12 Comments

Guest post by Noni Byrnes, Director of the NIH Center for Scientific Review, originally released on the Review Matters blog

The scientific peer review process benefits greatly when the study section reviewers bring not only strong scientific qualifications and expertise, but also a broad range of backgrounds and varying scientific perspectives. Bringing new viewpoints into the process replenishes and refreshes the study section, enhancing the quality of its output.

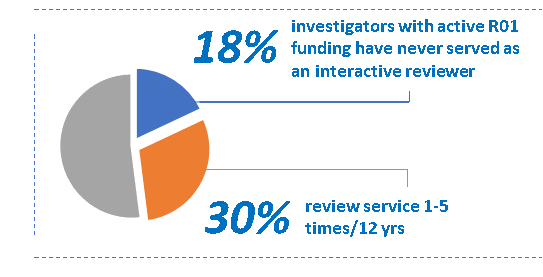

In this context, CSR recently removed the requirement to have at least 50% full professors on committees. This had sometimes led to a misguided attempt to “do better than the metric” by aiming for a committee of all full professors. We are now encouraging scientific review officers (SROs) to focus on scientific contributions (demonstrable in a range of ways, e.g. recent publications, R01 or equivalent extramural funding from other sources, etc.), expertise, and breadth instead of trying to meet a career-stage metric. Our goal is to achieve a balance of perspectives by including a mix of qualified senior, mid-career, and junior scientists on study sections.Our data show that this can be achieved, as we have not exhausted the pool of eligible reviewers. Using R01 grant funding as a rough indicator of “qualified to review” we looked at interactive (i.e. excluded mail review) review service records of R01 awardees. As of January 1, 2020, there were 22,608 individuals with active R01 funding. Of these, 30% (6715) have served one to five times, and 18% (4074) have never served as a reviewer in the last 12 years. Of those who have served only one to five times over 12 years, 26% are assistant professors and 34% are associate professors.

In an effort to facilitate broader participation in review, we are making these data available to SROs and encouraging them to identify qualified and scientifically appropriate reviewers, who may not have been on their radar previously. In another step to broaden the pool of reviewers, we will launch a web page this spring through which scientific societies can recommend qualified reviewers.

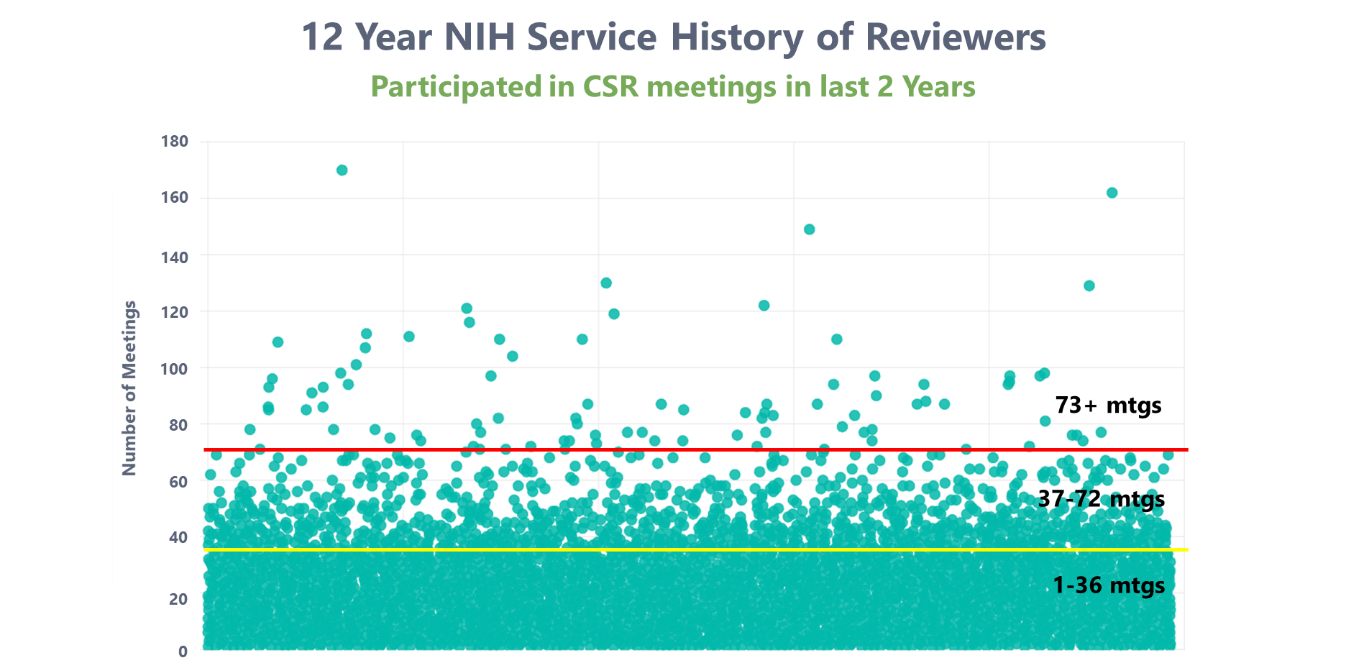

We greatly appreciate the generosity of reviewers who contribute to the scientific community by freely giving their time to review NIH grant applications. However, one aspect of broadening the pool of reviewers is to avoid excessive review service by a small fraction of people, which can lead them to have a disproportionate effect on review outcomes. We are looking into issue of undue influence, or the “gatekeeper” phenomenon, where a reviewer has participated in the NIH peer review process at a rate much higher than their peers, and thus has had a disproportionate effect on review outcomes in a given field. Below is a plot examining the service records of all 24,642 reviewers who served as reviewers (in a capacity other than as a mail reviewer) for CSR within the past two years. Each dot represents a reviewer’s number of meetings for the NIH over the last 12 years.

Below the yellow line are reviewers who have served an average of once per round for 12 years—these make up 94% of the total pool and include the vast majority of the reviewers used. Between the yellow and red lines are reviewers who have served an average of twice per round for 12 years, 5% of the pool. The small number of reviewers above the red line have served an average of 3 times per round (9 times per year) for 12 years; this is the sort of excessive review service that raises concerns about undue influence.

To actively manage undue influence, we have asked SROs to check review service records prior to inviting reviewers. In addition, based on our analysis of the reviewer service data and the unanimous recommendation of the CSR Advisory Council, we are discontinuing (NOT-OD-20-060) the “recent substantial service” policy that extended continuous submission benefits to those who served 6 times over a period of 18 months (6 times in 5 rounds). This policy, established in 2009 with the best of intentions to incentivize review, has led to the unintended consequence of encouraging excessive ad hoc review service within a short time frame. Implementation of this change will be gradual, maintaining eligibility for those reviewers who have already served, and honoring commitments to those who are serving now and will continue to serve through June 30, 2020, the end of the current eligibility period. Continuous submission eligibility for appointed members of NIH study sections and committees will not change. Policies surrounding late submission of applications also are unaffected (NOT-OD-15-039).

CSR’s mission is to provide a fair, independent, expert, timely review – free of inappropriate influences – so the NIH can fund the most promising research. CSR continues to work to broaden its scientific review groups because a diversity of expert perspectives better allows identification of potentially high-impact research, which benefits all of us.

If you haven’t served recently, we hope you will do so if asked.

That is a great initiative. So far I have asked everyone want to play role in the Grant Review process.

Given the fact that now grant review process can be done without physical presence, we can design bigger review panel and “grant discussion can go for days instead of just one day and instead of just 50% grants, we should discuss all 100% grants”.

Grant involve important tax payers’ money, so every grant should be scrutinized from several angles and prospects.

This initiative should be expanded even more for study sections examining SBIRs that focus on innovative product development to cure diseases. These studies sections should include an equal proportion of academics, educated patient advocates, educated citizens, and educated company executives to broaden the perspectives of what should be funded.

Having “permanent chartered” members on study sections is a recipe for corruption even if there are so-called term limits (4-5 years is way too long). Such corruption often goes under the radar of NIH officials. Applicants are gaming the system by inviting these chartered members, developing relationships with them, bestowing gifts (honoraria) on them, and in some cases even contacting them before review of applications. Constantly bringing in new reviewers, and permitting old ones to serve only on one or two meetings, is the best antidote to fight this corruption.

Any entity that focuses on anything other than ability is doomed to fail. The quality of the review process had gone down hill over the past 7 years like a Soapbox Derby car and it has picked up speed over the past several years. It is not hard to fix that problem, and this is not the way to do it. Embracing failure for the sake of being PC is not a recipe for success.

A source of reviewers that could be more utilized is retired faculty and staff.

totally agree. quality and excellence in science is being compromised for the sake of PC. unqualified reviewers. i am all for inclusivity but just look at the credentials of some of these “diverse” reviewers. unqualified ESI PIs who get a huge break but are completely ill-prepared. wait 5-10 years and see what papers they produce and whether they are still PIs. biomedical science in US is heading toward mediocrity while China, Korea, Germany are investing in excellence. the unelected NIH bureaucracy has utterly failed the US taxpayer but no one will hold them to account and they will do fine with their FERS

How do you define ability in this setting? Wouldn’t it be possible to assure that reviewers have the abilities required before starting their terms, while also making an effort to broaden the reviewer pool?

I received my R01 in year 3 of my independent position, before I was aware of the ECR program. I have never been asked to serve. Importantly, my request to serve have been rejected twice for not having multiple (10) papers per year – a task difficult for new investigators, especially those who don’t do a high throughput technique with multiple collaborations.

While I am always encouraged to hear of NIH efforts to increase the number of new reviewers, I am, on the other hand, challenged to find genuine, transparent opportunities to do so. The last time I reviewed for NIH has been several years and I continue to seek opportunities to review. I also know of several scientists and researchers, who are diverse regarding background and areas of expertise, who would like to be afforded the same opportunities.

Who should be contacted to submit CVs and letters of interests to review?

Where can the process for review consideration found?

Thank you.

Please see our page on becoming a peer reviewer: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/peer/becoming_peer_reviewer.htm

Recruiting more reviewers is on the surface a good idea. However, recruiting good reviewers is the challenge. Too many young reviewers do not take the time and energy needed to properly review the grants or worse yet, only care about the idea and potential impact. Too many times I have sat on a study section only to hear a reviewer say that he scored based on the idea of the grant and did not realize one of the aims had already been published 2 years ago, that a grant is not innovative because the PI uses standard techniques (e.g., western blotting, flow cytometry, xenografts, etc.) to test the hypothesis, or the PI has been an expert in the field for 20 years and made seminal discoveries but that the grant does not contain a CRISPR screen or a PDX model so he gave it a 4. Too many reviewers do not understand how to review, what the different scored sections are, and that sustained productivity means something. Grant reviewing is hard work that requires training and unfortunately, today too many young scientists need lots of training to be good grant reviewers. Make sure this happens before opening the floodgates or NIH will have made the problem worse.

I will never forget that I was reviewing for the AHA and we had to fill a form with the number of hours we had worked on the reviews. I had 40 hours, I glanced to the side, my colleague had 2 hours! Right there, I understood the difference between good and bad reviewers.