139 Comments

We recently received a letter from a group of extramural scientists expressing concerns about the sunsetting of the A2 applications. I thought that the entire NIH research community would be interested in reading our response….

Many thanks to you and your colleagues for your letter describing concerns about the policy sunsetting the A2 resubmission applications, and for your input on the partial or total restoration of A2 applications. The large number of signatories on the letter demonstrates the depth of concern on this issue. As you know, we at NIH have given the issue of the length of time it takes to fund meritorious science considerable thought. The policy to sunset A2 applications was developed with substantial deliberation and has been in place for over two years. It was published in the Federal Register on October 8, 2008, with implementation beginning on January 25, 2009, as part of NIH efforts to Enhance Peer Review.

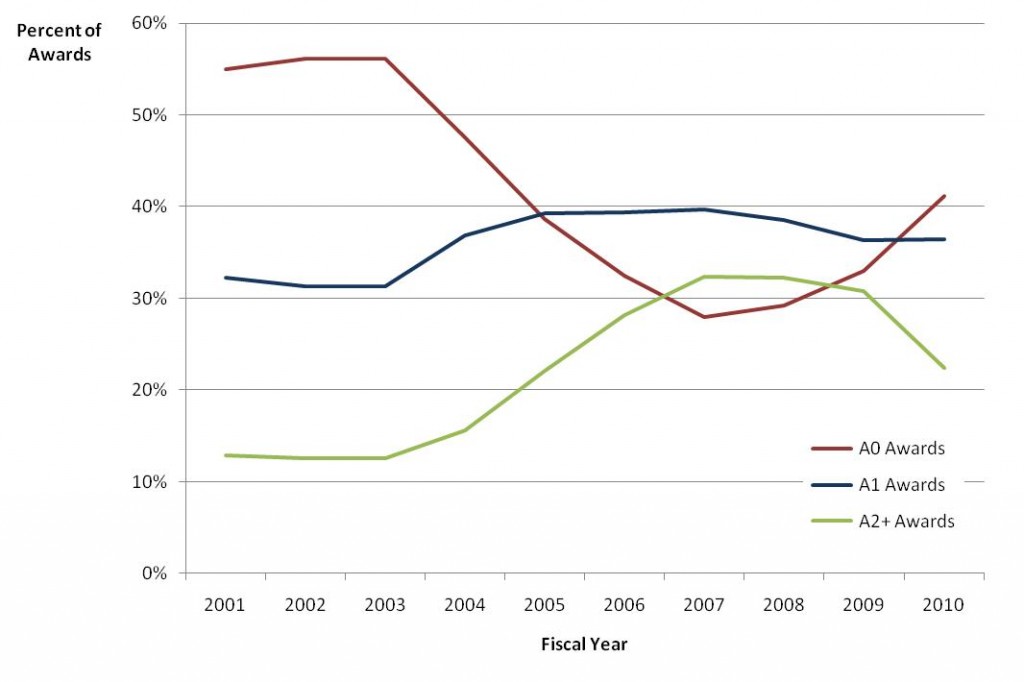

One of the concerns expressed at the time the policy was being developed was that applications were piling up as A1s and A2s in a “queue” awaiting funding. Data were collected showing that grants funded on their first submission (A0) had dropped significantly during the previous five years (See the Feb. 2008 NIH Peer Review Self-Study page 33). Furthermore, virtually all applications that initially scored in the top 20% were eventually funded but only after “waiting” one or two years in the A1/A2 queue. The overwhelming recommendation was to find a way to fund the same number of applications containing the most meritorious science earlier. Various strategies were discussed, and after additional input and analysis, Dr. Elias Zerhouni, then Director of NIH, decided to sunset A2 applications.

Is the policy working? It certainly has achieved the intended goals: the number of applications funded as A0s is increasing and there is no queue piling up at the A1 level (Fig. 1). In other words, the proportion of funded A1 applications has remained constant while the proportion of funded A0s has risen dramatically. In the near future more grants will be funded as A0s and over time, this should translate into a decreasing likelihood of highly meritorious applications needing even one resubmission.

Figure 1: Distribution of each year’s new R01 awards by version

There is little doubt that some great science is not being funded because pay lines are decreasing, regardless of the number of permitted resubmissions. Restoring A2 applications will not change that picture and will increase the time and effort required for writing additional resubmissions.

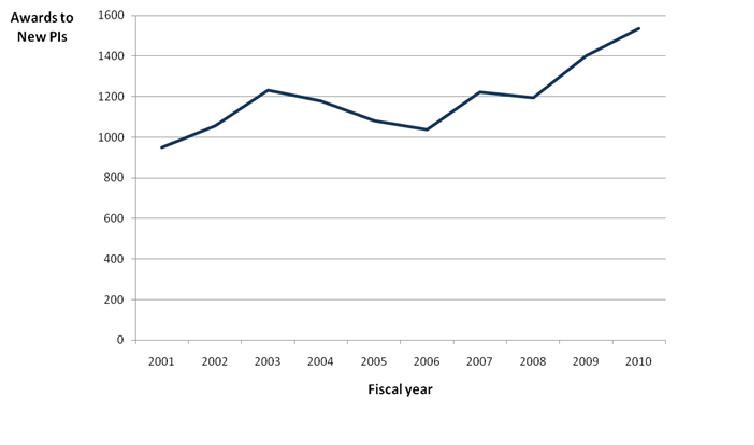

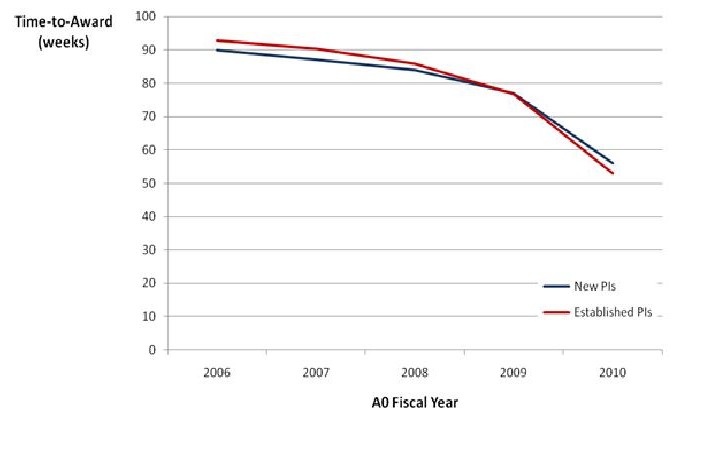

The new A2 policy also appears to not have had a negative effect on new or early career investigators. As shown in figures 2 and 3, the new and early career investigators are doing relatively well, thanks also to NIH guidance to Institutes to fund similar percentages of R01 applications submitted from new and established investigators. Even with the new resubmission policy, the percentage of R01 funded applications from new investigators has increased to the present 30% of total competing R01 applications. Reinstating the A2 policy could particularly affect new and early career investigators who are now experiencing a shorter time to award (Fig. 3), thus allowing them to conduct independent research earlier in their careers.

Figure 2. Awards of new, unsolicited R01 grants to new NIH investigators.

Figure 3. Investigators’ time-to-award. New, unsolicited R01 applications, by fiscal year of original A0 application.

Another concern in your letter was the uncertainty in the scientific community about what constitutes a new application versus an extensively modified application. The policy is the same as the one that we have had since 1997 the only difference is previously, the policy applied to A3s and now it applies to A2s. But we agree with you that the determination about what constitutes a new application is not always easy and some applications are in “gray areas.” To enhance fairness, consistency, and transparency, we have instituted a formal appeal process which allows the applicant to provide a rationale for reconsidering the decision.

In addition, it is important to note that each Institute and Center uses scientific priority setting to inform their funding decisions and invest funds strategically to best meet their mission. In some cases, this means that applications are selected for funding that fall outside of the payline while others that fall within the payline may not be selected for funding. This flexibility allows NIH to fund highly meritorious and programmatically relevant A0 and A1 applications even if they fall outside the payline. Therefore, it is unlikely that permitting the review of additional revised applications will substantially change the science that NIH supports.

Thank you again for sharing your thoughts. We will continue to evaluate the outcomes of this and other peer review policies and have planned to include the issue of sunsetting the A2 application in the next round of peer review enhancement surveys. We will continue to adjust our policies to adapt to scientific progress and changes in fiscal realities.

Sincerely,

Sally J. Rockey, Ph.D.

Deputy Director for Extramural ResearchLawrence A. Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Principal Deputy Director

Nice to see that the NIH will ignore the opinions of thousands of scientists, mostly study section members, who think this is a bad policy.

I agree entirely – it’s a disgrace.

And the “supporting data” are an even greater insult as they use numbers from years in which the budget was reasonable and A2 applications were in the >25%-ile, to support the policy now, when grants are not funded at 6%-ile. Surely, scientists at the NIH understand that the “support” is tendentious at best.

Hank, considering it’s this group of study section members who got us in this mess, I say let’s ignore them as much as possible.

The response ignores the fact that potentially high-impact proposals are now lost forever as a consequence of the very low payline. While in good times the verdict of reviewers usually is acceptible, in times like this it is not at all unlikely that an A1 proposal that goes unfunded is still highly meritorious. My feeling is that when the score is high unfunded applications should have the opportunity to come back. As it is now, the investigator is forced to change the entire proposal in another one or at least try to give the NIH the idea that it is another one. Why is that necessary? If an application goes unscored twice, I can accept that. But when it gets scores of 2.0 and 1.8 and remains unfunded it should have the opportunity to come back at least one more time.

Jan Vijg

The response ignores some anecdotes in favor of a quantitative analysis. And you scientists have a problem with that?

Thank you Dr. Rockey, these are fascinating data. I find it interesting that the trend reversal in A0 awards started in 2008, and maybe even 2007, before full implementation of the policy. That suggests even discussing the elimination of the A2 perhaps affected study section behavior. It seems clear that the policy is working, especially encouraging that it did not burden new investigators. Shorter time to funding, under similar success rates, is a win for everyone.

The statistics demonstrating a shorter time to funding are biased. Or at least the conclusions. This is because the analysis excludes the events for those outstanding-science applications (of which both sides agree are being lost) that are lost forever. If they fail at A1 then they are eliminated as a data point when in fact they would clearly show that the time to success for meritorious grants has increased. I wonder what other types of statistical mockery the NIH administration has employed? For instance, is the increased percentage of first time success skewed due to the loss of A2 success events? As for the larger question, is better science being funded? Of course not. So if this is a paternal effort on the part of non-scientist administration to make us feel like the process is fair, then it has failed. The system is now officially more arbitrary and less fair than before. Nice Job!!

This response to our petition is INSULTING. This new policy takes outstanding proposals – that just miss the exceedingly slim payline – and prohibits scientists from submitting them again. This is done to make reviewing easier, not distribute limited funds in a more effective way.

If you really care about supporting the greatest number of scientists, and help young ones develop, you would limit the number of awards to all labs, e.g. one government grant per lab. NOT tell labs that they can no longer submit their best ideas.

Carcinogenesis prof. How many different projects does a lab have to have in order to get funded. Usually a lab focuses on one or two major project from one or two R01’s. If a non fundable score is reached at the A1 stage the project is dead. What does the young scientist do since that is the person that probably has only one major project that they work on. How can that person come up with new preliminary data to resubmit the A1 such that it is substantially different? Very few grants will be funded when pay line is 6 percentile. The peer review system is currently broken and those few that are getting funded on the first or second submission probably know people on the study section who are helping them.

@MC: I completely agree. This process is broken, there are technologies being funded through grants that have no chance ever of being accepted and largely being fueled by the fact of older PIs support. The whole process is frustrating and completely SUBJECTIVE at this point. The review process should be a combination of peer review, young scientist, and industry participation, with more weight given to merit of proposal and not the publication history of PIs.

I agree with this 100%, in that an A2 submission is required to catch the payline that missed funding by one point. It is very very unfortunate.

It is also unacceptable that a study section memebr holds more than 3-4 R01 grants in one lab, while an established investigator looses the renewal of the only one R01 grant, due lack of an oppurtunity to address the key concerns via A2 submission.

I agree. There should be a cap on the number and funding of RO1s for one PI. I do not think one PI could write proposals to get millions of dollars every year and meanwhile train or mentor more than 10 PhDs and 10 graduate students. It is not a good idea for one PI to spend several millions of dollars a year. At least, as a taxpayer, I do not want to spend my money in that way. There should be a cap for the maximum amount of any RO1.

To have a fair review system, it may need a place that anyone (including panel members) can provide feedbacks anonymously of any reviewers; bad reviewers should be eliminated from the review system for ever; some reviewers are really bad!!!!

I would also like to point out that those of us that agree to work as study section members do so at great disadvantage. If you think your grant review is bad at a standing study section then you should try going to the SEPs that are arbitrarily thrown together to review grants of study section members. In addition, I can vouch for the fact that the idea to eliminate A2s did not arise from reviewers complaining about resubmission. I personally found the resubmission process very useful for young and established investigators alike, much more than a simple queuing.

Hank Seifert: Did you even read this ? It shows with DATA why the new system is working. And opinions of thousands of scientists is just that – just opinions based on personal biases. Where is the meat or data in your gripe ? The fact of the matter is that there is not enough money to fund all meritorious applications. Being denied by a few percentile points on your A2 is no different than being denied on your A1.

Hank – it sounds like you didn’t even read our petition. I looked at the data, and as a reply to the petition, I find it insulting. Of course the number of original and once-amended applications that are funded will go up because it’s a zero-sum situation. Eliminate A1’s and the number of original applications funded will go up to 100%, and the time to funding will be minimal. This isn’t data, it’s a misuse of statistics.

Being denied on an A2 **IS** quite different than on an A1 if there are new criticisms of the A1 that must be answered. Now, if there was a rule that no NEW criticisms could be levied at an A1, that might be different, but it may also simply stifle the reasons for a poor score. With shorter applications, I am finding more criticisms of proposals to the effect that “The PI didn’t mention | consider | cite | include …”. If these criticisms are the grounds for denial, and space is so limited, then there should be an opportunity to respond to new criticisms.

The killer is actually not the restriction to one amended application, but the disallowing of any future similar proposals. As others have clearly said on this thread, and was stated in the petition, small labs and new investigators are being disproportionately hurt by these rules, and eliminating A2 applications only makes it worse.

Damn the data provided by NIH! The NIH is not even collecting data on the labs that have gone dark, the ideas that have been orphaned, or the new and potentially new investigators that have been discouraged by the current funding situation, and the new rules that make the current funding situation even worse.

This should have been addressed to NInv, not to Hank – sorry.

Yeah, damn the data provided by the NIH. I just need the money. Nuff said I guess

Another comment on the validity of their so-called data – some institutes (NHLBI for one) are now funding A0 applications at a higher payline than A1s, which will clearly skew the data. Lying with statistics is rampant here.

I was on study section for years, until this past summer, when I finally rotated off – our ‘behavior’ didn’t change because of the A2 ‘sunset’. It didn’t change at all. The pool of grants changed – perhaps applicants gave up, but fewer A2s were crossing our plates. And the increase in A2s being funded coincided with decreased funding, not a change in review.

The problem is not scientists – it is low funding levels.

The attitude that reviewers and applicants alike must be somehow whipped into shape is insulting and confrontational. We as scientists should all stop agreeing to review for CSR while they continue to institute policies that are so heavy-handed, mis-guided, and anti-investigator.

NInv,

By your logic, why allow even one re-submission? Here’s a thought: remove the stratification of scoring on A1s. Make the vote binary, up or down, fund or no fund. I’m a bit tired of the riduculous notion that study sections “don’t/can’t/shouldn’t make funding decisions in these times of no $. EVERYONE knows that voting a 3 is voting to not fund, whereas voting 1 or 2 is voting to fund. So, go ahead and stratify for A0’s but vote up or down on A1s.

My second beef, and this one is huge, concerns what constitutes a “new, fresh approach”. Some of the anecdotal comments regarding the advice given by PO’s would be hilarious if they weren’t in fact so tragic like “Switch to calcium channels”. You might as well advise someone to enter into prostitution. The official advice given in the NIH FAQ is worse! There it says things like, “Switch from mice to yeast” AND “Switch transcription factors” as examples of required change. Are you kidding me? Again you might as well tell a banker to switch to bank robbing: its a total prostitution of our scientific values, integrity and intellectual honesty. And we wonder why the best students aren’t going to grad school!

All I can think about is how my A2 was funded with a 7% score but my A1 with a 13% score wasn’t. Without that funding my lab would have shut down.

Here here. I had an A2 funded at 2% the A1 was 16% and not funded. In addition one of the reviewers on the A1 had no clue what the grant was about. The other two reviews were very positive but not enough to bring it down to funding level which I believe was 15% at the time.

The timing of the data they are showing is suspect so I am not even sure if it is relevant to the issue at hand.

I would like to see data on how mid level investigators are faring in the new system now that young less experienced investigators are getting special treatment and their less meritorious grants are being funded. I am talking about people too young to retire but too old to do anything else. We had a new investigator get a grant funded at 26% while my last 10% score was not funded. Funding wasn’t great when I started either but we didn’t get any special breaks.

Dr. Rockey, I think you are missing a very important point of the A2 discussion. The concern over the A2 issue is driven by the current funding climate that has created an “abnormal” situation. In normally flush funding times I think most everyone would agree that the A2 could be eliminated. However, in the current funding crisis, many highly rated grants from long-established leaders in their fields are ending up just outside the paylines, which are now less than 10%. Grants scoring 10, 11, 12% are not getting funded. These scores indicate the grant is meritorius, but has simply not made an extreme payline. In cases like this, it does not seem right that such investigators have to completely change their lines of investigation, because this is not at the root of the problem, the root is the payline. These grants deserve another hearing at the study section because there is often there is a ‘circle the airport’ mentality about scoring, even though this is never articulated outright. I am sure that the study section’s intention is not to force the investigator to entirely change their research focus.

I think a reasonable alternative is to re-establish the A2 for some period of time until the payline becomes reasonable, because in better times the borderline grants would be funded and those that dont make the payline are more likely to be poor grants that really do need a change of focus. This temporary restoration of the A2 could be at the discretion of the director. I strongly encourage you to consider this alternative.

thank you for your consideration.

I agree with this.

No matter what the pay line is, the reviewer bias is a major problem in this limited funding times in that expected funding for A2 applications with publications and concerns addressed with relevant new preliminary data is not even looked at is unfourtunate, so we have close the lab??? cannot continue to training the new or old students any more. Very frustrating.

Very nicely put, and a logical suggestion.

You have ignored the major point of the letter. We who serve on study sections cannot differentiate between the grants that are making the funding cutoff and the A1 grant which are now deemed to be not worth further condideation. Good science is being demised by people who do not have to compete for funding. Please let peer review happen.

I would like a study of the near miss A1s. I would particularly like to know the fate of near miss A1s, submitted by junior investigators. How does it affect their science and their careers? Thanks,

The fundamental issue, obviously, is lack of sufficient funds to fund meritorious research. Perhaps it’s finally time to wean institutions from the overhead that saps research funding and keeps paylines so low. If overhead were set at 25% across the board, take-it-or leave-it, this might shake up things in a positive direction.

This point is huge – it astounds me that some institutes are allowed to ask for 90%. For every one grant these institutes get, a lab at a smaller institute shuts down. This is disgraceful.

Well said! The institutions rich enough to invest in their research infrastructure have and are reaping the dividends in the form of mega-grant awards. They do not need the obscene indirects at the expense of 7 percentile funding rates.

The response states several times that NIH funds “meritorious science” and “meritorious applications”. NIH should not use “meritorious” anymore, because it DOES NOT SUPPORT “meritorious science” – NIH supports based on other principles, including who do you know in the study section and the Institute. No matter what data NIH can make, the agency managed to destroy the scientific progress and the good science in this country. Please no longer use “meritorious” when you elaborate on who does NIH fund.

I agree with this 100%, and I am glad that some one speaks this loud on this.

The study sections members are very much looking at the applicant’s name and the institute; most recently there is a trend in that the members choose the grants from geopgraphical location of the institute.

“Meritorius” grants at NIH is not true any more.

I did not sign the letter but I wish that I had done so because I do not think sunsetting A2s was a wise decision, especially given that the timing coincided with a major change in grant structure. I think the new policy will result in a greater influence of luck and politics in the system.

I am a senior investigator and I recently had a proposal (A1) killed (42nd percentile) but 2 out 3 reviewers had not reviewed the previous version and raised different concerns – the 1 reviewer that had reviewed both the A0 and A1 gave scores of 1 to 2 – I feel unlucky. If I had another shot I am confident I could address the new concerns.

The data presented in the NIH response are interesting and leave me wondering 2 things. First, the proportion of funding of A0, A1, and A2s seemed appropriate in the early 2000s. What caused the drift across time and couldn’t this be addressed rather than eliminating A2s? Second, there seemed to be a reverse trend even before sunsetting A2s leaving me to believe that it was not necessary to make such a drastic change.

I agree with this completely. The NIH systems make us to beleive in luck and politics and not science. Some of the investigators like me completed the R01 grant with publications very successfully, but cannot be successful in the renewal even after A2, because I did not understand the key element of luck and ploitics in the review system, I relaized existence of that that route very late, and the NIH review system is not fixing that problem. My era common site is full with applications not discussed.

Am I the only one that thinks the increasing percentage of funded A0’s is self-evident and simply a matter of mathematics than a change in intrinsic performance? If you take away the percentage of grants funded at A2, that percentage has to go somewhere.

So really, that graph showing the increase in A0 is classic correlation without any proof of causation. Had this type of thinking been submitted as an R01 proposal, it would have been triaged.

You are correct – and that is the point of the policy. The hope is to fund more of the pipeline of good ideas the first time, to avoid the delays inherent in resubmissions. Queuing new submissions in order to fund in A2 wastes time and delays progress. By the time you go through A2, the idea is at least 18 months old – stale in many fields. Eliminating A2 also forces reviewers to decide to support applications in order of real merit rather than deferring with an intermediate score and encouragement to clean up minor details that don’t really change the science.

Yes, this change comes at a substantial cost to those who were caught in the middle, but that should be temporary. The changes in NIH policy are intended to to make the best of a very poor situation. Whether these changes help or not, we are absolutely losing good science to weak budget support.

Sorry, but this is just not logical. A2s are almost always substantially different from Aos, and hardly stale, just by being A2s – they have undergone substantial revision. You could just as easily make the argument that ‘Fresh’ ideas in A0 applications are by definition not well enough developed, and should require a round of review and revision before funding. Either statement would be specious.

I’m sorry Dr. Hamilton but your answer is not meaningful. So you’re saying that eliminating A2s will fund more A0, and you accept that this premise is mostly just a shift in numbers. But I thought the point of the review process was to reward good science, not just change the category of *when* a project is funded.

There is an implicit fallacy in this line of thought (and in the new system itself), which is that A0s present better science than A1s and A2s. We know this is implicitly true because why else would the agency try to shift to fund more A0s? Because they’re bad science?

Of course not. Therefore, the reverse is true that the agency implicitly believes in an inherent superiority of A0s. And *that* is the piece of datum missing behind this whole new shift: what proof does the NIH have that shifting the approval percentage to A0s will improve the science?

And I have to say that I find this sentence from a scientist shocking: “By the time you go through A2, the idea is at least 18 months old – stale in many fields.”

Projects continue and take a life of their own depending on how the data come out. Your comment suggests that everything is static and stuck in time for 18 months. What do you think people amend A0s with? New. Data.

I’m sorry but I’m simply left shaking my head at what you’ve typed as a response*.

* Also note that I agree with Dr. Manley’s response below.

It is interesting to note that a R01 grant that I was awarded as a ‘new investigator’ in 2001 is listed like an A0 in the NIH RePorter , but it was definitely an A2. I believe it was correctly listed as an A2 in Nov. 2010. If the NIH RePorter is the common source of the data for Fig. 1, it would mean that funding of A2’s in 2001 was higher than reported in Fig. 1. Also, I would have expected a higher proportion of A2 funding during 2001-2007, than is shown in Fig. 1. If this represents a larger systematic error in the data base, piling up may not be a recent phenomenon. It may have been occurring to a similar extent much earlier.

The issue that is ignored here is that the new regulation favor a certain type of science. If you have to write a new application, you will have to provide new set of preliminary data. W/o preliminary data there will be no funding. If you test a bunch of chemicals or hormones on cell lines to “cure cancer” it is easy to take another cell line and test the same agents. If you new cell line is from a different species – voila, you got a new grant application. If you work to understand physiological approaches in whole animal systems, it is very difficult to generate several independent sets of preliminary data. Thus, the loss of A2 applications is a major loss of a whole set of data, often a loss of many years of building a model system.

Do we really want to abandon organismal approaches at at time when it becomes clear that context is so very important for the action of all interventional medicine?

Even though the data shows there is no negative effect of this policy on new PI. The fact that new PI often cannot get funded (esp. with RO1) after their initial start up package runs out. In general, new PI have only one technician to start with and need more time to collect preliminary data and can not afford large complicated experiments.

Would it be possible to restore A2 for new investigator?

Thanks

I completely agree. My A1 score actually went down because the study section reviewers were primarily ad hoc compared to the first review panel. Thus, they completely ignored my revisions and came up with their own wish lists. Having an A2 would at least have given me a fair chance to address these. Now, I have submitted a “new” grant that is essentially a re-packaged old grant because I only have a single large project ongoing in my lab as a new investigator. The A1 sunsetting policy hurts new investigators. Now I am spending start up funds that will end in a year in an attempt to tide me over.

A serious issue that prevents fair implementation of this policy is that the reviewers for the A1 application are often not the same as the reviewers for the original A0 application. Because of this deficiency of the system, even though the grant applicants satisfactorily addressed issues raised by the reviewers for the A0 application, the scores often become worse for many applicants because the A1 reviewers may not share the same concerns as the A0 reviewers and raise new issues that could be very different from (sometimes opposite to) those in the first set of reviews.

I strongly suggest all funding agencies, including NIH, to model peer review system of journal articles, which has been working very well for many years. In the journal article review system, the same set of reviewers review both the original and revised submissions, unless there are conflicting views from the reviewers. Journal editors judge the quality of both submissions and reviewers’ comments, and allow rebuttal of unfair reviews or reviews that missed a major point or fact. It is a try-and-work system and we should try to model it.

I agree with this. Keep the same reveiwers or same concerns shared by the reveiwers to merit the effort of the investigator to get their grant funding possibilites via A1 or A2 is OK with this.

I was originally in strong favor of eliminating A2, but I have changed my mind. What it has done is to cut short the scientific discussion through which a junior PI could defend a highly novel idea, challenge any incorrect peer reviews and dismantle popular beliefs. The effects are particularly severe when the PI is working in an unusual field and is not from a well-known lab that everyone trusts already. Reviewers need time to adapt to a novel idea outside their area of expertise.

The problem is that the NIH cycle was shortened by shortening the discussion rather than shortening the ‘dead’ time between discussions. Personally, I think that the reviews have gotten worse, more out of line. The preliminary scores are all over the place, from almost all straight 1 to as low as 8 for the same application.

I was wondering, how do you measure “meritorious”?

It would have been nice if Rockey had published the petition, so I could read the arguments she is rebutting. I’m left feeling I’m hearing half a phone conversation.

But the data is persuasive, and my personal experience backs it up. Dumping the A2s mean you write one less proposal and wait a year or more less to get about the same money you would have got.

NIH and reviewers don’t particularly like to talk about the amount of noise in review scores, but the fact is that it is substantial. It probably gets worse towards the low end, which means as money tightens, the process becomes more arbitrary. This is not to criticize. NIH does a pretty good job of controlling the noise in the review process, and I don’t have a handy suggestion for an alternative process that would work better.

But this is the real issue. When there is enough money to fund most of the research that most of the community thinks is worth funding, then the review process works very well. When money is so tight that even very promising ideas can’t be pursued, then minor flaws in the review process become major problems.

But none of this is actually related to dropping the A2s. The petitioners note a large number of meritorious A1s that don’t get funded. According to the data, if you add back in A2s, the number of unfunded meritorious A0s and A1s stays almost exactly the same, and all you do is delay. It’s pretty mathematically obvious why this is the most likely and nearly inevitable outcome.

Erik – agreed that the fundamental problem is not related to dropping the A2s. The problems are (a) a shortage of money compared to the number of scientists we have trained and established, and (b) the prohibition against resubmitting substantially the same idea (i.e. not only are A2s prohibited, but you can’t resubmit the proposal that you, with your career of expertise in an area, think is your best proposal).

I want to test X in system Y because it promises to reveal the pathogenic mechanism of disease Z. Even the study section reviewers agree, and that’s why they gave it an 11 %tile score! The only ‘weakness’ mentioned was an entirely new issue raised in review of the A1, that is easily answered. Yet, I am now forever prohibited from resubmitting this idea under the current rules. This is an asinine way to distribute scarce funds.

Dropping the A2s is not the real issue – I agree – but it is the wrong response to the current situation, and only makes it worse. Let me resubmit as an A0 and I won’t complain about dropping the A2s. I’ve got a proposal that 7 reviewers have ranked in the 11-15 %tile, and the only criticism of the A1 version is easily answered. What sense is there in forcing my lab to SHUT DOWN without any option to respond to a new and obviously minor criticism?

In tough times, it is vitally important to keep as many labs as possible operating. This can only be done by limiting the amount of direct money going to each lab, and the amount of indirect money going to each institution. It cannot be done with policies that only keep the fat labs fed.

Drs. Rockey and Tabak, you wrote:

I don’t see how one can enhance the transparency of a process with zero transparency by instituting an appeal process that has zero transparency. Would you please explain where you perceive any transparency at all in the current system?

Wouldn’t a process with transparency:

1) tell the applicant the specific reasons for rejection; and

2) tell the applicant which of the three review phases described on the CSR web site had been completed?

Neuroman – the only thing transparent in this process is that NIH is trying to make their job easier. They can’t measure fairness, so they aren’t rewarded for fairness. They are measured, ruled, and rewarded by politically influential scientists with large labs and multiple grants, who have a vested interest in the status quo because it puts them at the top of the pile, and secures their funding no matter how few grants are funded.

The large majority of colleagues and study section members I talked to would prefer reinstatement of A2s.

Dr. Rockey would be hard pressed to find as many RO1-funded scientists support her position as did the Benezra petition.

Dear Dr. Rockey:

Elimination of A2 should be reconsidered for several reasons:

1. Over repeated reviews by standing study sections, the feasibility of each project can be most reliably judged by ongoing productivity of the applicant towards reaching some or all of the specific aims

2. The A2 should be reinstated for grants reaching a certain threshold upon A1 review, minimum between 9 to 33 percentile

Thank you for your consideration…

I think discontinuing the A2 applications is a great policy and I’m fully in favor of keeping it. It means that less time is spent chasing money and more time can be spent actually doing science. I appreciate being able to know whether an application is likely to be funded more quickly. Getting rid of the A2 submission, in which many good applications were being needlessly nitpicked, allows me to submit more grant applications, make better and faster decisions about which to pursue and which to abandon, and to publish more. This is all positive and allows me to concentrate more on moving science forward than on going back and forth with review committees over minutiae.

It is good to reinstate the A2 applications. At the same time the review members should respect the A2 application. In some cases, there is a mind preset on not to discuss the A2 application because it was not scored in the previos cycle.

I wonder how you can do science without money and how you can write more grants without preliminary data.

This is ideal if you have a lot of people working for you in the lab and can quickly generate data to switch to other projects.

But for most young/new PI, there is only one technician and one or two projects. They just cannot switch that easily and being denied of A2 will make many of them out of job!!! They are the ones with little kids at home to be fed!!!

Thanks

The problem with both the petition and the NIH response is that the two sides have very different concerns.

NIH is concerned with funding as much science as possible that will make a “big splash” that can be presented to congress to justify the budget in addition to forwarding the NIH mission.

The investigators in the community would love to accomplish that but are also concerned with their careers. The reason that the loss of A2s is much more of a consequence to individual scientific careers than anyone expected is that it is accompanied by a new computer program that makes decisions on overlap with prior applications. Thus, new applications on anything resembling the prior grant topic are not getting through now (the “appeal” process is a joke, one member of my department changed a grant nearly 80% but the molecule studied was the same and the appeal was denied) while five years ago, as a study section member I saw what I would consider “A3s” submitted as A0s, on a regular basis, many who got funded.

The loss of the A2s has already shuttered two labs of senior investigators in my department since this draconian enforcement means that investigators who have a A1 grant just missing the payline need a new, completely unrelated topic to resubmit on. Since they are no longer eligible for startup packages to generate new preliminary data on such projects, they really have little hope of ever being funded again.

I have to say I was shocked to see that 30% of new R01s are for new investigators. If this is sustained, it means that no one in the future can expect more than 2 or 3 funded grants in their career total. since that only leaves 70% of the grant pie for folks who are trying to sustain a scientific career over 20 or 30 years (which would need at minimum 5 funded grants to accomplish)

One thing that I would like to mention in regard to the pressure on pay lines. I dont actually think the problem so much is multiple grants held by an investigator, it is that R01 budgets have inflated mightily in the past few years if my study section has been representative. I seldom get “modular” grants to review these days and budgets in the 400k+ range are the norm. I currently hold two, modular R01s whose total amount of funding is less than all of the single R01s I reviewed in the last round. NIH should not be paying 150K plus in investigator salaries with 80k+ technicians. You might say that reviewers need to step up to stop this. However, NIH does not let us. If the investigator is on soft money we are told by NIH that this amount is what this investigator needs to do the work and we should mark the budget as “appropriate”.

I agree with the comments regarding the onus of developing new preliminary data, as well as those mentioning the time required to challenge dogma, but in general the new policy seems logical to me. And it seems to be working. I’m not sure that we’ll ever return to the glory days where funding levels are more reasonable. As such, I support a policy designed to put money into PIs’ hands more quickly, with less time spent chasing a grant that won’t make it. The harsh reality is that there’s some good science that will never be funded. Having an A2 round won’t solve that problem, and instead just delays the inevitable.

I find merit in elements of both arguments. From the NIH’s standpoint, A2s are indeed a problem, burdening peer review and helping create a very problematic queue effect. However, inadequacies in peer review result in many A1s being left unfunded, unfairly, without recourse for resubmission. Something is required to fix this, as the current situation is inadequate. Meritorious science in a just-miss A1 should not be required to be significantly revamped. The “appeal process” is not transparent, and from what I have seen, inexpert and Draconian. One solution is that A1s that are close yet miss should be made eligible for administrative review (which is not perfunctory) , after clear milestones for a resubmission are spelled out by peer review. Also, NIH needs to rethink their definition of new science in a grant and work more closely with scientists to help them reformalute studies; there are few scientists these days, either young or established, that can abandon costly ideas and preliminary data for the sake of creating something sufficiently “new.”

The removal of the A2 only works if funding levels are able to fund all meritorious grants. The A2 is an important intrinsic safeguard for meritocracy funding. I have seen way too many highly meritorious grants not funded in the study section that I sit on, and this includes many A1s that received scoring in the top 20 percentile. Unfortunately, these are simply numbers and chosen statistics to the NIH and Dr. Rockey. To those whose careers are destroyed by this insensitivity this is a life changing event that has an enormous impact on the livelihood of professional scientists that have dedicated their future to the betterment of health in the United States.

What is clearly needed and what NIH is so reticent about changing are measures that generate additional sources of revenue within NIH for funding meritorious R01 grants. I can’t say that I agree with everything in the much discussed February D. Noonan post at this site (http://nexus.od.nih.gov/all/2011/01/31/future-biomedical-workforce/), but I have to agree with many of the “Priorities” this investigator suggested for freeing up money for funding meritorious grants. I also must state that anyone willing to use their real name in this blog site is either a fool or a true believer in the principles they ascribe to. Hopefully it is the latter for D. Noonan. At any rate, if NIH believes that these cost cutting measures that they have implemented for the sake of saving money and time are worth the careers they are sacrificing, then they deserve the ignominy they are destined for.

The A0/A1/A2 data in Figure 1 is misleading. A0 funding is going up because the A2 is going away. The only choices for funding are A0 or A1. Naturally those two go up over time.

I am very happy to be retiring before having to submit any renewals as it is clear the folks who developed and defend removing A2s do not understand statistics. How do you increase funded A0s when the percentiles are less than 10? Where is the graph showing the numbers of new RO1s being submitted? Good luck to everyone else when the Congress guts the NIH budget – another advantage for Chinese science and economy to pull ahead of the US even faster.

I expect to see labs in Beijing and Shanghai filled with postdocs from the US in the next few years. I can see the PIs in the department trying to figure out how to say and remember difficult names like Matthews.

Wow, Bob, just…. wow. What an offensive thing to say. In so many ways.

I have no problem with A2 applications being eliminated. In fact, I advocate elimination of all A1 applications as well. Everyone gets one shot at glory. If you are denied, rework your application and submit as a new application. No more A1/A2 mess. We are right now producing far too many Ph.D. students as is. Most will not make it as independent investigators. If you lose your grant, tough luck. Try to get a K award.

Also, how many of you have complained about the “old boys/girls” club in study sections? Abolish all standing study sections. Convene them as special emphasis 1 year sections to review applications.

I am sick of US universities turning into European bastions where the “big guys” get all the funding and the little people are designated to working under them for the rest of their lives.

1) payline crashes

2) grant format is radically altered (25 pages to 12)

3) scoring system is radically altered (50 point scale reduced to 9 points)

3) A2 grants are eliminated

4) major emphasis on disallowing failed grant topics from being resubmitted

Once #1 happened, why did the NIH even consider, simultaneously, making all these other major, untested changes?

It’s sad but clearly true: CSR knows what is good for us, and only their opinion matters.

I was one of the investigators who signed the petition. I have to say that I was very disappointed by the very superficial and poorly argued response that we received from the NIH. Clearly, there are major issues with the policy, which eliminated A2 revisions – our argument was presented at the petition and I don’t want to repeat it here. However, elimination of A2 revisions is not the only problem with the new “enhanced” peer review system.

The new peer review system clearly has some good features. These include 9-point scale, scoring of individual criteria, structured applications and comments, as well as funding of new investigators on the same level as senior investigators. However, the new system also has a number of serious flaws, which make the entire review process flawed.

1) Shorter proposal format essentially eliminated the background section. Some background information still can be added in the Approach section, but the space is so limited that only a very small amount of highly pertinent information can be squeezed in. The idea behind this policy was that an expert reviewer must have sufficient knowledge of the field, and s/he would not need to read a literature review to conduct a professional evaluation of a proposal. This would make sense if the reviewers were indeed experts, but in most cases they are not. This would also work if the reviewers were willing to spend time and learn about the topic of the proposal, but in most cases they don’t. The reality also is that the increasing number investigators work in the areas, which are not covered by regular study sections, but their grants are reviewed by the regular study sections anyway – ad hoc reviewers are rarely invited. This results in a very superficial unprofessional and biased review process. This would not be, perhaps, such a big deal if the number of resubmissions would not be limited to just one – one would hope that somewhere along the way the proposal would be reviewed by the experts and receive a fair evaluation; however, the elimination of A2s made that very unlikely. My recent personal experience with the new peer review system was horrific. My R01 went through two rounds of peer review by two different study sections in 2010. I was absolutely stunned by how ignorant reviewers were. I could get more professional comments from people on the street. If the background section was still there, it could be used to educate these “reviewers” about the field and, perhaps, spare me the burden and frustration of reading ignorant comments. But the real issue here is not the background section or elimination of A2 revisions. The real issue is inability or unwillingness of the CSR staff to do their job, which is to ensure expert and fair review of NIH proposals. Just last week, I had the pleasure of finally reaching my SRA after several e-mails and voice mails (and several weeks waiting for him to call me back) just to hear from him that he cannot invite expert reviewers for every grant, which is reviewed by that study section. But what about expert and fair review proclaimed in the CSR’s mission statement?!

2) Scores for individual criteria seemed like a good idea, but what is the point in assigning scores for those criteria if the final impact score has absolutely nothing to do with these individual scores?! It appears that the NIH is not quite consistent here. If you introduced individual scores, why don’t you calculate the impact score as the average of individual scores? Apparently, the NIH staff recently realized that they have a problem with the impact score and introduced the summary paragraph, but this had absolutely no effect on how the impact score is assigned.

3) Bulleted comments also seemed like a good idea, but in reality it boiled down to often meaningless and dry statements, which have little value for the applicant.

My overall impression is that the new “enhanced” peer review system was engineered by the senior investigators/administrators/reviewers to make THEIR life easier and reduce administrative burden. Shorter applications and bulleted comments were clearly introduced at the request of senior investigators/reviewers, and had extremely negative impact on the quality of the review process. The shorter application format and non-expert reviewers do not go well together. It made the review process more unpredictable, less professional and more biased. For me as a new investigator, who received an R21 grant under the old system and had recent experience with the new system, the old system was overall much better than the new one primarily because of the background section, detailed comments and A2s – the A2s were especially important for new investigators who are usually not very experienced in writing grants. The old system favored quality over speed, while the new system favors speed over quality. The unresponsive and unprofessional CSR staff has been a real disappointment. If the NIH really wants to improve the quality of the peer review system and make it fairer, they should pay more attention to the quality of reviewers, reorganize study sections to more accurately reflect current fields of study, reintroduce the background section, i.e., lengthen the application, rethink how the impact score is calculated and make it transparent, and finally return the A2 revision at least for the new investigators. It is nice that the NIH will address these issues in its next survey of extramural grantees late this year. Hopefully, there will be enough of us left to conduct the survey.

My colleagues make excellent points! I feel that part of the reason for eliminating A2 is to relieve some of the burden on the review process. However, as someone who has served on more study sections then I would like to count, I would rather review a few more grants then see A2s eliminated. This is especially true with the shorter grant format in which the projects are described in broad terms without hard-core technical details. Personally, I gain much insight into the PI and project by reading the responses to previous reviews. Additionally, A2s are usually very clean and enjoyable to read.

I’m confused. Does this mean that my recently reviewed A2 at about 20% definitely will not be funded? Yes or no?

I think the comment by BIOINIL should be given serious thought by the NIH. I have also mentioned on several occassions (and on different blogs) that with the new A2 sunset policy it is time that NIH change the review policy for grants. The same reviewers should evaluate the A1 grant if the NIH is interested in keeping the labs operational in which they have already invested substantial funds in the past. Otherwise there will be a lack of “senior” investigators to guide the new ones to be successful in their careers.

I think NIH has realized that they cannot keep all those labs operational.

But Buds, the senior investigators who are able to adapt to and keep ahead of the current situation are the ones who will be sticking around, and, frankly, are the ones we WANT here to guide us–not the ones who just crank and moan and blame their worries on us.

It seems to me that there are two variables in the past few years that could influence funding lines for new investigators. First we have had an aggressive policy in favor of funding new investigators by lowering the bar drastically for those who have not had funding before. Second we have had this removal of communication between reviewers and applicants, by shortening reviews and reducing ability to resubmit. Is it possible that the positive effect of the first was cancelled out by a negative effect of the second?

I think NIH needs to allow resubmission of A2 if the A1 application score above 25 percentile or if the A1 reviewers think it could be substantially improved by the recommended revisions.

Scientist will always attempt to submit applications on their best science supported by previous work and area of expertise. Huge amounts of resources will be wasted on this idea of computers and NIH staff judging if an application is sufficiently “different” to be allowed scientific review (and scientists trying to make fake differences that can beat the computers). It will make academic science an even more randomly unfair and frustrating experience. Will anybody ever again be able in good conscience to suggest an academic science career to young people trained in their lab?

Actually, it’s really not expensive or time consuming to run a document through a similarity checker. It takes a few minutes for NIH proposal-sized documents, and the readouts make it extremely straightforward to judge whether contiguous sections are the same or whether there has been sufficient reshuffling. Most universities now have these programs available to their faculty for checking student work, and it would be extremely easy for PIs to self-check their re-vamped proposals to see if they were likely to pass the difference muster.

Yep, they did this with my qualifying exam (~10 pages of grantwriting) in less than 5 minutes. Is this really going to cause the NIH to come to a halt? Nope, just more of little boys crying wolf.

I think the current NIH policy on grant submissions is misguided and wrong. NIH should never engage in thought-policing by cross-checking a grant application against earlier applications by the same PI. This is a dangerous step away from peer review. It should be resisted.

A grant application should be accepted regardless of how often it has been submitted before, once, twice, or x times. Many PIs are familiar with the following situation. A grant is submitted and receives a score that is not fundable, and remains unfundable after an A1 or A2 re-submission. The same grant, further revised or not, is then submitted at a later time, perhaps to a different study section, and receives a fundable score. The grant may have improved over time, the subject matter of the application may initially not have been recognized as significant but now is, or the grant has now been reviewed by a different set of reviewers who find the science simply much more attractive. Whatever the reason, it would be a shame to eliminate such applications prior to review. Good research projects (or, in NIH language, excellent, outstanding, or exceptional projects) often take time.

NIH is clearly fighting the wrong battle here. Instead of thought-policing investigators, NIH should focus its efforts on improving paylines. There are several straightforward options. Limit the max number of concurrently active R01 grants per PI to two. Cap F&A costs at 50-60%. Eliminate programs that were not investigator-initiated and have generated sub-par bang-for-the-buck. Do not accept grants in which the applicant institution commits to less than 50% of the PI salary. These are simple measures that would direct more of US taxpayer dollars to good and productive science. We all hope that NIH will now begin to address the real issues.

I couldn’t agree more.

The problem at NIH is allocation (miss-allocation??) of funds. Period.

The current system is not working….unless the NIH preferred outcome is to drive all independent researchers under the umbrella of mega-programs overseen by overworked, over-hyped and over-funded UberProfs who are often conflicted with ties to venture capital/biotech/pharma.

Requiring applicants with meritorious grants (8-20%) to reinvent/disguise their project so that it can “qualify” to be reviewed is simply not acceptable. It is intellectually dishonest and it is counterproductive. If we assume that investigators submit the strongest application possible, it follows that the “new” application will be weaker. We are being asked to commit professional suicide.

If we all drop out of the system, NIH’s “data” on the funding of meritorious ROl applications will only get better.

If there are currently about twice as many RO1-dependent faculty positions as there is money at NIH, then that number needs to get smaller. In other words, half the people currently getting in the 10% to 20% ranking on the A1 need to switch to situations where they are funded from somewhere else. The way the new system is set up, individuals learn that they are not going to be NIH-funded when their A1 proposal doesn’t quite make the cut. If NIH kept the A2, the message would simply come at a different place. Keeping A2s would not change the fact that at least half the investigators, most highly meritorious, will take a substantially different career path than what they had planned.

In total agreement with Ivan Gerling……….a computer at NIH recently decided that my new grant was an A3 when the body of the grant was considerably altered without much alteration in the specific aims! How much direction can one change? Unfortunately NIH was non-responsive when it came to me pointing out to them the differences. Appeal process is a hoax in my opinion.

The great villain in the drama of NIH funding in the past decade is the poor level of funding afforded by our elected representatives (of all parties). On that background, NIH administrators have done their best to shuffle the deck chairs of our Titanic research effort. They have changed the scoring system (a waste of time, IMHO), shortened the applications/critiques (jury still out, IMHO), and they have eliminated the A2 (neither here nor there, IMHO).

The only problem in this is, as Dr. Rockey states, is with the policy on resubmission following a terminally rejected proposal has stood unchanged since the days of A3 applications. Clearly, there are a many scientifically valid proposals which cannot be funded. To demand that investigators successfully deceive the NIH into believing that their retooled grant is really “sufficiently new” is something of an insult to all involved. At a time when all admit that good ideas must go unfunded, we need a more clear-eyed way for retooled and improved ideas to get fair consideration without having to deceive. Patching an outdated and harmful policy with a formal review board is not sufficient in my mind.

Under the old system, applicants could argue with misguided critiques of A0 and they did not have to cave in until and unless A1 received the same criticisms. A2 critiques tended to reflect what happens when applicants have to swallow the bitter pill of going along with critiques with which they disagree.

Under the new system, applicants are more reluctant to argue with A0 critiques because they only have one more chance. This comes at a time of growing concerns (reflected in a number of the previous comments) about the uneven quality of critiques and about applications being assigned to reviewers who lack relevant expertise.

Consequently, in some cases, applicants find themselves in the difficult position of having to go along with misguided critiques. Sometimes the applicants themselves are wrong or misguided — but sometimes the applicants are right, and they know more about the best way to conduct the research in question than do any of the reviewers.

This is not a great way to foster meritorious science. There is still room for improvement of the peer review system.

To quote Upton Sinclair: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

I remember well in the early- to mid-90’s, when there was another drop in funding levels because of NIH budget cuts, that graphs and statistics came from the NIH explaining just the opposite: how funding levels were actually getting better and how, for example, new investigators (R29s then) were getting funded at record levels, i.e., at the 28th percentile where some Institute’s R01s were as low as 10th percentile. Of course, much of this was based on the fallacious use of statistics. Indeed, many publications in the late 90s showed that the “more efficient” funding of new investigators was due to manupulation of the important statistical issues: over 60% of the young investigators had left the system, the 28th percentile was not a per-grant number (as with R01s) but a per-investigator number, and new investigators needed to average two re-submissions in order to get funded (vs. one for established investigators’ R01s). In other words, the NIH left out the most important data need to assess whether the system was working as intended.

The same is happening here. Cogent, well-justified arguments put forward by the Benezra petition ( I signed it) are met with statistics showing that NIH is doing a great job rather than taking into consideration the motivations for the petition. Simply put, the current graphs offered are difficult to interpret given the scant data and associated definitions. For example, is the recent increase in A0 funding affected by the one-time wave of ARRA grants (which would all be Aos)? Since Study Section members are admonished NOT to discuss grants in the context of “funding” (the infamous F-word), how is it that there are more A0 grants being funded? It must be at the Administrative level. However, the petition is not addressing the top X% funded by this mechanism, it is addressing the next group of outstanding grants with levels of merit that are really impossible to parse, especially given the heterogeneity of reviews, reviewers and other intangibles. Re-introducing the use of the A2 mechanism under appropriate (not universal) conditions would go far to address these deficiences.

In the same way, it is fallacious to present a graph showing decreased time required to funding a grant as evidence of “system improvement”. Of course, it takes less time if a grant is funded by its A1 than if it had to be funded in its A2! However, who among us would not invest the extra 6-9 months if it made the difference between no funding versus 5 years of funding.

The NIH extramural funding mechanism, with all its own merits, suffers from specific, and in some case chronic deficiencies. Those of us involved in a large part in the writing and reviewing of these grants are in a position to give important advice on how to improve the system in order to get the best science and scientists funded.

To quote Upton Sinclair: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

Ummm, dude you could use that quote right on back at all the investigators from the other direction of this argument.

Word, Arlenna.

I’ve said it many times but it bears constant repeating. Anyone with a dog in this hunt- line up your top five problems with the NIH grant process and list your top five solutions. How many of the former point the finger at you or your lab? How many of the latter disadvantage your career or your lab?

Why do I suspect from reading these comments that the modal honest answer is “none. And none.”?

Another famous quotation is in order here

“Do it to Julia! Not me, Julia!”

It is interesting how easily is NIH discounting the opinion of more than 3,000 NIH-funded investigators. Everybody knows that when pay lines fall lower than the 10th percentile, then the peer-review system breaks down. It will tend to fund the strongest laboratories that have multiple NIH grants and other resources, while the individual R01-funded investigator will be overlooked. Serious consideration should be given to maximize the number of PIs funded by the R01 mechanism. This may necessitate substantial reduction in center grants that divert funds to other activities (translational, etc), as well as reducing the intramural program and the number of grants awarded to individual investigators. There is a crisis in the NIH peer-review system that needs to be addressed.

You do realise that there are more than 30,000 investigators actively funded by the NIH. So a vocal 10% who clearly has personal benefit in the old system is ignored. Suck it up.

Do you realize that not everyone got a chance to sign the petition? For instance I never saw it, and I am sure neither did many other researchers. So the numbers don’t mean just 10 % of scientists agree with the petition.

I was just saying that saying 3000 investigators signed it when not saying that over 10 times that number is funded by the NIH is misleading. And as long as only 3000 signed, it means just that, by simple math.

DR. ROCKEY, Hope you are reading these post! Overwhelming negative reaction to the NIH response.

I don’t agree with the comments being made towards the study section members. The need to reduce the time burden seemed reasonable in my opinion and generally the feedback I have had on grants recently has been interpretable.

However, I think the practice of bringing new reviewers in to judge A1 applications in light of the A2 being discontinued needs to be scrutinized more. Like many of us, I have a personal example of an R01 just missing the mark (13th %) due largely to a reviewer bring up an entirely new list of concerns while the other two had clearly read the grant before. I can think of a few suggestions to fix this:

1) Reviewers need to commit to the life of the grants they review. A study section member who expresses their desire to step off should not receive new grants and only be responsible for the A1s related to their reviewing. As a result, stepping down might take a year or two but with reduced work load on each round.

2) New reviewers for A1s should not be allowed to score outside of the range. This could be based on the A0 reviews or on the reviews of the continuous reviewers.

3) New reviewers should indicate when they are raising new concerns on an A1 application and this would then open that grant to an A2 application.

One cannot argue that the time to fund grants has decreased. But the obvious debate here is whether this metric provides the best means for advancing American Science. On this point, it strikes me that an important issue is being overlooked.

During the roughly two years that it took to fund an A2 application, investigators invested much effort in honing and improving their best science. This commonly involved creative “financial leveraging” in which promising (and ultimately funded) projects were temporarily supported through private funding, no cost extensions (in the case of renewals), and even University “Bridge Grants”. Since so many A2s were ultimately funded, the time and money involved was well spent for several reasons. First, outside funding from many sources helped keep the most meritorious projects viable, a benefit that seems to be unappreciated. Second and perhaps more importantly, this outside funding could be viewed as “subsidizing” NIH projects during the long renewal process. Third, every grant waiting to be funded, freed up dollars to fund other grants in the interim. In essence, the A2 policy allowed 5-6 years of research viability to be maintained for every 3-5 years of funding. Even though some labs temporarily operated on shoestring budgets and progress was slowed, the policy provided a means to stretch NIH dollars and keep some of the very best (top 10-20%) programs alive. This is critical to sustain the long-term investment in US scientific “intellectual property” during periods of tight funding. The final irony here is that many Universities were, to varying degrees, willing to subsidize projects with the prospect of future funding. They are exceedingly unlikely to do so for projects deemed non-viable under the current system. Given that current funding levels make it nearly impossible to truly distinguish and support the best scientific proposals, benefits of the A2 application must be carefully weighed against weaknesses.

I hope that these consequences can be entered into the current debate.

The major problem, and the reason for so much anger and anxiety, is that investigators who have had an unsuccessful A1 are being told that they cannot submit another proposal on that topic unless it is radically altered. This is the case even if it barely missed the payline and they have generated new data that make the proposal much stronger.

A simple solution is to allow investigators, at their own discretion, to revise a previous grant and submit it as a new grant or to incorporate sections of a previous grant into a new grant without regard to how similar it is to the earlier proposal. The A2 can simply be treated as a new A0 without a prior review history and receive a new review by the same or a different study section depending on how it is assigned. This would not unduly burden study sections.

There is no need for the NIH to decide when an investigator must abandon a given line of research, nor is it necessary for the NIH to examine a grant application for similarities to a previous application. And if the NIH does not reject applications based on similarities to old applications, then there is also no need to put an appeals process in place. Simply let individual investigators decide what to include in their applications and let the review committees rank those applications based on their merits.

Incidentally, I noticed that Mario Capecchi had an A2 application funded in 1995, which was sufficiently productive to be renewed as an R37 award in 2004, three years before he received his Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. So sometimes an application that has been revised more than one time might still be deserving of consideration.

Bravo and well said! There is a valid argument for not having resubmissions at all, but allowing an investigator to resubmit new applications at will. Reviewers are told that we do not have to consider the score from the prior review anyway if issues not found in the prior review are apparent in a resubmission. Thus, it seems logical to not have resubmissions but also not to police what folks submit as a first submission.

Resubmissions allow investigator to improve the application in response to criticism. Especially new investigator that might not be as good in expressing ideas vs. experienced investigator. But I think that the major issue is not in limiting the proposal to one resubmission, but with the fact that after one resubmission the investigator has to submit a substantially different application. Is that really going to improve science? It appears to me this policy will less affect large well established laboratories with many different projects going. In such an established laboratory, an investigator can quickly shift focus and collect preliminary data for a new proposal. It is much harder to come up with a substantially different application from a small laboratory with limited resources.

As many above have stated, one of the major problems with the review process is the presence of new reviewers for an A1. I strongly agree with the post suggesting a step-down process for members of a study section that are leaving. Additionally, reviewers should not be allowed to bring up new problems. If the reviewer did not spend enough time on the grant in the first round, they should not suddenly be able to “find” a new reason to score a grant poorly. This means that the investigator can work hard, solve the problems, improve the science and INCREASE their chance of having a proposal funded. Isn’t this purpose?

and the real problem is……..drum roll…………lack of money

A compromise articulated in the petition that is worth emphasizing is the idea that there could/should be a “score limit” on any new A2 applications. In other words, most of our concern is about A1’s that received strong scores and are obviously meritorious, but which were not funded due to the extremely low paylines. A reasonable limit would be a 20-25% percentile, which would be considered for funding in good times, but is well out of range now.

I’ve been reading the comments to date with much interest – I too signed the petition – and only partially tongue-in-cheek propose a solution: there is obviously more good science being proposed than there is money to fund it. In addition to the obvious need for reductions in indirects percentages and increases in institutional commitment to PIs with respect to the percentage of salary, why not gather up all of the proposals that “should” be funded, and hold a lottery. At the very least, it might reduce the need for study section reviewers to search for reasons to not score a particular grant. In addition, it would bring out into the open the “luck” aspect of the process. So, you’d get a decent score on your grant, and then be entered into the lottery. Another suggestion – de-identify the applications for an initial review by study section members, pick the ones which score well for the science alone, and then discuss those – re-identified – for the final study section meeting. I agree with those who believe the system is broken – the NIH is going to have to start thinking outside their own little box to solve this problem. As for me – I’m probably going to have to find another career, or find an “Uber-PI” with whom to work.

As at least some of the commenters here have recognized, the number of grants that can be funded each fiscal year is zero-sum (leaving aside for this purpose the issue of grant size). Thus, the *only* possible thing that can be coherently argued as a problem with the A2 sunset is that without A2s, there are some grants being funded that wouldn’t be if there were A2s, and some grants not being funded that would be.

So I ask this of those of you arguing strenuously for return of A2s: what is the nature of these grants that are being funded that shouldn’t be, and those grants that aren’t being funded that should be?

And to amplify: You *can’t* just tell us about grants that should have been funded that weren’t. You *also* have to tell us about grants that were funded but shouldn’t have been.

In hard times as well as good, people who get paid (funded) should be capable of making the three point shot consistently, hitting the home run when bases are loaded, hitting lots and lots of singles (like I did), bowling the perfect game, making an eagle, setting speed records, passing the touch down pass when you need it, scoring the goal, composing music that lasts centuries, doing science that makes it into the text books or leads to the next important drug or treatment. They could also be training the next cadre of scientists. Further, all this should be done with the utmost integrity.

We really do not need to be counting the number of papers or even citations, albeit these serve as a guide. There is a great time abyss that needs to be conquered with a 4-5 five year NIH grant award. A scientist’s work, funded by a grant or not, should last long after their career ends. The length of the grant should not last longer than the work so that there is a continuous need for refunding on an incremental project. Rest assured, the next brick in the wall will be laid by another good scientist, probably much more easily than you would imagine. Also, there should be no need to replace that brick that was already paid for.

If this can not be seen, the grant should not be funded.

Scientific career security can not be found in non-sustainable endeavors such as academic research without considerable talent, political savvy and salesmanship. (Remember this is the tournament model. One missed point or split-second matters.) Ultimately, research needs to sustain itself through practical application. Find sustainability for your work beyond NIH grant funding.

I know it would be impossible to know, but how likely is that the “thousands of senior well meaning investigators” who want the A2 back have A1s withint 5 to 10 percentile of current paylines ? I am going to say the vast majority of them.

Here’s the thing: I’m surprised and disturbed by the number of experienced scientists saying here that they are “insulted” by the data presented above. Data cannot be “insulting.” Data is data, and if it tells you something that you didn’t want to hear–well, that sucks but it’s the data. I understand that keeping our labs afloat is our number one emotionally stressful issue–as a pre-tenure assistant prof., I’m just as stressed out (as an aside, these difficult times are perhaps reminding you all firsthand of how it really has been for junior PIs in the last 10-15 years now that paylines are not at the 30-40% range like they were when you got tenure).

But are you all so married to your hypothesis that the A2 would be your golden ticket that any data to the contrary are “insulting?” Taking data personally, and dismissing an experiment as having something “wrong” with it just because it doesn’t tell you what you want to hear and validate your prediction, are examples of “Bad Science 101.” You are all so emotionally invested (because getting/losing funding is a life or death issue for all of us in this business) in needing to see your prediction borne out in your favor that you are trying to demonize the results of an analysis.

If you think the analysis was performed incorrectly, hey: rePORTER is available to all of us, feel free to repeat the experiment yourself. But step back and remove your personal feelings and bias from the analysis, and do not let what you WANT to see in the results cloud your judgment. (and to the person who claimed they say some fiddling of A2 vs. A0 status in a grant in rePORTER… seriously dude, take off your tinfoil hat.)