6 Comments

NIH is the largest public funder of clinical trials in the United States. As stewards of this research enterprise, we have been actively listening and discussing how to overcome hurdles and shortcomings that we, and others in the research community, have identified. If you’ve been following the conversation, you’ll know that NIH already has implemented some key reforms to enhance clinical trial stewardship. Today, in a Viewpoint Essay published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), we provide an overview of how these reforms, and new initiatives, fit in to the broader picture of building a better clinical trial enterprise through better stewardship, accountability, and transparency.

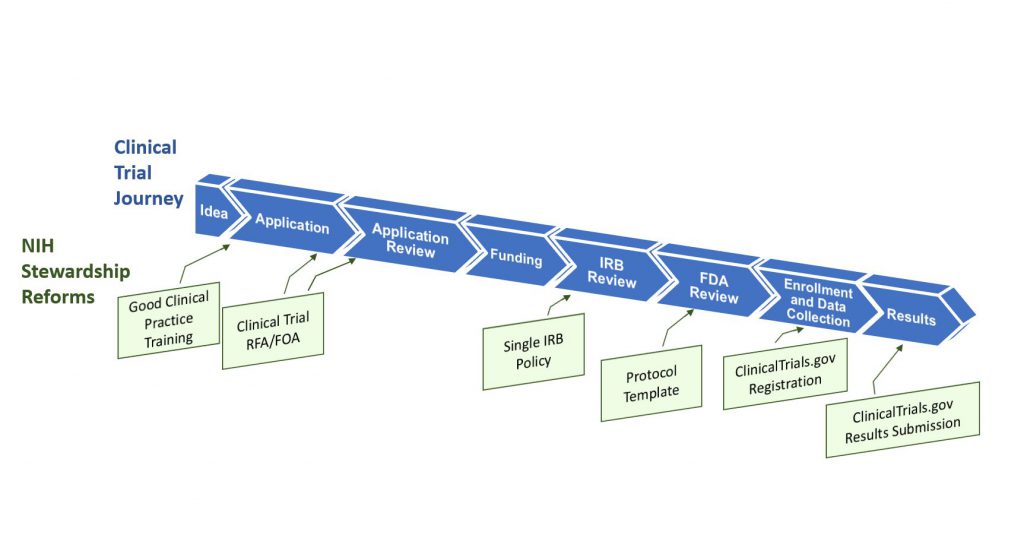

Figure 1 illustrates the clinical trial “lifespan”, and key opportunities for improving the quality and efficiency of clinical trials – opportunities that translate into more innovative and robust clinical trial design, and accelerated discoveries that will advance human health. NIH is leading a multi-faceted effort that addresses shortcomings and challenges throughout this lifespan, including the application and award process; the scientific review of trial applications; post-award management and oversight; sharing of trial data; and dissemination of research results information to the public.

Some key highlights from our essay:

- Good clinical practice training. New NIH policies issued today establish Good Clinical Practice (GCP) training expectations – effective January 1, 2017 — for investigators involved in NIH-supported trials, as well as for NIH staff who design, oversee, manage, or conduct clinical trials. There are many providers of GCP training, and institutions have the flexibility to choose the training program that is the best fit with their existing programs (some universities already include GCP in their institutional training requirements, for example).

- Changes to clinical trial applications. A new NIH policy issued today requires that the research community submit grant applications requesting support for clinical trials in response to clinical trial-specific funding opportunity announcements (FOAs). This policy is targeted to apply to applications submitted for due dates on or after September 27, 2017. This change will allow NIH to readily identify proposed clinical trials, to ensure that key pieces of trial-specific information are submitted with each application, and to ensure that trial-specific review criteria are uniformly applied. To give NIH institutes and centers flexibility across their different scientific areas, each NIH IC will be developing clinical trial FOAs that address their research funding priorities and strategic goals. There will be commonalities across FOAs, in that all clinical trial applications will need to contain key clinical trial-specific elements, such as protocol information. This change will mean that you will no longer be able to submit an application requesting support for a clinical trial on one of our parent announcements. You will need to identify an FOA that clearly invites clinical trial applications. We will publish reminders in the NIH Guide and NIH Extramural Nexus. Read today’s NIH Guide Notice for more information.

- Enhancing clinical trial registration and summary results information. A new HHS regulation released today specifies requirements for clinical trial registration and summary results information reporting. NIH also issued a policy today that complements the federal regulation and sets the same reporting expectations for all NIH-funded clinical trials whether or not they are subject to the regulation (to include, for example, phase 1 studies of FDA regulated products as well as studies of interventions not regulated by FDA, e.g., behavioral interventions.) Read more in a New England Journal of Medicine paper authored by NIH staff, and we’ve also written more about this change in a separate blog post published today.

- Use of a single institutional review board for multi-site studies. This NIH policy, issued in June 2016, will streamline and expedite institutional review board (IRB) review of clinical trials conducted across multiple sites. The policy establishes the expectation that a single IRB will be used for multi-site research as of May 25, 2017. (Read an earlier Open Mike post describing this change.)

- Clinical trial protocol template. To expedite both NIH and federal regulatory oversight processes, NIH, in collaboration with FDA, is developing a clinical trial protocol template for phase 2 and 3 Investigational New Drug (IND)/Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) clinical trials. NIH plans to encourage its use as a way to organize and standardize key details that should be included in clinical trial protocols. NIH is reviewing public comments and working toward an updated version of the template this fall and plans to develop an electronic clinical trial protocol template thereafter.

We encourage you to read our JAMA article, and the articles linked from this blog, for more information. We will continue to harmonize the establishment, conduct, and follow-through of clinical trials research in the upcoming months and years. As described in the JAMA article, clinical trials have evolved and improved over time, resulting in impressive advances, but there are still challenges that we must address. The suite of complementary activities described here intends to help fulfill our mission of improving health through scientific discovery, while preserving the public trust in research through efficient and transparent clinical trials.

Dear Mike,

What specific approach to Networks might be coming?

or will these be handled by ICs in different ways?

Hello – We expect that current operations will continue as is for clinical trial networks that are working well and that already meet the standards NIH will call for in its future clinical trial-specific funding opportunity announcements (FOAs).

I want to first convey my full support for the intent of the new NIH policies governing Phase II Clinical Trials, which is “that supported [NIH] trials investigate…questions…that have the highest likelihood to advance knowledge and improve health. (Hudson et al., JAMA)”

My major concern with the proposed new Phase II Clinical Trial guidelines is that they appear to focus exclusively on basic/medical science trials (drugs, devices, medical treatments) and to ignore behavioral interventions.

This raises very real issues regarding whether the new guidelines will bias the review process and subsequent funding of behavioral-focused interventions.

The new policies issued by NIH and the recent JAMA editorial suggest that my concerns regarding these issues are not unfounded.

For example, peer review of Phase II Clinical Trials will now take place in special study sections (personal communication with an NHLBI Scientific/Research Contact) rather than standing study sections. The composition of the panels is described in the recent JAMA article as:

“Peer review of NIH clinical trial applications must be conducted by study sections with appropriate expertise, such as clinical trialists, biostatisticians, and pharmacologists, as well as the basic science experts needed to evaluate the scientific rigor of relevant preclinical data provided.”

Further, information in this article indicates a “clinical trial template” (see: http://osp.od.nih.gov/sites/default/files/Protocol_Template_05Feb2016_508.pdf) which asks for a large amount of information that is completely unrelated to public health behavioral-focused interventions.

For instance, “titration” and “dose taper”, “study agents”, issues regarding “medications”, etc…

While certainly some of the information is relevant, the entire document is really focused on aspects specific to basic clinical/medical studies.

This is further emphasized in the new training requirement (see: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-16-148.html) on Good Clinical Practices which, at least from the CITI training website is designed for those researching investigative drugs, medical devices, and biologics.

Perhaps the most important aspect of these changes, which is never clearly stated in any of the recent information (either from Open Mike or the JAMA article) is the increased number of pages, types of information, and overall application burden required of those seeking to conduct a Phase II Clinical Trial.

It is very important that investigators familiarize themselves with the additional required documents for these types of applications (see: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-16-405.html)

In addition to the standard 12 page Research Strategy, the new documents require up to an additional 29 pages of information.

Overall, the new requirements indicate that the NIH’s strong medical model focus has dominated the process of developing the new clinical trials guidelines and will require scientists conducting public health and behavioral interventions in community, school and other non-medical settings to attempt to shove a square peg (behavioral interventions) into a round hole (trials of drugs, devices or medical treatments). Behavioral interventions conducted in community settings certainly present a number of challenges, but they are not the challenges on which the new guidelines seem to focus.

Unless safeguards are established, clearly articulated and monitored, it seems likely that behavioral scientists will be jumping through a number of additional hoops (many of them irrelevant) in order to submit intervention applications, while being placed at a distinct disadvantage in a review process that seems focused on the medical model at the expense of public health approaches to achieving NIH’s goal of enhancing health, lengthening life, and reducing illness and disability.

I have been wondering about this too. The new policies, program announcements, and review procedures seem very much geared to studies that are truly clinical in nature. Behavioral interventions in non-clinical settings (e.g., community-based obesity prevention or school-based physical activity interventions) really don’t fit the new model and requirements, but meet the definition of a “clinical trial” and presumably will be required to comply.

Also, the requirements for new documents (at least as described in the new NHLBI clinical trials program announcement) are very burdensome, but most of the NHLBI-funded scientists I have talked to don’t seem to be aware of them.

I would like to pitch in a few other points of concern that go beyond even how technically well clinical trials are run or reported and that is as follows:

1) What steps are being taken to make sure the “Not Invented Here” joke so prevalent outside the US is not true- ie no matter what trials are done very well in Canada, Europe, Australia, New Zealand etc and have clear outcomes, are still run again her at huge expense to draw the exact same conclusion – and so drain NIH funds without increasing knowledge.

2) What steps are being taken to ensure that when NIH has built a clinical infrastucture (network etc) to undertake clinical trials (MFM network, OPRU network etc) that NIH then allow NIH investigators with valid questions to ask using those resources by applying direct to an NIH study section (not the network) for an R03, 21 or 01 to get connected based on independent review, and not as a decision of the network.

3) Given the large amount of money being spent on the Human placenta project to study normal placenta – essentially creating 5 USA based MRI imaging centers much like a clinical network, when will there be proper follow up to allow basic and clinical follow up on common diseases of pregnancy? These could be in much the same way- R01 applications to make use of those teams while they are in place.

Hi,

I am Rajeev Bhushan former clinical research professional at AIIMS, New Delhi. I have worked with a multicentric Phase-3 clinical trial in multiple therapeutic areas.

Transparency and safety are the must in any clinical trial.There are many guidelines and regulatory body have such as GCP, HIPPA, IRB, and USAFDA taking care of the clinical trial. Before to start any trial, proper certification and training are required. Qualified Investigator and associate are playing a major role to do the transparent clinical trial. Internal and independent auditing is required.Public awareness is a must.