37 Comments

A Look at the Latest Success, Award and Funding Rates…and More

We frequently talk about the different ways of analyzing NIH funding. Let’s revisit this topic so I can provide you with the latest numbers. As a reminder,

• Success rate describes the likelihood of a project or an idea getting funded, rather than of the success of the individual application submission.

• Award rate describes the chance of an individual application being funded and is the number that more closely reflects institute and center paylines (which can vary significantly from one institute or center to another).

• Funding rate reflects the number of investigators who seek and obtain funding. Each principal investigator (PI)* is counted once, whether they submit one or more applications or receive one or more awards in a fiscal year.

Now let’s look at the latest data for NIH as a whole. The chart below shows modest upward trends for fiscal year (FY) 2014 compared to 2013. NIH received 51,073 research project grant (RPG) applications, out of which we funded 9,241, resulting in a success rate of 18.1 percent. When we look at award rate, which accounts for resubmissions that came in during the same fiscal year, the application count increases to 54,519 resulting in an award rate of 17.0 percent in 2014. And if we look specifically at numbers of PIs, we see that in FY 2014 we funded 9,986 PIs out of 39,809 total investigator applicants for a funding rate of 25.1 percent.

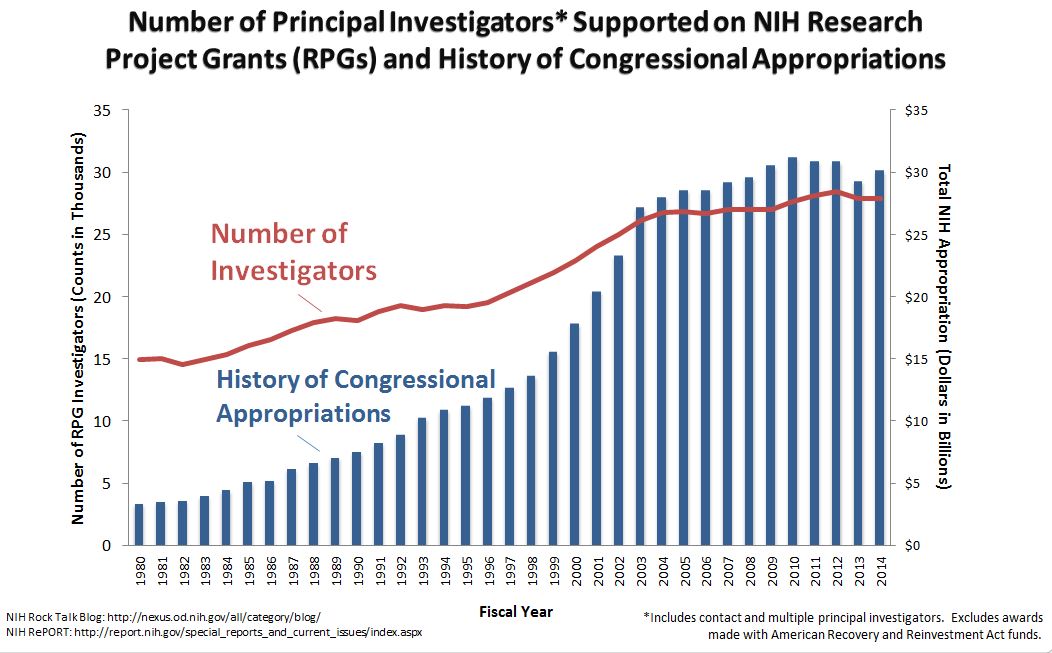

Not surprisingly, we see that since the end of the doubling of the NIH budget in 2003, success, award, and funding rates have dropped. But despite the challenging times, as you can see from the graph below, the number of PIs supported by competing and noncompeting grants per year has increased considerably since 1980—from over 15,000 to slightly over 27,000—closely tracking the pattern of the overall NIH budget. The number of investigators rose to an all-time high in FY 2012, after which it fell, likely related to the sequestration that significantly reduced NIH’s budget. While NIH funding levels were partially restored in FY 2014, the number of PIs remained at 2013 levels.

So what are the take-away messages? Success, award, and funding rates track closely to the NIH budget. And clearly, the NIH budget is not keeping pace with demand; as a result, the success, award, and funding rates are at historically low levels. However, more applications are being submitted and more PIs are being supported now compared to 15 years ago.

I know many of you like to data dive, so we have made these files available to you on RePORT. We will continue to monitor these rates, and the impact our policy changes have on these numbers.

An obvious caveat of this analysis is that awards are typically cut and modules have not been increased in many years.

$250K today (typically cut to<$200K by programmatic review) do not support the same today as 15 years ago. As a result, everybody needs to submit more grants to subsist.

Plus of course, with paylines at 9% for certain institutes, getting a grant funded has become an exercise of throwing darts until something hits the target.

Further, it converts well-trained researchers to full-time (or overtime) grant writers, having less experienced people do all important experiments.

Of course, awards made through the nebulous select pay process raise the success rate. Care to recalculate the numbers based on awards made solely by peer review and not by the whim of an administrator?

You forgot to add an administrator who is a failed scientist. Sorry, but how is it that POs, who have NEVER held funding, published few papers and rarely (if ever) held faculty posts, are fit to make decisions about funding that don’t align with study section scoring. The NIH continually moves the bar to force greater transparency on the part of its scientist (new biosketch, PMCID etc) but yet the route to funding becomes more obscure and subjective each year.

Agree with CD0, my places are well below 10% at times in the last 5 years. Are SBIRs the reason for this mean funding rate? Can we get a scatter plot to explain the disparity that seems to exist?

What I would like someone to explain is the following. As a member of a standing NIH study section, I know that we are funding at close to the 10% rate. I also know that this applies to all the grants we are asked to review – so both original and revised submissions. I know that most other institutes are funding at similar rates to ours, but to come up with an average of 17% as posted by Sally, some of them must be funding at rates >30% of all their applications. Is that correct? Which institutes and/or grant opportunities. Are we including early stage fellowship grants? What gives?

The tables are using data on Research Project grants, which include R01, R03, R15, R21, R22, R23, R29, R33, R34, R35, R36, R37, R55, R56, RC1, P01, P42, PN1, U01, U19, UC1. While we have not published detailed data on award rates by IC or program, you might be interested in exploring the RePORT Funding Facts tool, which will allow you to look at success rates by Institute and Center, type of grant program, etc.

Does “applications reviewed” include unscored grants?

Yes.

That was my question, too.

” more applications are being submitted and more PIs are being supported now compared to 15 years ago ”

This is not corrected for population or GDP growth. There are simply far more people and more researchers in the US than 15 years ago. The percent of the GDP and of the federal budget going to research has declined significantly in recent years.

The denominator of success and award rates is “applications reviewed.” Some prior NIH publications have tallied only applications discussed at review, rather than those submitted for review (discussed + not discussed). The difference between the two methods would be roughly two-fold. Which is used here?

Applications that are not scored are included as reviewed applications (reviewers have still looked at the applications even through they were not scored).

CD0 is correct on all points. I am at the point of my career when I should be at peak productivity, but here I am at 10 pm with less than 5% of my real effort hours (~160% FTE!) integrated over time actually devoted to research. I am filing noncompetes, writing new grants, applying to dozens of private foundations to fill in the gap that NIH cuts create, complying with onerous animal welfare regulations, devoting lab meetings to RCR rather than more urgent and interesting matters, trying to find the g..d… PMCID numbers for recent papers, reformatting my biosketch, patching together equipment with paperclips and rubber bands because I can’t afford service contracts, AND serving on a study section. On top of that, the brightest students and fellows see how little time I get to do what I actually love, and conclude (very reasonably) that they don’t want to follow my path. The not-so-bright end up in our grad program where I have to spend hours convincing each one that they should welcome constructive criticism, not cry about it.

It is actually very depressing to think about what I could be doing just a few steps away in my lab, and what I am forced to do instead in this tiny office at this late hour.

I wish NIH would do SOMETHING once in a while that decreased the non-research tasks of my day, but nooooo – tomorrow morning I have to hike across campus to personally attend NIH-OAW mandated training in how to kill a mouse by cervical dislocation (what do they suppose we’ve been doing for the past 30 years, drop-kicking them against the wall ?). I’d like to extract something from the rodent at OAW who created a rule that I have to do that.

I agree completely – I spend a huge amount of time doing all of the above plus teaching (this is academia, after all), peer-reviewing manuscripts, preparing modified manuscripts for publication (it’s harded than ever to get something published, yet study sections still score ‘productivity’ by directly comparing PI’s without recognition of different levels of financial support from multiple sources).

Actually, I rather like teaching, and neither my university nor NIH requires me to do it, so I didn’t include it on my list of complaints. However, I am required to support 80% of my salary through grants. Now here’s where I have a major complaint: NIH-mandated RCR training. Despite everything we are supposed to teach about integrity and the honest reporting of data, I might specify that any given grant supports 25% or maybe 40% of my salary, but what a lie!! Any individual project probably gets no more than 2% of my effort. The only way a grant-funded project could ever get 25-40% of my effort is if you count all the time spent to GET the grant in the first place!!!

Yeah – so that’s what I teach in our RCR sessions – what a lie we are all forced to live.

This also summarizes my life, with the exception that our IACUC does not allow cervical dislocation and I need to be trained in the use of CO2 containers.

I guess the “more applications are being submitted and more PIs are being supported” is supposed to be encouraging. It’s nice that the NIH wants us to feel encouraged – but the fact remains that by any of the three measures, rates are the lowest they have been in *25 years*. Unless Congress increases the NIH budget, or the NIH realigns priorities to fund more individual R grants and fewer “big science” big-ticket items, it will be hard to feel encouraged.

Dear Sally Rockey, Is it possible to get links to the actual data used to make your two very informative figures. I did find what I think is the Congressional Appropriations data in http://www.nih.gov/about/almanac/appropriations/index.htm. So many thanks for these wonderful analyses.

We posted the data files on RePORT (this is a direct link to the table).

NIH will need to either increase the funding rate or pass some regulation to stop funding the Universities who are relying heavily on NIH funding to run their institiution. In addition, to be fair no PI should hold more than 2 RO1 at a time. Lots of PI just waste federal funding when they have many R01s. Special tax reforms should be made to ask vendors to supply research items to University at a discounted rate.

There is really no need to waste limited funding on program if the University does not cover the salary of the PI and the coworkers. The indirect cost spending details should be provided and strict auditing should be done on the how indirect cost was spend at each University. New auditors needs to be hired to performed peiodic check on indirect cost spending. Accountability to the federal budget is the key to maintain this fragile NIH budget. Government simply do not want to spend more money at this point on research and this is the best option is to learn innovative ways to save NIH research money. For new investigators there should be signficant linency to build their career in science.

Well put, ” getting funded has become an exercise of throwing darts untill something hits the target”. However, the target is not defined, so getting funded is more like throwing a dice in the dark and hoping that somebody will see the number 6.

Can a progressive country like the USA afford to throw darts or dices? We are wasting billion of dollars to rewrite grants, to do experiments for preliminary results which may not be pursued, to pay administrators to generate budget and submit grants, and all these at the expense of doing a good research. No surprise more and more published work is retracted.

I am afraid USA is sinking.

Before the first graph, this paragraph contains some rather interesting sub-text… NIH received 51,073 research project grant (RPG) applications, out of which we funded 9,241. And if we look specifically at PIs, we funded 9,986 PIs out of 39,809 total investigator applicants

One possible take home from this, is that 9,986 PIs got 9,241 grants, which hints strongly that mutli-PI grants made up a reasonable chunk of the funded proposals.

The other way to parse this, is to say 39,809 investigators applied for 51,073 awards, so the PI/grant ratio on the application end was 0.779. On the funding end however, the PI/grant ratio was (9,986/9,241) = 1.081. This suggests that a much greater percentage of multi-PI proposals were funded. If NIH has separate numbers for Success/Award/Funding on multi-PI vs.single-PI proposals, that would make for an interesting comparison.

You may want to check out our post on How Do Multi-PI Applications Fare.

Funding at “25%” is rather forward-looking and quite distant from the experience in the field. Will miss the boss

The above graphics do not seem to support the conclusion that research spending tracks NIH budgets. Look at the period from 1993 to 2003. NIH funding more than doubled, but award, success, and funding rates were nearly unchanged, perhaps even down at these points. Furthermore the number of investigators increased by, perhaps, 50%, so it is not a matter of disproportionately more investigators diluting the pool of resources. I don’t know what the demands on the NIH were during this period, but the data provided in this article do not seem, to support the “take-away message”.

Does NIH have any data on what percentage of research funded actually gets commercialized and used for patient care?

A study done internally at Rice University found that it is less than 1%.

Could the reason for this be that NIH is allocating 2.5% of its budget for commercialization efforts via the SBIR and STTR programs? Also the SBIR research is never funded to viability, leaving many companies in the ‘valley of death’ to die.

The NIH should reevaluate its mission, so that discoveries at universities have a robust pathway and funding to commercialization.

The funding for the SBIR -STTR program should match the funding for basic research. Otherwise a lot of great discoveries will never see the light of day.

<1% commercialization success rate is really a failure of the way business is done at the NIH and a very poor return on investment of our tax dollars.

PI funding rate. What does that include. Co-PI on an R21? a postdoc on an F32? SBIR. Faculty running a R56 as a co-PI? I would ask what qualifies as “support” and what is considered a PI.

When we talk about PI funding, we are only talking about the principal investigator or those designated as multiple principle investigators on the award.

An excellent comprehensive article has just been published on line in the June 29 issue

of eLIFE…..This article, from a group at the University of Wisconsin/Madison addresses many of the current problems of NIH funding of biomedical research in America. It represents a lot of thoughtful and time-consuming work not only by this group but, in addition, scientists who have written on this topic before, who joined

the group in formulating the document, eg. Kirschner, Tillghman, Alberts et al. The key

parts of the document are the recommendations for addressing the current funding

problems. The article should be required reading for all administrators at private and public

research universities and institutions, and it should be read by all NIH administrators from

the top down, and graduate and post doctoral students in the biomedical science.

Thanks for these interesting data, Sally. Might you please provide the % of applications funded out of those submitted, broken down for each gender, for each of the R mechanisms?

A caveat, to the the “obvious caveat” is that more investigators are getting cut out (and only more recently) because the number of investigators applying has also increased, and that each investigator is now asking for more in one grant than they did back in 1999~2001, when the funding success rate peaked. This intimates that a few select investigators are getting large chunks of money, and it may be a way that NIH is mitigating risk, which is unfortunate.

“more applications are being submitted and more PIs are being supported”

Thus statement is true but terribly misleading. A simple calculation with these data

http://report.nih.gov/NIHDatabook/Charts/Default.aspx?sid=0&index=1&catId=13&chartId=124

Shows that there has been a 22.9% increase in awards since 1998 (e.g. from 7518 in 1998 to 9241 in 2014) BUT co-occurring with this increase is a 111% increase in applications (e.g. 24,151 in 1998 to 51073 in 2014). This translates to # of applications outpacing funding but almost 5 fold (4.86 to be exact). It is irrelevant more people are applying and there are more awards, the ratio in the rate of change in award to applications is far more informative about trend.

Thanks for these interesting data, Sally. Might you please provide the % of applications funded out of those submitted, broken down for each gender, for each of the R mechanisms?

I always appreciate the statistics and graphs provided on these pages. Regarding this discussion, it would be interesting if, instead of NUMBER OF INVESTIGATORS, the NUMBER OF UNIVERSITIES receiving funds over the years were listed in a graph of this sort. My guess is that fewer and fewer universities are getting more and more of these funds.

The related problem with NIH funding is the huge amount of IDC paid to universities. It drains a LOT of money from the NIH budget, and at some universities, none of it goes back to the PI or department to support the research, which I thought was the idea in the first place. University administrators always say it is for the lights/heat/water but those bills do not add up in anyway to 50%+ IDC rates that are typical these days. This is particularly the case if a few universities are getting most of the IDC funds. Maybe these data have been presented somewhere, but I haven’t run across them yet. thanks…

I agree with most of what has been said above. However, I would like to encourage a call to action. Take the energy I feel pulsating through these posts and email your Senators and Representative about the importance of research funding! Better yet, request a meeting with them (they are home in August, make them work!) or their staff and explain the importance in person. Hearing it from an actual scientist is so motivating.

While there are some things the NIH can do to help here, most of the problem is lack of funding, and ‘we the people’ need to put the screws on our Congresspeople.

I wanted to write my comment in a post from a previous time, but the entry would not work, so I am posting here, because my story is important for all women to hear, as well as those in any position of providing grants.

So, here it is:

Here it is 2016 I and found this blog. I am the “poster woman” for a good researcher who took time off her work for the sake of the wellbeing of her small children. This is a natural instinct, and should never interfere with a career. The field is unforgiving, and labeled me a “stay at home mom” for life. I have been criticized for this decision by other women not in my situation, and patronized by men. After seven years of producing high quality human beings, my best experiment by the way, I searched for opportunities only to find doors slam in my face. The best I could find were adjunct teaching position. Research overlooked that fact that I was well published, capable of writing grants, and had performed cutting edge molecular research that aided in the advancement cancer therapies. After all, I was a woman, a “stay at home mom.”

I continue to fight this fight. I am getting older, and now there are prospective employers who look me in the face and actually say, “Really, how long do you expect to stay here if you did get the job?” What?????? Is that sex discrimination? Is it age discrimination? I think it’s a little bit of both. This would not have been said to a man. Men would never have taken a hiatus to tend to their children. A man would have been hired regardless.

I have been searching for a full time position in research or academia going on ten years now. I am a fierce advocate for women in science, and when I get to speak to any of my female students during the adjunct teaching positions, I sit them down and give them the harsh truth. We have to fight every step of the way, and it should not be this way. Something needs to change. The old big boys need to step out of the way. There should be NIH grants set aside for people like me, grants only given to women who return to science after time spent assuring that their children are cared for and nurtured.