43 Comments

and Extramural Research Integrity Liaison Officer

It is a priority to us to continue to engage with the community about what constitutes a breach of NIH peer review integrity – including, but not limited to:

- A reviewer sending grant applications to their postdocs to write their critiques

- Someone revealing that they reviewed a particular application

- A reviewer disclosing how another reviewer scored an application

- A principal investigator (PI) approaching a reviewer at a scientific conference to discuss her/his institution’s application in which s/he is designated as PI

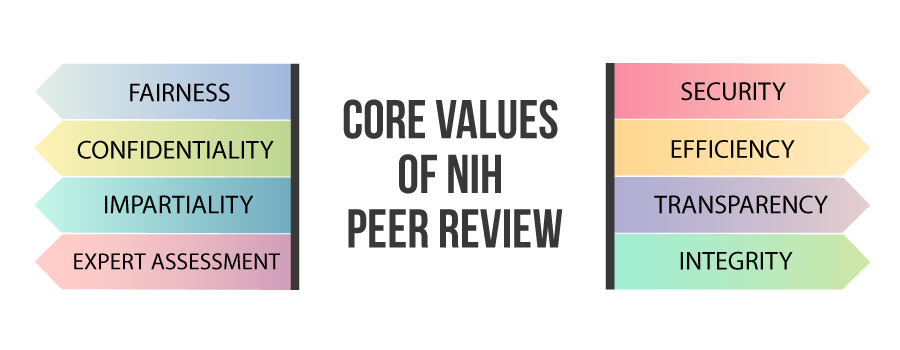

Yes, each of these constitutes a breach of NIH peer review integrity. The NIH defines a breach of review integrity as any violation of a core value of NIH peer review:

In previous communications, we outlined NIH policy on confidentiality of the peer review process and the responsibility of all those involved to uphold integrity. We also outlined potential consequences of breaches of review integrity, such as terminating the review or Council member’s service in peer review, pursuing a referral for suspension or debarment, or other possibilities that could result in criminal penalties. Maintaining review integrity continues to be a matter of great concern, not only to the NIH but to the entire biomedical research community.

Our attention to peer review integrity has been heightened with our growing awareness of the scope and impact of breaches, including those related to undue foreign influence in peer review. In response to these concerns, for example, Dr. Collins issued a Statement on Protecting the Integrity of U. S. Biomedical Research, which highlighted, among other issues, the sharing of confidential information by peer reviewers with others, including in some instances with foreign entities, or otherwise attempting to inappropriately influence funding decisions.

We continue to learn of other problematic conduct – reviewers sharing applications with others without first obtaining permission from the NIH Scientific Review Officer (SRO); reviewers asking others to write reviews for them; PIs contacting or attempting to contact reviewers prior to study section meetings in attempts to influence the outcome of review; and reviewers and PIs sharing confidential information with each other.

Review integrity concerns not only compromise our NIH peer review process but also raise other questions and potential concerns, including about an individual’s authority and responsibility as a designated PI on NIH applications and awards. Moreover, review integrity concerns lead to concerns that the relevant institution(s) may not be fully cognizant of their responsibilities and of the potential consequences of integrity breaches, which are leading to violations of the terms and conditions of their NIH awards.

It is important to us to remind the community that together, we must take action to uphold integrity in peer review. For example, among other actions in response to a breach of review integrity (NOT-OD-18-115), NIH may request that officials of a grantee institution review the actions of their personnel who are involved in a breach and are the PI(s) on NIH grant applications and awards, and to respond in writing, addressing any impact on such applications and awards, and confirming any responsive action(s), such as requesting NIH’s approval for a change in PI status. We are pleased that many institutional officials have taken our concerns seriously, helping convey the message that working together, we will hold people accountable for inappropriate actions, and that working with us will be responsible and accountable stewards of federal funds.

This is not a parlor game of WhoDunIt. When the core values of peer review are compromised, funding decisions may be based on improper or inaccurate information; proprietary information may be compromised; the public may lose trust in science; and patients in clinical studies may be harmed. We thank those of you who have informed us of possible problems – even though we may not be able to share confidential specifics with you, we can take and have taken action. And we thank the tens of thousands of individuals who serve in NIH peer review each year with honesty, respect for the process, and desire to support the common good.

Stay tuned. In coming months, we will present a series of case studies in the Open Mike blog to stimulate further dialog on these issues.

If you see something, say something.

Michael S. Lauer, MD

Deputy Director for Extramural Research

Sally A. Amero, PhD

NIH Review Policy Officer and Extramural Research Integrity Liaison Officer

The reminder about PR integrity is well appreciated and necessary. This said, the “blind” design is one-way, meaning the reviewers do know the applicant. This makes the review process intrinsically biased, and subjective.

I agree … the review process MUST be blind for both parties to avoid conflict of interest.

This is impossible. A reviewer cannot give a score for the Investigator review criterion without knowing who are the PIs and Co-Investigators. Furthermore, a simple glimpse at the references cited will give you a good idea of who is the PI.

It is not impossible. The Department of Defense has a anonymous review process that works quite well. The program officers/NIH staff should be able to determine whether an institution is able to support the research. Peer reviewers might also base their score on investigator from a list of articles (whether they are first/last author, journal name, year of publication) without the list of authors and titles. There are a number of ways to do this, it just might take some imagination and creativity. As it is now, the applicant can usually figure out from the study section roster who reviewed their grant. What about the potential for retaliation from the applicant? Especially in a small subject areas. Some of us have had experience with this.

That would certainly be a radical departure from the current review system. It would mean dropping the Investigator and Environment criteria, altogether. Still, in my field (pain physiology) I will be able to guess with a high degree of confidence who is the PI, just based on the subject and the references cited. Everybody cites their work more. Regarding a “blind” list of references, it will be either impossible to judge because you could not read the article, or you will be able to find the authors in PubMed.

I do agree that most of the time it is possible to guess who the reviewers are. That means that the system is not blind in either direction.

It is entirely possible. The reviewers should only be scoring the “Background and Significance” and “Approach” sections. Blindly. The rest can be scored as a “Go/No Go” by the NIH program director, as a simple follow-up for successful applications only. It is a simple matter to establish if the investigator has the required credentials, facilities and equipment, or not.

yes, a two-stage review where reviewers evaluate Background, significance, approach blindly and NIH establish the credentials of the applicants (productivity, environment and resources) would be a great system.

I totally agree with this idea. I would go even further and eliminate the inclusion of productivity in the evaluation. Science is a quality, not a quantity process. Someone can have a revelation like Einstein, who’s first few papers merited the Nobel Prize. The only thing that should matter is whether the project significantly advances the field and whether it can be reasonably done. The rest is irrelevant. Science is in a way like the stock market: past results are not a guarantee of future gains. I have seen faculty who published a paper in Nature as a postdoc, then spent a lifetime surviving on 3rd rate papers. Also, productivity can be easily deformed by large labs. One of my previous bosses was the director of a research institute and had almost one thousand papers to his name because he was included on each paper produced by cca 45-50 scientists, in several very different fields, although he had only a vague idea of what was going on in each project. A beginning investigator, working all by themselves, can reasonably publish a paper every 1-2 years, even every 3 years if it is a really good paper that needs a lot of experimental evidence. In my opinion, the real progress comes from papers that are 3-4-5 years in the making and challenge existing concepts, not from papers that add a comma or an asterisk to existing knowledge. Sure, such research is useful too, but should receive much more limited resources.

While I agree that the references will give some idea about the applicant, I am strongly in favor of a double blind process, to eliminate any conflicts of interest. Too many times reviewers evaluate based on the name of the applicant, not on the merit of the application. Arguments like “I have many people in my lab and have to pay them” or “I am based in NY and have to pay my postdocs a living wage” are (or should be) irrelevant when evaluating an application. If they can’t support their post-docs because the application has low merit, then they need to reduce their personnel. Getting an NIH grant is not (should not) be a life-time entitlement, based on a “fame” acquired 10-20 years ago. Science is a very fluid field and large labs with two dozen postdocs have much less flexibility and dynamism than a lab with 2-3 people, and are in fact a barrier to research progress. 20 people in a lab will all look to the PI for guidance and inevitably all research ideas will have a limited scope and horizon, limited to the vision of one person- the PI. In contrast the same number of people split among 10 labs will generate 10 different ideas, providing more dynamism. Again arguments like “Having more resources concentrated in one place will generate a more focused and powerful advance” is also ridiculous, since small labs can easily pool resources or apply for an institutional grant for more expensive equipment. Even a double blind process is not a guarantee, since PIs with more clout will block ideas that contradict, or are more advanced than their own work, in order to keep open their access to grants. To mitigate that, I would suggest the review panel to include mostly researchers from overseas, from several other countries, who are outside of the local circles of interest, and do not care about reprisals from US reviewers. I am sure that for a large number of people the NIH could get travel discounts. In addition, foreign researchers do not compete for US grants and would be much more objective.

All these new policies from a respectable agency such as NIH (probably the most respected one) should be applied to another agencies such as NIJ.

What about implicit lobbying of reviewers by inviting them as “guest speakers”, all expenses paid? These invitations often come with substantial financial honorariums. There may be no explicit bribery in this practice, but it certainly creates a quid pro quo. Isn’t that a COI? Why aren’t reviewers who accept such invitations and financial gifts required to declare them when reviewing applications?

Because that would take a good deal of hard work and due diligence on part of SROs. They are not interested in making waves or seeking real COIs that reviewers don’t disclose. True soul-searching will tell you the peer review system is rife with abuses. There is tit for tat going on. Grudge matches are being played out. Favors are being doled out. You don’t have to violate the letter of the law that Michael and Sally allude to above to do do this. You don’t have to breach legality to be unethical.

Inviting an eminent colleague in your field to speak at your institution is not necessarily a political move, though. It could be a legitimate collegial thing to do, provided you don’t discuss the actual grant application during their visit.

Now, if you scan the study section roster and intentionally invite someone who will be a primary reviewer of your application, it would then be on that reviewer to recuse themselves from the process when the application is assigned to them. That would be detrimental to the applicant, as they would have less expert review of their application and possibly lose the influence of a reviewer who would otherwise have advocated for their funding.

A colleague of mine just got his R01 funded on a second trial. The first time it was not discussed. Without any revisions, he resubmitted as new, and invited as a guest speaker the primary reviewer. He learned about the identity of the primary reviewer from another member of the study section. The secondary reviewer happened to be interviewing for a job at our institution, and although he was not employed yet when the study section met, he was in the final stages of negotiations, which involved meetings with the applicant. What should I be doing at this point? Report all 3 reviewers and the applicant to NIH? Should I inform my institution about the PI’s conduct? Should I be concerned that if I do so, it might ruin 4 individuals’ careers? Should I be concerned that such allegations would bog down NIH in endless investigations and re-review of applications?

We absolutely do want to know about situations such as these! We do follow-up, making every effort to respond in a thoughtful and discrete manner, and we will do what is needed to assure the integrity and credibility of peer review. Please send the details to the NIH Review Policy Officer at ReviewPolicyOfficer@nih.gov.

Honest question – I am being made aware that e.g. a study section member shares his/her assigned grants with postdocs in the lab. who do I contact? The SRO? is there a formal process of reporting breaches? Honestly, from my little experience of serving on study sections, the problem of sharing confidential information with others is so pervasive that a major reset is necessary. this is especially critical for new PIs, who need to include novel/exciting data in their applications and thus need to have complete confidence in the process.

I totally agree. It does not reveal the process for the whistle blowers. And I have to agree that all of the four examples do happen all the time. Its very unfortunate.

My suggestion to make it clearer is to open the process of review. That is, just as the reviewer knows who the P.I is, why can’t the P.I know who the reviewer is. If we let this totally open, malpractices could be contained at the least. Bad reviewers will think twice to breach.

Great question, thank you! It’s really important that you and others in similar situations report the possible breach immediately so that we at the NIH can follow up in real time. It’s also important that you and others provide as much specific information as possible about the incident. Be assured that if we are equipped with timely and sufficient information, we will follow up (but may not be able to let you know the resolution). You should contact either the Scientific Review Officer who is managing the review of the application in question, or contact me, the NIH Review Policy Officer, at ReviewPolicyOfficer@nih.gov. Thanks again, Sally

What was not mentioned here concerns whether CSR will alert the P.I. if it is found that their NIH grant proposal has been circulated to people outside of the study section review panel. How do I know if my proposal’s ideas have been emailed to other countries, for example? Or possibly circulated to competing investigators in this country? I think I ought to have a right to know.

And another issue: what do you do when you see your ideas and even research stemming from an unfunded Specific Aim on a reviewers’ poster board at a conference? Breaches are widespread and a hard look at peer review needs to be undertaken.

I think the real problem is that the rosters of review panels are made public. As an applicant, I am almost certain which panelists review my proposals, and as a reviewer, too many times the applicant knows I reviewed their proposal. This is s situation where transparency works against peer review integrity.

I respectfully disagree. Reviewers’ names must be public. It’s a matter of transparency. Experts in the field of review may have conflicts of interest based on the potential for eliminating competition or simply because their research contradicts what is proposed in the reviewed applications, or because the application engages in non-mainstream research directions.

In contrast, the name of the applicants, which institutions they are in, what they have published before MUST NOT BE KNOWN by the reviewers so that applications are solely (primarily!) based on their scientific merit (novelty and significance).

I disagree – both from my perspective as a reviewer (while on a 2nd “tour of duty” as a regular member of CSR-chartered study section) and as an applicant. Each variant has imperfections, but in the medium and long run, confidence of active scientists themselves in the process is essential (the more we voice a lack of confidence, the more Congressional and public support [not least, $$$$] erode. It is crucial that applicants and the public be able to see who was doing those reviews by experts that can be claimed as the foundation of making the least bad possible decisions at a time when the problems of decent pay lines or success rates are the institutionalized crisis. [As a senior colleague pointed out, whose applications go to SEPs because he is doing service to NIH as a regular on the only study section in his area, seeing this capacity eliminated by CSR in the context of SEPs (to protect reviewers when the panel is small, and likely an A1 will be reviewed by a completely different pick-up team on the sand lot) is a good way to get a real sense of the value of knowing who is on the panel. To people posting concerns about scientific conflicts of interest that fall outside the scope of NIH COI definitions (which mostly are FCOI) – use the cover letter to communicate and explain serious scientific COI and I bet the SRO will make sure to avoid that member (another benefit of being able to see who is on the panel! Does not cover possible ad hoc reviewers, but one can even spell out those conflicts).

How is this very important policy enforceable?

When I was a postdoc decades ago, in two different labs, I was distressed that the PI breached confidentiality,

In each case, the powerful man who ran the lab, gave me a copy of an NIH grant that he had been assigned to review and asked me to check whether there were any ideas in the grant that might be helpful to our lab.

One commented, if I recall correctly, that the work was “too close” to ours, implying that he would give it a bad score,

Given power structures, how is a postdoc in a position to file a formal complaint that will have any impact? How will the postdoc be able to continue his or her research in that lab or to find another job after that?

The PI will of course deny the comment (it is not in writing) and say that the postdoc “misunderstood”.

As long as postdocs and graduate students remain, in effect, indentured servants, it is hard for them to stand up for the rights of others—-they barely are in a position to stand up for their own rights.

Spot on. Powerful people in entertainment, journalism, finance, and ACADEMIA are getting away with murder, while impotent watchdogs are too afraid to mete out justice.

I am sorry that happened, but I would have said no and reminded him that it was a serious breach. Sometimes you have to stand up for what is right.

I have been thinking about my comment and perhaps in an attempt to intimidate a PI from sharing the proposal, all proposals should have, on an important page, such as the same page as the research summary or plan, an all CAPS bold statement that the grant should not be seen by anyone other than (name of assigned reviewer) and that if someone else finds they have access to the grant they should contact (with assurances for complete confidentiality): give the name and contact info for the Scientific Review Officer

If anyone is trying to submit a comment using Internet Explorer and is not seeing their comment being published, our Captcha is not working in some versions of IE and so those comments are not coming through to us. Please do not take offense. If you would just switch to another browser to comment while we fix the issue, we would appreciate it.

What about addressing the simple yet fundamental issue of scientific quality? I have a whole collection of Alice in the Wonderland stories laboriously manufactured by study sections. The first place is currently held by the genius who claimed that peptides are not good candidates for viral attachment inhibitors (specifically – a gp120 modulator), because they have trouble crossing cell membranes; I have developed so low an opinion about the NIH-associated “scientific community” that I feel compelled to explain: viral attachment inhibitors act on EXTRAcellular targets. I never received any meaningful support from NIH staff in appealing the pseudoscience in summary statements.

There are repeated suggestions to make proposals anonymous or, conversely, to end anonymity of reviewers. Though well-intended it may be, it just is not going to work.

1. The anonymity of reviewers is a long-established principle which is there for a reason. Most people would never criticize openly another investigator if there is a chance the the roles might be reversed in the future. Or they would flatly refuse to review. In any scenario, this would lead to more, not less, distortions in the review outcomes.

2. Even if there is no “Investigator” review item (as is also sometimes suggested), it is still not realistic to assure the proposal anonymity. Every reviewer who knows his field can readily figure out where the proposal (or the manuscript) most probably comes from. We are just fooling ourselves pretending that we are doing bling reviews in some journals. It is especially so given that “Preliminary Data” are not only present, but are a crucial part of the grant proposal.

3. Besides, it doesn’t seem wise to totally exclude “Investigator” or “Environment” items from consideration. It is not very difficult to propose “pie in the sky” and to assemble a perfect research proposal if there is no need to justify that one has enough expertise/resources/collaborations to actually perform the research. Even now, I can see this happening often enough.

I am not proposing any remedies here, I am just pointing out that finding working solutions may be not as straightforward as it may seem to so many.

NSF doesn’t publish the names of panel members. But then, NSF isn’t known (at least at MCB) to be a great supporter of cutting edge studies. Much of their approach is to use the panel as a non-binding and superficial advisory board to the program managers. These program managers use their positions to distribute funds on the basis of an undisclosed metric. And this is rarely merit based. Hopefully, NIH will continue the way it is. This discussion seems to be over split hairs. Focus on how the overall NIH budget is distributed between direct costs and the extraordinarily high institutional overheads.

1. Not a problem, IMO. Instead of trashing bad applications and hurting egos, reviewers would be just scoring good applications higher. And some self-censorship is actually a good thing – the present practice of writing pseudoscientific nonsense under the cover of anonymity would be curbed (one hopes, at least).

3. Actually, my own reviewing experience involved a situation entirely opposite to a “pie in the sky”, i.e. a perfect approach combined with credentials/environment deficiencies (which, actually, should rather justify supporting the researcher!).

I saw an outstanding environment, stellar credentials, and properly mastered “grantsmanship”, combined with mediocre substance. I am afraid, this is what the current review paradigm at NIH promotes.

One reason for these infractions has been a lack of clarity about what happens to those who breach the rules. Even now, the offenders at M.D. Anderson were not disciplined per se and as far as I know we don’t even know what would have been suggested as a disciplinary action.

Someone revealing that they reviewed a particular application

Q: If they did how do you know? They talk over phone, do you check their phone records?

A reviewer disclosing how another reviewer scored an application

Q: They disclose over phone or in person, then, how do you catch them? They know you can’t that’s why they do it.

A principal investigator (PI) approaching a reviewer at a scientific conference to discuss her/his institution’s application in which s/he is designated as PI

Q: The main reason most PIs go to these conferences is to meet peers and lobby for their papers and grant applications. OK, they discussed in a conference, how do you know whether they did or not. Networking is unethical but everybody encourages you to network. Networking = lobbying.

All these policies just stay on paper, nobody follows them. Everybody knows it that’s why they keep on breaking these policies because they know you can’t catch them.

If the authorities responsible for peer review truly want integrity and fairness in the system, they have to model it after the justice system. Even though the justice system has many flaws, it got one thing right: separating those standing trial from those who are tasked with judging them. THERE IS NO WAY YOU CAN ACHIEVE FAIRNESS WHEN THE PEER REVIEWERS AND THE APPLICANTS KNOW EACH OTHER, ARE FREE TO MIX WITH EACH OTHER, ARE ALLOWED TO SWITCH ROLES, INVITE EACH OTHER AS GUESTS TO THEIR RESPECTIVE INSTITUTIONS, AND EVEN GIVE EACH OTHER MONETARY AND NON-MONETARY GIFTS (DISGUISED AS HONORARIA). Corruption (and the NIH is facing a form of corruption) is sure to ensue.

By posting reviewers information in the study section roasters, NIH’s original intent was transparency. However, by doing so NIH is unknowingly promoting this bad behavior. When you disclose who are the reviewers, these things happen…

1. PIs start inviting them as guest speakers to their institutions, make them friends and lobby for their applications.

2. Reviewers are scared to give bad scores to big famous PIs although the proposal is crappy because they are afraid that those PIs will take revenge. Because it is not that difficult to figure out who the reviewer is from that short list in the roaster.

3. Reviewers make other reviewers friends because they know their applications are reviewed by these guys and they form a big boys club and rub each others backs.

By publishing Reviewers names NIH is indirectly and unknowingly promoting bad behavior and corruption in the review process.

Is this really a big problem in NIH grant reviews? All the comments on impropriety appear to be anecdotal. It’ll be significant if actual incidents are brought up by naming names. From my occasional presence at a few grant panels, I’ve noticed that baring exceptions, there are three independent reviewers who score an application. This is followed by scoring by >20 other panel members. That’s a lot of people to ‘bribe’. The grants that are scored well are usually written well, by productive researchers. Those that don’t score well are usually the opposite. There may be exceptions, but it’s hard to pin them down. It’s likely, as in any system that there’s some nepotism. But again, it’s hard to identify and it’s unlikely that this plays a significant role in funding decisions.

I know several PIs whose budgets are more than 500 K direct per year and they routinely renewing their grants for the past 25 years. Some of them published only 2-3 original papers in mid level journals in a 5 year period as corresponding authors. Perhaps, it is always not true that these proposals are well written by very productive scientists.

Yes, more than >20 panel members score applications but the thing is they don’t even read the applications. Most of them have absolutely no idea what is written in the applications. They just score within the range based on 3 primary reviewers scores.

NIH has to come up with better solutions to make the system unbiased and fair to both senior and young scientists. They receive too many applications so the system is over loaded and broken. Reviewers have to review too many applications every cycle so they just write couple of talking points in the strengths and weakness and give scores 5-6. In that way, they don’t come for discussion so they don’t have to explain those scores.

Just restrict number of applications each PI submits per year, this will significantly improve the quality of the review process.

It is not about “bribes”, it is that one hand washes the other. You score well the grants I submit, and I will score well the applications that you submit. And they all usually attend the same conferences, hire each other’s post-docs, collaborate on papers, invite each other for presentations, and overall know each other quite well. It is an “old boys” system, composed of “well-established” investigators in a field, who have known each other for many years, where young investigators or newcomers from other fields are excluded from the start. I agree with “littlescientist” that NIH funding should not be a lifetime or career-long entitlement. Funding should be directly rewarding the merits of current application, and only of that. Funding should not reward past achievements, “personal fame”, the fame of the university, or a multitude of other criteria that have nothing to do with the application at hand. Current system essentially gives funding monopoly to a small group of researchers who dominate the field precisely because they have large funds and can afford to hire 15-20 people, which gives them an even larger number of papers and strengthens their monopoly even more. The only solution to break up this “old boys” system is to bring reviewers from overseas. The NIH officials must make sure of course that these reviewers are not former postdocs or collaborators of the applicants. Foreign reviewers would be much more objective and have no skin in the game since they are not competing for the funds to be distributed. This will also ensure that completely new ideas, often blocked by the “old boys” if they are competing with their own outdated models or projects, will have a better chance of receiving the funding they deserve. I think this is the only way to avoid a system where the wolf takes care of the sheep, which is an obvious conflict of interest. Of course, such ideas will be rejected by “well established” “experts” in the field because it threatens their livelihood. And that is precisely the point. An effective grant system should threaten the status-quo, because that guarantees real competition. I don’t care how many people some PIs have in their lab. What should matter is the advancement proposed by each application. If some PIs fall behind with ideas, they should close their labs or reduce their size. The problem is that current system does not allow that to occur. I have rarely seen a PI in rank of Associate Professor or Professor closing their labs, although many do mediocre work.

We are working to remind participants in the peer review process that we are all responsible for maintaining and upholding the integrity of peer review, including reporting violations to the NIH in a timely manner. In many cases, reports of integrity breaches come to us from individuals who have been approached or who have received inappropriate information. This is why we are working to heighten awareness of what constitutes inappropriate behavior. Remember that reviewers serve in NIH peer review at the discretion of the NIH so an immediate response is often to terminate a reviewer’s service in peer review. In the coming months we will be presenting case studies to demonstrate additional actions that the NIH is taking in response to reports of problematic behavior in peer review.

Double blind is easy to implement, with reviewers scoring approach and significance, and NIH judging the PI – eliminate productivity as criteria: otherwise anyone who has had a lapse in funding will never get funded again! That’s self-defeating from the scientific perspective and it’s one of the obstacles facing mid-career scientists, who happen to be the most disadvantaged in this system!

Fully agree with Nora’s comments! The productivity comment is particularly appropriate. Lapse of funding leads to lower productivity (!) concentrate funding in the hands of those who are funded, and “the rich get richer”! Being rich and richer is fine with me (after all, we are in the business of science!) but the consequence on scientific “biodiversity” are significant and adverse. Concentrating funding in the hands of a few decreases the number of novel ideas and limits research to the fields explored by the “rich” few!! I remember too well the advice of a seasonned researcher several years ago:” don’t try to push your own ideas, join a team that is funded and work on their ideas”!

The most common problem of the peer review process is breaches of peer review integrity. This occurs when an individual or company that is not a reliable source for material submitted to a journal, or an individual who submits fraudulent material, tries to have material assessed by the editors before it is published. These breaches of peer review can undermine the credibility of the entire peer review process and can even result in a loss of articles to journals. It is important for journals to have high quality standards so that they can attract reputable and knowledgeable peer review editors. If this peer review process is breached, then it can cause the reputation of the entire peer review system to be tainted, and articles that have been submitted to the Journal may not be accepted for publication.