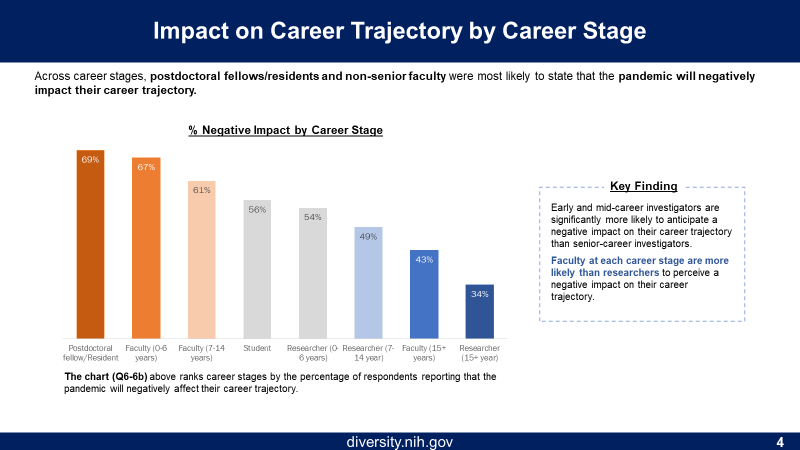

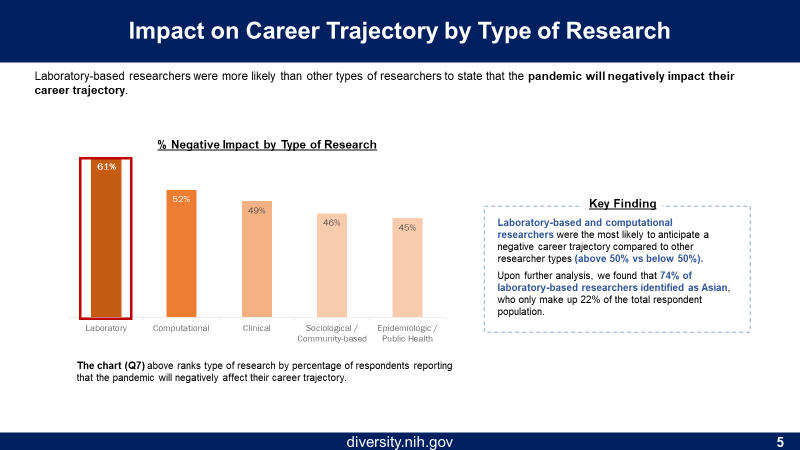

We now take a closer look at concerns about career trajectory. Respondents who were most concerned were in earlier career stages (Figure 4) and conducting laboratory-based research (Figure 5). We used a machine learning algorithm, specifically gradient boosting machines, to determine which of 47 variables were most highly associated with career trajectory concerns. The top variables were by far impact on ability to apply for grants, followed by decreased research productivity, career stage, race, effects of caretaking, and the primary type of research.

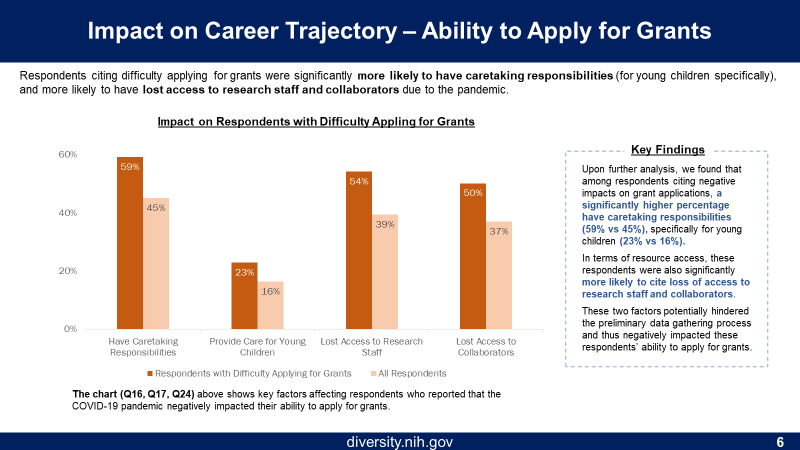

Figure 6 shows the decreased ability to apply for grants were caretaking responsibilities, lost access to research staff, and lost access to collaborators, which together may have adversely affected the ability to generate preliminary data.

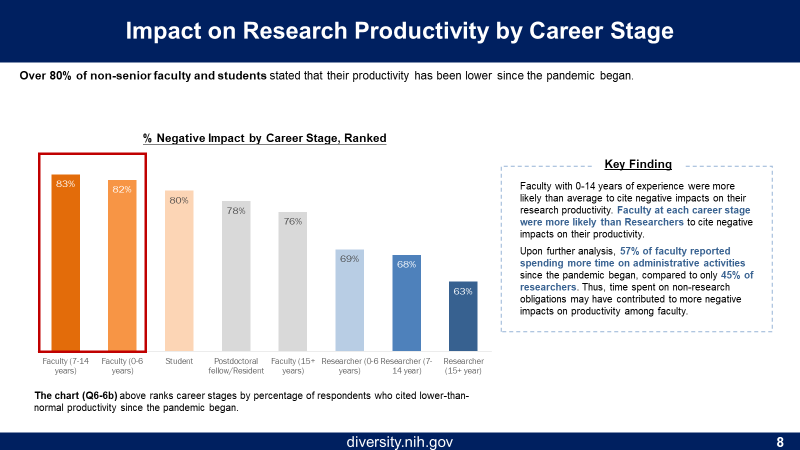

We now move to research productivity. Figure 7 shows that, as might be expected, decreased access to laboratory facilities was among the top predictors of decreased productivity. Figure 8 shows that earlier career stage was also predictive. In a machine learning model, the strongest correlates of decreased productivity were lost access to laboratory facilities, decreased ability to apply for grants, and caretaking responsibilities.

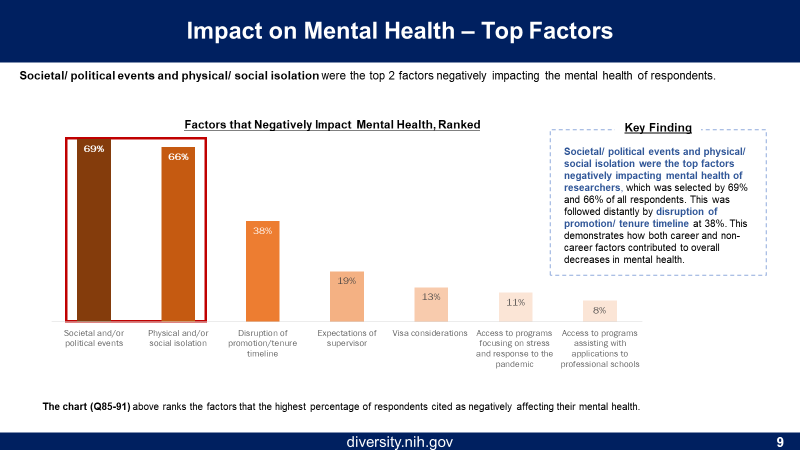

Finally, we look at mental health and external stressors. Figure 9 shows top correlates of mental health concerns. These included societal and political events and physical and/or social isolation.

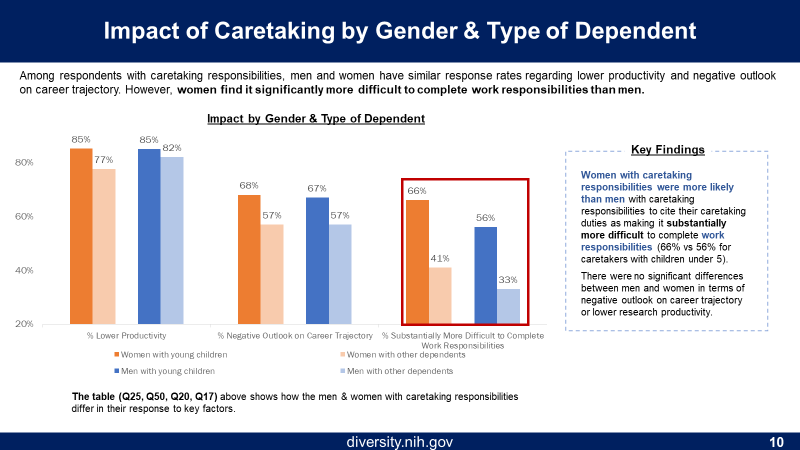

Figure 10 shows more details on caretaking responsibilities. Parents with young children reported the greatest decreases in research productivity, while women were more likely than men to report that caretaking made it substantially more difficult to complete their work responsibilities.

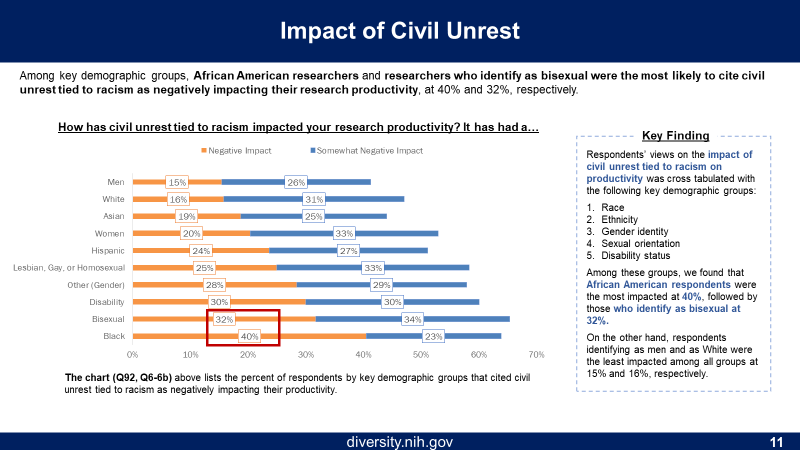

Figure 11 shows data on civil unrest; Blacks were most likely to report that civil unrest tied to racism adversely affected research productivity.

Conclusion

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have been far-reaching. Our survey findings show that the scientific workforce has not been immune to its effects. It is clear the NIH-funded community of extramural researchers has experienced inequities in several domains, with early-career researchers and those with caregiving responsibilities most affected.

NIH has already begun taking preemptive actions for investigators early in their careers, recently issuing a guide notice detailing opportunities for extension of Fellowship (F) and Career Development (K) awards impacted by COVID-19. NIH has also allowed investigators affected by COVID-19 (e.g., university closures) to submit requests for an extension of Early Stage Investigator (ESI) status through eRA Commons.

We will continue to analyze these data and high-level findings will be shared with the extramural research community in the coming months. Using these and other data as they become available, NIH will maintain its focus on evidence-based actions to foster inclusive excellence within the scientific workforce, to better support the health of our entire population.

I feel like the one issue not addressed in this survey was the direct financial impact of the pandemic. Being in Ohio, we were effectively shut down from mid-March to mid-August, although some COVID work was allowed from mid-June on. However, we still had to pay all our personnel for that entire period, without any institutional support whatsoever and there has been no recognition of that by NIH – losing 5 months of a 4-year R01 is a huge hit. I am not complaining about paying my people as it was the right thing to do, but NIH might have helped cover those costs.

The financial impact is particularly painful for small labs, which may also contribute to gender disparity.

Strongly concur with Ian. The non-science world received various forms of compensation to make up for lost jobs and wages, etc. While we had the capacity to maintain employment, the end suffering from insufficient funds to complete objectives and aims is fundamentally a major loss of investment by funding agencies, and a potentially huge blow to individual investigators’ research and career objectives.

We had the capacity to maintain employment, the end suffering from insufficient funds to complete objectives and aims is fundamentally a major loss of investment by funding agencies, and a potentially huge blow to individual investigators’ research and career objectives.

The one issue not addressed in this survey was the direct financial impact of the pandemic. Being in Ohio, we were effectively shut down from mid-March to mid-August, although some COVID work was allowed from mid-June on. However, we still had to pay all our personnel for that entire period, without any institutional support whatsoever and there has been no recognition of that by NIH – losing 5 months of a 4-year R01 is a huge hit. I am not complaining about paying my people as it was the right thing to do, but NIH might have helped cover those costs.

COVID-19 had an adverse impact on many of us. Recently I got recovered from COVID19. Rightly someone has pointed out the fact that The financial impact is particularly painful for small labs, which may also contribute to gender disparity.

The non-science world received various forms of compensation to make up for lost jobs and wages, etc. While we had the capacity to maintain employment, the end of suffering from insufficient funds to complete objectives and aims is fundamentally a major loss of investment by funding agencies and a potentially huge blow to individual investigators’ research and career objectives.

The financial impact is particularly painful for small labs, While we had the capacity to maintain employment, the end of suffering from insufficient funds to complete objectives and aims is fundamentally a major loss of investment